Mayor John Hickenlooper (left) and Mayor Wellington Webb (right), hold the Green Book (Stapleton’s Development Plan), with Sam Gary at 29th Ave and Valentia St. in Stapleton. S

April 2010 Front Porch

“We are building a ‘city within our city’ that we hope will set an impressive standard for smart growth in Colorado and in the nation.” —Mayor Wellington Webb

To piece together the story of how the Stapleton we know today came to be, the Front Porch interviewed the people who were a part of the historic events that brought us to where we are today.

One might think of Denver’s vote to move the airport as the crucial moment that made the Stapleton neighborhood happen. But, as we learned from former mayor Federico Peña, there were many hurdles to be crossed before the question of a new airport came to the voters.

Mayor Federico Peña

“Denver had to annex 50 square miles from Adams County for DIA, and that required a full

The May 17, 1989 cover of the Denver Post featured Mayor Federico Peña and Governor Roy Romer at the downtown victory celebration the night before.

vote of Adams County. The formal negotiations with Adams County were closed to the public—I got a lot of heat for it,

but it was the only way we would come up with a resolution,” says Peña. Adams County wanted a commitment that Stapleton would be closed as an airport and it would not be used for any kind of aviation use. “So the quid pro quo was a whole lot of stuff – 50 square miles of land, all of the other political support they were going to give us in getting those elections passed in Adams County. That’s sort of how this first started to emerge as a possibility.

“The physical and legal annexation of 50 square miles of land to Denver expanded the size of the city and county of Denver from about 110 square miles of land to over 150 square miles of land. So the city grew by a third with that annexation, which people today, I think, find a little unbelievable.

“In about 1988 or so, I created something called the Stapleton Tomorrow group that included business leaders and civic leaders and neighborhood activists and citizens. The purpose of the group was to think very broadly about what the future of Stapleton might be. It was not a development plan, it was simply a list of desires, aspirations in a diagram of what people wanted or could foresee in the redevelopment of Stapleton in the future.”

“People were focused on could the city sell the bonds, could the city get $500 million from the FAA, could the city break ground. So there was very little broad public attention on redeveloping Stapleton. At least that is my recollection. But for the people who were thinking about how to redevelop Stapleton there were lots of different ideas.”

Peña continues, “Some people said, let’s just sell it all—do a bulk sale of all the land, maximize the profit because it was probably more valuable as a whole than to cut it up into parcels. Some people wanted the city to run it—at least the airport staff to run it and figure out how to sell the land and redevelop it.

“We had a team of people, citizens in Denver, most of whom shared the vision of being a better city, imagining a great city, who were not satisfied with the pace of change in our city back then. I give credit to the people of Denver and Adams County who shared that dream,” says Peña.

Sam Gary, Founder of The Piton Foundation

The three mayors we interviewed all talked about one key person who kept the planning on track for the kind of “new urbanism” community we see today, and that person was Sam Gary.

Mayor Peña said, “Sam was the key, he was the one who was willing to fund the early planning and the strategic thinking. Without Sam G’s support we would not have been able to pull this off. The city was broke… He was a visionary leader.”

From the May 2000 Front Porch—“On the day Stapleton closed in February 1995, the airport listed approximately 4.5 million square feet of building space spread over nearly 150 structures on the property’s 4,700 acres. Half of that space was accounted for by the terminal and its five concourses. Those concourses were removed more than a year ago and the demolition of the terminal itself is well

on its way to completion.” (photo below)

Mayor Webb said, “Sam Gary, to his credit, put together a citizens advisory group and created the Green Book (the development plan for Stapleton) with citizen input.”

And Mayor Hickenlooper said, “The key to the development of Stapleton exemplifies the importance of civic leadership… the role Sam Gary of the Piton Foundation played.”

Sam Gary is the co-owner of the Gary-Williams oil company and is the founder of the Piton Foundation, which has as it’s mission to create opportunities for families and children in Denver to move from poverty and dependence to self-reliance.

Not long before the vote to relocate the airport, Sam Gary had met James Rouse whose company built the planned community of Columbia, Maryland, which was based on many of the ideas that were later written into Stapleton’s Green Book. Gary was interested in “new urbanism” and wanted to become more educated on the subject, so he and his wife invited Rouse to spend a weekend with them in Montana. “He was way ahead of anything I’d ever thought of. Jim Rouse was a visionary. He had made a huge impact on urban renewal,” says Gary.

