Colorado birthed a revolutionary health advance that impacts societies worldwide. And it happened by accident, owing to a newbie dentist’s curiosity, and some funky water that dribbled off Pikes Peak.

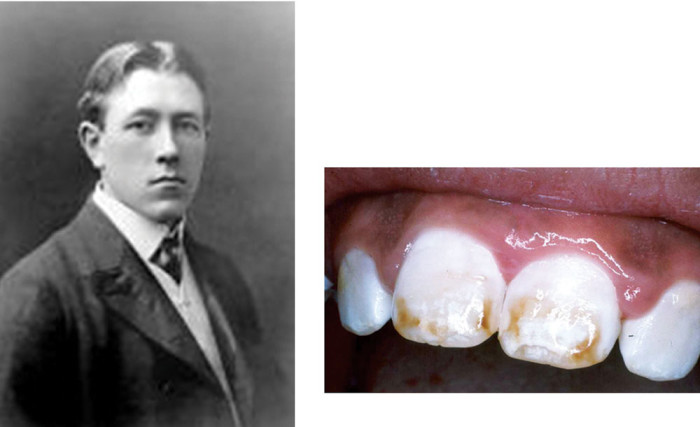

Over a century ago, Dr. Frederick McKay got off the train and hung his shingle in the bustling burg of Colorado Springs. He was soon shocked by the abundance of chocolate-colored and disfigured teeth among his patients. Nothing like this had been reported in his training, in part because it is rare. He fittingly dubbed the condition Colorado Brown Stain.

Over a hundred years ago, Dr. Frederick McKay’s curiosity about the cause of brown stains on teeth led to the discovery that excessive fluoride in the water in Colorado Springs was causing the stain.

Over a hundred years ago, Dr. Frederick McKay’s curiosity about the cause of brown stains on teeth led to the discovery that excessive fluoride in the water in Colorado Springs was causing the stain—and also that patients with stained teeth hardly had any cavities.

Because teeth are made of minerals grown and maintained by our bodies, McKay reasoned it must be something in his patients’ diets that caused the stain. Yet it took 30 years of sleuthing before his colleagues figured out the root of the condition. Turns out the well-water and stream-water his patients drank was super-enriched in fluoride. This excess fluoride was causing teeth to become disfigured prior to emerging from the gumline of children of the Springs. The fluoride came from the breakdown of fluorine-bearing minerals in the rocks and soils that lined watersheds near Pikes Peak.

But more important than solving the mystery of Colorado’s Brown Stain, McKay noticed that patients with stained teeth hardly had any cavities, and thus were able to avoid getting teeth yanked as they aged. It was this observation that forever changed the game of tooth care—because it established the first link between fluoride and protection from tooth decay.

Today we know that low levels of fluoride in water, whether added by people or Mother Nature, helps the outer layer of our teeth, or enamel, in three ways. The presence of fluoride in water and saliva facilitates remineralization of our teeth’s apatite enamel when it’s etched by the acids produced by our mouth’s bacteria—the same everyday microorganisms that are found in plaque. Secondly, the same fluoride inhibits the ability of these bacteria to produce tooth-etching acids. That’s why fluoride is also added to toothpaste, because a bedtime brushing leaves a residue of fluoride in your mouth overnight to battle these cavity creeps. Finally, when babies and kids grow up drinking water with low levels of fluoride, the fluoride compounds in their body’s tooth-building tissues cause them to grow teeth whose enamel is more structurally sound, and whose crevices are less cavity-prone.

Since McKay’s early days of scientific discovery, fluoride has widely been added to toothpaste and drinking water worldwide. Fluoridation of our municipal drinking water has drastically reduced national rates of dental cavities, extractions and the like, while simultaneously improving overall school and workplace attendance and productivity. Even more amazing, these advances have happened despite the increase of sugary beverages and sugar- and starch-rich foods in our diets, which are the prime food for the plaque-spewing bacteria that lurk in our mouths.

Fluoridation also saves money. For every $1 invested in fluoridation per year, about $20–60 per person is saved annually in lifetime dental costs. I wish my retirement fund had returns like that!

Fluoridated water is pervasive in your diet—even in products made with it. It’s in your beer, your whiskey, your soft drinks, and even in those sport beverages. Not that you should rinse with these before bedtime, mind you.

Although the vast majority of scientists believe fluoride is safe and beneficial, some members of the public continue to question it’s safety. Photo from FluorideAlert.com

Should we worry about fluoride? No. Despite the occasional scary-sounding warnings presented by a handful of PhD-toting outliers, there are no major health risks from drinking municipally fluoridated water. Nor are there risks from using toothpaste and the like, unless you’re letting your kiddos gobble it.

Fluoride is one of many naturally occurring substances that are added to our diet in tiny amounts. Consider iodine in salt, vitamin D in milk, or folic acid in cereals. These compounds have helped to abate tragic conditions that used to be commonplace—like goiter, rickets, and spinal bifida.

And the Colorado Brown Stain, for which we were nationally known? It has all but disappeared, too—because scientists figured out how much fluoride is helpful, and how to get rid of it when there’s too much in the water.

What’s the next major breakthrough in dental care? It might come from within our very own mouths. That’s because genetic mapping of the ecosystem of microorganisms in our mouths is now an accomplishable reality. As we’ve learned with our gut bacteria, differences in these ecosystems from one individual to another may explain why some of us are more prone to cavities, gum disease, or infection than others. Who knows, maybe the next big dental discovery will again be made in Colorado.

James Hagadorn, Ph.D., is a scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Suggestions and comments are welcome at jwhagadorn@dmns.org.

Hi James: This was a timely article for my family. My father was raised in Colorado Springs and did have the brown stains on his teeth. We knew that the stain was the result of fluoride in the water, but did not have the full report that you have in your article.

Thanks,

Richard Crabb

Richard: Whew! I have a cousin who also has the stains… in part because her mom gave her fluoride tablets and they also drank fluoridated water… so in that case a bit too much was added to her system. But… she has no cavities. Best regards, James