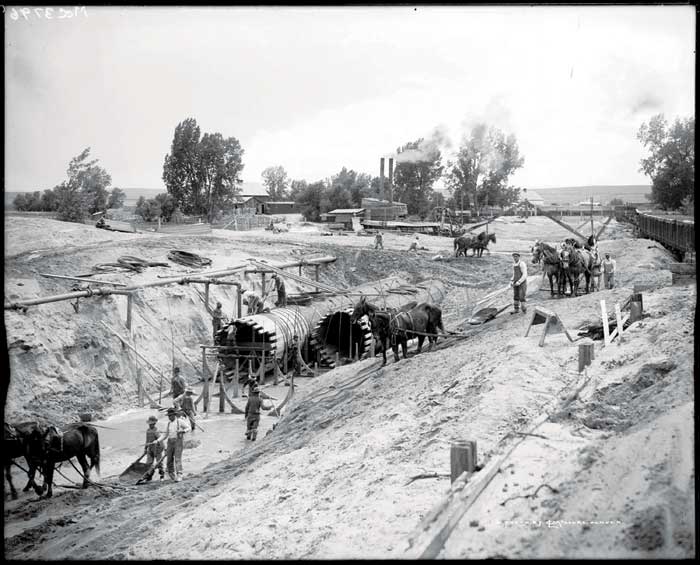

In the late 1800s, ditches that brought water to citizens were often contaminated by livestock feces and disease. Containment in wooden pipelines like this one, together with chlorination, helped address such problems.

What’s the story behind the water that comes out of our taps? Ever worry about how safe or expensive it is, or whether it’ll run out?

To address these issues, we need to know where our water comes from. Unless you’re drinking nonrenewable groundwater like citizens of Douglas County, the bulk of our water melts from Rocky Mountain snow. But most of this runoff flows westward, rather than eastward toward the Front Range where most Coloradans live. So we finagle it eastward by sucking it through a byzantine maze of tunnels, pipelines, reservoirs and canals. This diverted water joins up with the water collected from the eastern slope of the Rockies, often flowing downhill in existing streams and rivers. Municipalities from Fort Loveley (Fort Collins-Loveland-Greeley) to Pueblo capture, test, and clean this water, and then store it in manmade tanks where it awaits the tug of your faucet. Even in mountain burgs like Leadville, the story is the same.

So what’s there to be concerned about? Colorado is growing. A lot. Which means more baths, more grass, and more crops that need water. Yet the runoff-capturing system of the Rockies is nearly all spoken for. In some years, there is a bit of water left untapped in the system, but in many drought years there is not enough because less rain and snow falls.

Sometimes heavy floods, like those of last September, help the system catch up, by filling reservoirs that buffer demand. But multiple dry years or less-than-average snowpack years, coupled with steady population growth, means that the system is at its tipping point.

The days of prospecting for more Rocky Mountain water are essentially over. Thus viable solutions include conservation or “buy and dry”—a strategy employed by cities like Aurora where water is taken from farmland and used to slake suburbs.

In terms of conservation, there are some efficiencies to be gained within our water distribution system, including reducing water losses due to evaporation from canals and reservoirs and from fixing leaking pipelines and tunnels. But these losses, generally 5–10 percent of the distributed water, are not sizeable enough to satisfy future demand.

Fortunately there are many opportunities to improve our individual water usage efficiency. This is illustrated by the great variation in the amount of water used by like-kind individuals in the Front Range. For example, over the course of a year, Denverites use about 85 gals/day on average whereas those in the Springs use almost 100 and Fort Loveley residents use about 140. Yet in the same cities, many folks who have similar homes and needs use much less water. See http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/consumer/09952.html for some ideas about upping your water game.

In the quest for more water, is safety being compromised? Back in the day, Colorado settlers would drop a silver dollar into a water barrel to keep it pure. We’ve come a long way since then, but we still leverage the antibacterial properties of silver and other materials to purify water. This is important because mountain meltwater passes through squirrel scat, mine dumps, and all sorts of soils en route to drinking water reservoirs. Water agencies test and clean the heck out of these waters, and despite the myriad pathways by which water is diverted to our towns and cities, they uniformly deliver safe water. At the same time they boost the water’s natural fluoride levels by a tiny amount, to reach recommended levels. Some have even begun monitoring for pharmaceutical derivatives in the water. Although they’re not yet at high-enough concentrations to be of concern, such substances are increasingly found in drinking and irrigation water.

Pumping, cleaning, and maintaining our water consumes a huge amount of energy. And this costs money. How much, though? To put things into perspective, our family uses between 5,000 gallons (gals) per month in the winter and 10,000 gals/month in the summer. Like many mountain communities we pay as little as $2.58 per 1,000 gals. In contrast, other Front Range communities pay a lot more—$4 to $5 per 1,000 gals. It could be worse, though. Los Angeles residents, who divert mountain and agricultural water just like we do, pay more than double our cost—$6.31 per 1,000 gals. And their water tastes like a swimming pool.

So as we look to the future, perhaps we ought to think about water in the context of energy and public health. And, with an eye toward balancing economic and population growth with needs for water for farming, forests, wildlife, recreation, and tourism. The water coming out of your tap impacts all these arenas.

In the meantime, I’m looking forward to turning on our outside spigots so our kiddos can frolic on our Slip’N Slide. To offset this fun and frivolous use of water, maybe I should skip a few showers this summer.

James W. Hagadorn, Ph.D., is a scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Suggestions and comments are welcome at jwhagadorn@dmns.org.

Beginning May 1, Denver Water is implementing watering rules. Do you know the rules? Read here for details.

0 Comments