Tom Gleason (who at that time was Mayor Peña’s press secretary) remembers the day Peña announced that the city was going to undertake the development of a new airport. “One person in the audience of business leaders immediately asked himself, ‘I wonder what they’re going to do with the old airport.’ And that person was Sam Gary,” says Gleason. “That’s the moment when Sam Gary began to bring together business leaders to create a development plan.”

Summer 2000—“The (demolition) work is being funded by Denver’s Department of Aviation (which owns the land until it is sold to Forest City Stapleton). The work is being done by contractors selected under the City’s bid process and supervised by the Denver Department of Public Works.”

Gary’s mission was “to break the pattern of urban sprawl.” “You say that to most people at that point in time and they’d take off at a rapid pace. It seemed to me that it was a huge opportunity,” says Gary.

“He wanted to be sure some greedy developer didn’t come along and buy this cheap and flip it and let it go into blight. He wanted it to be a vibrant community and one where the existing communities weren’t left behind,” says Bev Haddon (now CEO of the Stapleton Foundation), who was recruited by Gary to participate in the development plan.

Gary says, “So we just started talking. It was conversation. I had some money I could put into it, and then others put some in.” Bev Haddon describes how Gary formed a “kitchen cabinet” of business people who had shown a commitment to the community. The group raised $4 million to create the master plan and Gary-Williams gave over 50% of that $4 million. “But we finally got every big business and foundation to contribute to this effort, and it was pretty much the first time they had ever contributed to an economic development activity rather than to social services. We were saying that if you can create a community that will bring in other communities, that will do more than what the social services can do,” says Haddon.

“This group was pretty diligent about meeting. You know, groups have a way of thinning out pretty quickly, but this group was pretty passionate about what they were doing,” adds Gary.

Mayor Wellington Webb

In 1991, when Wellington Webb came into office as mayor, “the big issue for us was construction and the building of Denver International Airport,” says Webb.

But, says Bev Haddon, “He told us, ‘Work with my people.’” Sam Gary recalls that Jennifer Moulton, Denver’s City Planner under Webb, was a very active advocate for what the planning group was doing. And Webb points out that one of his priorities was to have more citizens from the local community added to the planning process.

Webb, though occupied with the airport, said he was also fending off the other proposals being made for the Stapleton site. “Some people felt that the Stapleton land, because it was an old airport, had zero value because of the amount of cleanup that was going to be required… At that time Denver had lost population. So the other emphasis was to change the initial thoughts on Stapleton from being a residential community to using it as an economic generator for the city.

“Continental Airlines was looking for an airport maintenance facility and the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce was pushing to place that airport maintenance facility at Stapleton. So part of our effort at that time was to continue planning what kind of neighborhood we wanted to build at Stapleton, and at the same time to repel efforts by those who wanted to do what we considered to be shortsighted.”

Webb continues, “The next issue to come up that we had to repel was that there was strong interest by many to build a new football stadium at Stapleton. My goal was twofold: I wanted to drive all of our sports and cultural amenities downtown for the purpose of giving people a reason to move back to Denver and to preserve the Stapleton project as a residential community.”

Bev Haddon says the planning group continued working together until 1995, when, with Mayor Webb’s support they took the plan before the City Council, “and it passed 13 to zip. Over 250 people were in the council chambers to testify in favor, and not one testified against it.”

In the midst of all the airport construction issues, Webb had another big item on his agenda—who was going to be selected as the master developer. “After long, drawn-out negotiations, Forest City was selected… we made people stay in the room until the deal got done… (but) there were some aspects of the negotiations that just about broke down. The first area was on the amount of park space. What I told Jennifer Moulton was that because I’m a parks person, we’re going to develop the parks system first, then we’ll develop the neighborhoods around it. Because if you don’t build the parks in the first place there won’t be any parks to build. That just about cratered the deal because of the insistence of the city in terms of the amount of parks they had to build… I think a lot of people just took for granted that there was this Green Book and all of a sudden it just happened—and that’s not the case.”

The Demolition

May 2000—“Recycled Materials, Inc., an Arvada company, removed approximately 1000 acres of the former airport pavement at no cost to the City of Denver in exchange for the right to sell that material on the recycled market.”

Clearly there were many bumps along the road, but in Mayor Webb’s words, “I think if people of goodwill are out to make something positive happen, the negotiations are really around the edges… We picked Forest City based upon their track record… they were also the most flexible in terms of meeting the city’s goals.”

