Chocolate from Stapleton Front Porch on Vimeo.

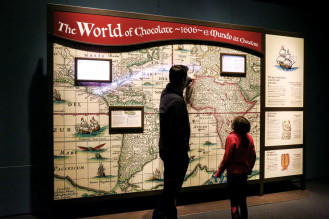

A world map shows the early trade routes for cacao. When the Spaniards defeated the Aztecs, they found not gold but cacao, which became popular throughout Europe.

“Chocolate has a 10-million-year evolutionary history and has been cultivated by humans for 6,000 years,” says Chip Colwell, curator at Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “The Mayans and the Aztecs believed it was a drink of the gods. They even believed humans were made from cacao.”

By the 1400s cacao was a key element in trade among the Aztec people in Mesoamerica (much of central America). It was used as a luxury drink, as money, as an offering to the gods, and as payment to rulers. In the Aztec world cacao seeds were worth a fortune.

But the benefits cacao brought to the Aztecs ended suddenly when they were conquered by Spaniards in the early 1500s.

A panel of murals shows the dark underside of the early cacao industry. After the Spaniards conquered the Aztecs, they set up a system of forced labor to work the land the Spaniards controlled.

A museum volunteer shows a decorative pot used for frothing cocoa. The Mayans blew into the tail to create froth.

In 1519 Hernán Cortés led Spanish soldiers to the Aztec capital in search of golden treasures. Instead they found storerooms packed with valuable cacao seeds. In 1521 Spain defeated the Aztec—changing their way of life forever. Spanish soldiers demanded Aztec nobles hand over their treasures or be killed and they enslaved the Aztec people to produce the cacao they shipped to Europe. Many Aztecs also fell victim to diseases the Europeans brought with them to the Americas.

After the Spanish introduced cacao to Europe, it wasn’t long before sugar was added—and sweetened chocolate quickly spread throughout Europe as a drink of the wealthy classes. The Spaniards invented the molinillo, a stirrer to make the cocoa frothy—and stirrers for the same purpose are still used today. “Here we are thousands of years later drinking chocolate the same way. It connects us today to people living thousands of years ago,” says Colwell. Museum visitors can view wooden stirrers designed by the Spaniards as well as the modern day equivalent.

A museum volunteer shows a decorative pot used for frothing cocoa. The Mayans blew into the tail to create froth.

The growing popularity of sweetened chocolate, coffee and tea in Europe increased the demand for sugar, which, in turn, increased the number of enslaved people during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The museum exhibit offers a simple and grim explanation of how this increased demand for cacao, sugar and other crops was met. The production of cacao in southern Mexico and Central America “depended upon local laborers, until the Native population was drastically reduced by the spread of European diseases. To replace this Native labor force and continue cultivating crops, with sugar being one of the foremost, many colonial landowners relied upon the system of African slavery established by European and Arab merchants … A combination of millions of wage laborers and enslaved peoples were used to create this workforce.”

As the chocolate industry grew over the years, manufacturers developed distinctive packaging to market to a mass audience of consumers.

Although slavery was abolished in all countries by 1888, the need for labor to meet the demand for products like sugar and cacao continued. In some tropical countries harsh labor conditions prevailed long after the end of slavery. However some activists in the world of chocolate spoke up to change these conditions and in 1910 the U.S. banned cocoa that was the product of plantations using slave labor.

However, even today, with 40 million people working in the chocolate industry, most chocolate is still grown on family farms and harvested by hand. Almost half of the world’s supply is grown in the Ivory Coast in West Africa. Cacao pods are cut from the tree with a machete or small blade and gathered in net bags.

The farmers split the pods, revealing white pulp that encases the cacao seeds. This pulp containing the cacao seeds is left in boxes (or baskets or under banana leaves) for about a week to undergo a fermentation process that changes the flavor and the purplish seeds turn to a rich dark brown. The cacao seeds are then shipped to factories that produce cocoa powder, cocoa butter and chocolate.

Despite international programs to investigate and reduce child labor, the effectiveness of these programs has been limited. Because of the complexities of cacao trade on the world market, it is almost impossible to identify which cocoa was or was not produced with child labor. More needs to be done to remedy the situation.

Information in this article was taken from Chocolate: The Exhibition at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. It will be open until May 8, 2016.

The chocolate exhibit ends with a personality quiz that identifies visitors’ “chocolate personality” (milk chocolate, dark chocolate or white chocolate) based on their answers.

0 Comments