Tony Fernandez atop Windom Peak in the Needles Mountains. The author and his brother tempted fate by linking Windom, Sunlight Peak and Mt. Eolus in a one-day push as the weather slowly deteriorated, as often happens in the San Juans.

Have you been developing an urge to tackle one of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks? Yes? But then you read of multiple deaths on one peak in the past six weeks. Is it time to reconsider your ambition?

The author heads up-valley on a recent climb of Grizzly Peak southwest of Independence Pass. The appeal of Colorado’s high country is obvious but hazards abound. Experience gained over time is the climber’s best defense.

Be assured that if you spend enough time in the mountains, you’ll make a mistake: a dropped glove, wrong fork taken, water depleted, late start, disregard of deteriorating weather, stubborn insistence on completing the climb. The key to survival is breaking the chain of seemingly small mistakes that, in retrospect, seemed to lead inexorably to the incident.

Like the Mother Goose poem about the kingdom lost for want of a nail, an innocent decision made in haste or without consideration of alternatives can be the first in a series of incremental choices that can result in tragedy.

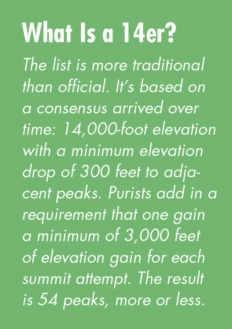

Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks present plenty of objective, or external hazards: steep terrain, rotten rock, exposure, route finding challenges, elevation, remoteness and so forth. But it’s how one deals with the conditions under one’s control that really matters.

Capitol is a serious peak requiring careful “scootching” across the Knife Edge. There is no “easier” route to this West Elks summit.

The recent spate of high country fatalities, including five on Capitol Peak alone, remind us that a proper approach to “subjective” or internal hazards is essential. Have I studied the route? Am I fit enough? Have I checked the weather reports? Is the climb within my technical abilities? Did I start early enough to beat the afternoon storms? Do I have a partner? Did I tell others where I went? Am I willing to turn around before the summit if conditions dictate?

I climbed Long’s Peak the week I moved to Colorado. Twenty-two years later, I reached the summit of Mount Wilson, completing my (initial) tour of Colorado’s 54 14ers. Along the way, I made plenty of my own mistakes, each of which was completely preventable:

Leaving trip planning to someone else, resulting in a treacherous un-roped traverse between Crestone Needle and Crestone Peak.

Staying high too long on three peaks, and finding myself in an electrified atmosphere with hair standing on end.

“Bagging” three peaks in one day (Ellingwood, Blanca, Little Bear) and forgetting to drink enough water in the headlong rush, resulting in a crushing headache and nausea.

The large majority of Colorado 14ers are relatively simple nontechnical “climbs.” And perhaps that’s where the biggest potential for problems arises. Because to do such a climb merely requires that you place one foot in front of the other. To start a 14ers climb, one simply begins to walk. It’s not like rock climbing or even scuba diving where you know by the context that you’ve entered a different world. Without a clear boundary defining your entry into a world of new hazards, you might not be aware that you’ve become “committed” (a climber’s term suggesting that things are getting serious) and those innocent decisions can add up to a significant, subjective hazard. But, as with scuba diving, a carefree, weightless sunny day can quickly turn dangerous. Running out of air 100 feet down or getting cliffed-out above tree line are terrifying but preventable situations.

Although I’ve climbed all the 14ers and a bunch of the high 13ers, it’s been done over the span of 47 years. That leisurely pace helped me learn along the way. It’s been more of a lifestyle than a tick-list. Here are some lessons learned and resources that have helped me:

Ease into it. Start low and slow. Colorado is full of attractive “sub-peaks” that will get you used to exercising sound judgment above tree line.

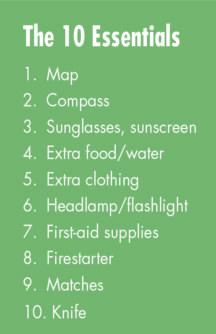

Carry the 10 essentials (see sidebar) and pair up with the 11th essential—a partner or better yet, two or three.

Find a mentor or consider getting some training. The Colorado Mountain Club offers a full range of classes and trips, from simple hikes to high-altitude mountaineering. Professional guide services are another option. Be wary of informal meet-up groups; ascertaining skill levels, experience and safety attitudes is a crapshoot.

Be humble. You’re not “conquering” anything. You’re there as a guest of the mountain gods. Be prepared to turn around when conditions turn adverse. The mountain will be there the next time you try.

Study the route ahead of time using one of the excellent guidebooks out there. Learn how to read contour maps as you develop your mountaineering sense.

This is a picture of what not to do: find yourself atop a 14er (here, Mt. Eolus) with your hair standing on end because of an electrically charged foggy atmosphere. The author and his brother Tony (pictured here) descended quickly but had to navigate the notorious “Sidewalk in the Sky” in wet, slippery conditions.

Have someone in the party carry a cell phone but don’t depend on it for navigation. You could lose service or simply run down your battery.

Be aware that altitude can affect anyone regardless of how fit. When I climbed 18,850-foot Pico Orizaba in Mexico, the printer from Loveland couldn’t proceed above 14,000 feet while the software guy from Minneapolis had no problem (he had trained by running up a 50-foot hill 50 times a day with a 50-pound pack). A recent death at Conundrum Hot Springs near Aspen might have been prevented if the 20-year-old hiker had descended upon showing symptoms of altitude sickness.

Lightning kills. Go down. Minimize the chance of thunderstorms by summiting early. The rule of thumb used to be, Descend by noon! It would be more prudent to start down by 11.

Give back to the mountains: leave no trace, pack it in and pack it out, stay on trails, contribute to your local alpine rescue group (e.g., purchase a Colorado Outdoor Recreation Search and Rescue [CORSAR] card), and volunteer with a group like the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative in their effort to minimize high country trail erosion.

And while we’re at it, it’s not all about peaks exceeding 14,000 feet. Colorado has hundreds of mountains in the 13,000-foot range. There, you can still find the solitude I enjoyed on 14ers 40 years ago. I hiked up 13,998-foot high Grizzly Peak last year with only my partner and some elk for company.

Guide Books

When I started, we were limited to Ormes’ Guide to the Colorado Mountains, good for its day but lacking basics like contour maps. My favorite is Jerry Roach’s Colorado Fourteeners: From Hikes to Climbs. It is especially helpful in outlining alternative routes that vary in “class” (technical difficulty) and “grade” (the overall difficulty including total length, elevation gain and level of commitment). With it, you can tailor a route to your skill level and tolerance for “exposure.” If you are interested in a thorough orientation to adventuring above tree line, the venerable Mountaineering: Freedom of the Hills by the Mountaineers of Seattle can’t be beat.

0 Comments