Ronald Ratner, President/CEO, Forest City Residential Group

Ronald Ratner, says that Forest City had heard about the Stapleton project and, as part of another trip, he stopped in Denver for what was scheduled to be a brief morning meeting with Dick Anderson, Director of the Stapleton Development Corporation. That meeting turned into the entire afternoon and evening. “What we were saying and what he was saying were literally so parallel… Forest City was, to some extent, a six-fingered glove for a six-fingered hand. The city really wanted to get good value for the land but wanted to create long-term a great asset, a great neighborhood.

“We had done a lot of large-scale mixed use, but with urban infill at the time 10 acres, 25 acres—50 acres would be huge. The idea of an urban infill project that was 4,200 acres was then and is now really unheard of… We did a lot of homework to understand the transaction and made an offer. The city then decided it couldn’t accept a sole source offer so they put out a formal bid process.”

Ratner says Forest City has viewed working with the Green Book as a tremendous advantage. “It was exactly what you wanted… a framework document with very strong principals that say, ‘This is what we want to do.’ …At one point I asked council president Happy Haynes how she viewed the Green Book. She said, ‘Young man, on my night stand I have my Bible and my Green Book and I’m not sure, if there was a fire, which one I’d grab first.’” Ratner concludes by saying, “In 35 years of doing business there’s nothing I’m prouder of.”

Summer 2000 demolition of the old Stapleton airport concourse.

Mayor John Hickenlooper

When Mayor Hickenlooper came to office in 2003 Stapleton was just starting to look like a community… still a lot of dirt fields, but the vision was, by then, becoming a reality. He describes Stapleton today as, “a national model for urban infill and it has fulfilled almost every expectation… the infrastructure, the parks, even without big trees it’s beautiful, although building schools has been more challenging.”

The Mayor goes on to say, “The biggest question from other mayors is they’ve been curious about how it was planned and what is the city’s relationship with the builders.”

If those mayors knew the whole story, they would wonder how Denver was so fortunate as to have the combination of visionaries and committed citizens that was required to turn an old airport into a thriving mixed-use community.

From the Green Book—Stapleton will be a unique mixed-use community capable of supporting more than 30,000 jobs and 25,000 residents. More than one third of the property will be managed for parks, recreation and open space.

Summer 2000—Forest City will go through extensive review processes with the city… and there’s a whole crowd of citizens out there who have practically memorized the “Green Book.” –Jennifer Moulton, Denver’s City Planner

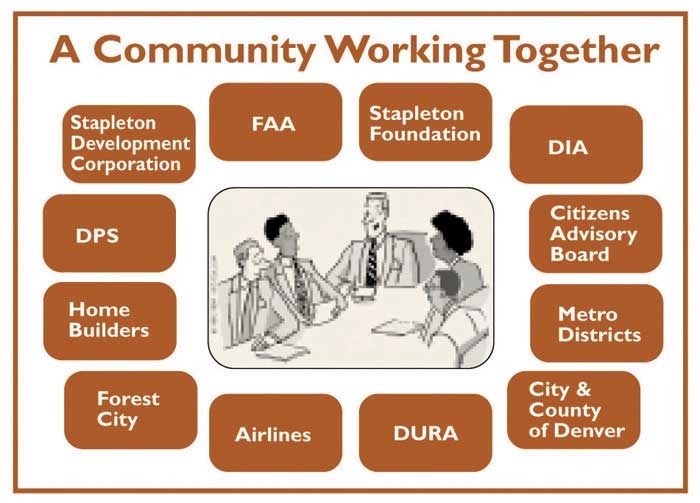

A diagram of the process to build Stapleton.

May 2000— “Instead of selling individual parcels and waiting to see what kind of development we end up with, we worked with the community to develop a master plan and select a master developer… that would develop Stapleton based on an integrated and wholistic vision.”

–Jennifer Moulton

Early construction of Stapleton.

Quebec Square: Opened Summer 2002

First home: Occupied July

2002

Town Center: Opened Summer 2003

First School: Opened Fall 2003

The Infrastructure

May 2000—Editorial from the Feb. 16, 2000 Denver Post: “The most difficult issue of all may have been how to pay for the massive public infrastructure… most of the actual on-site infrastructure improvements will be paid for initially by the master developer…it means the developer assumes the primary financial risk for making the project succeed. In short, if the redevelopment flops, …Forest City would have to eat its losses.

The ultimate test of the ‘new urbanism,’ after all, is to prove that high-quality urban villages such as planned for Stapleton can actually compete economically with far-flung exurban developments.”

0 Comments