As a young man, Ed Dwight was on track to become the nation’s first Black astronaut. When that attempt was thwarted, he pivoted and eventually became a sculptor. His Park Hill studio is filled with just a fraction of the 18,000 gallery pieces he’s created. Dwight is famous for using “negative space” in his sculpture, as seen in the Louis Armstrong sculpture in the foreground.

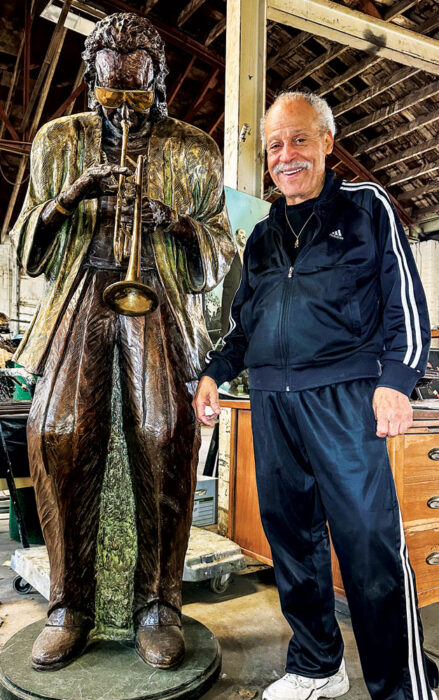

Sculptor Ed Dwight, in his North Park Hill studio, stands next to his rendering of Miles Davis.

For more than four decades, Park Hill resident and sculptor Ed Dwight has been casting Black history-makers in bronze to ensure that future generations know about their contributions to society. Sixty years ago, Dwight himself was on a path to make history as the nation’s first Black astronaut, and although that didn’t happen, Dwight has been a history-maker in his own right throughout his 89 years of life.

Born in Kansas City, Dwight says he was interested in both art and airplanes as a child. “My mom was very aggressive about my learning. I got a library card when I was 4, and I would check out books about the great masters and try to copy the oil paintings and I would also study books about the science of flight.” While still in high school, he told his father that he wanted to study art at college. “And my father said ‘you’re going to be an engineer.’ When I said I didn’t know what engineers did, he said ‘all you need to know is they make money.’”

Dwight was studying architectural engineering at a local community college and holding down two newspaper delivery jobs when he read a headline about a Black pilot who had been shot down and taken as a prisoner in the Korean War. Dwight said that was like a light bulb going off: He hadn’t known that African Americans were allowed to fly planes. He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, got promoted through the ranks, and became a test pilot while also earning a college degree in aeronautical engineering at Arizona State University.

In addition to sculpting famous African Americans, Dwight wants to preserve the history of ordinary Black people, like these sharecroppers.

In the midst of the civil rights movement, Dwight says President John F. Kennedy was eager to find and promote a Black astronaut who could serve as a national hero, which is why he says he was picked to enter the astronaut training program run by Chuck Yeager at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Dwight soon appeared on Jet and Ebony Magazine covers. “I was traveling the country giving speeches and meeting with members of Congress.” Unfortunately, Dwight says he faced racism and hostility at NASA, and although he advanced through the training, he was not selected to be an astronaut. After Kennedy was assassinated, Dwight knew he didn’t have a future with NASA and he left the military.

He then held a variety of jobs: consulting for an aviation business, working for IBM, opening several restaurants in Denver, and dabbling in commercial real estate. Throughout all of those ventures, Dwight says he couldn’t ignore the desire to make art. He began by making small sculptures using found pieces of metal. Eventually, his sculptures attracted the attention of Colorado Lt. Governor George Brown, who was the first Black lieutenant governor in the country. Brown asked Dwight to create a statue for the Colorado State Capitol and encouraged him to begin a career as an artist who showcased Black history. “He told me that although Black people had been on American soil for 300 years, you would never know it by looking at all of the sculptures in public spaces. He said I could change that.”

Dwight documents Black history as far back as the 1500s and the beginning of the slave trade.

Since then, Dwight has been on a mission to do just that. At age 43, Dwight went back to school, earning an MFA in sculpture at the University of Denver and then receiving a commission from the Colorado Centennial Commission to create a series of 50 bronze sculptures that depicted Black pioneers, explorers, trappers, farmers, and soldiers who helped settle the West. Dwight followed that project with a series about the evolution of jazz—from its African roots to contemporary music. It consists of 70 statues, including depictions of Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke Ellington.

He’s also created a Rosa Parks sculpture in Grand Rapids, Michigan, a Medgar Evers memorial in Mississippi, and an Underground Railroad memorial in New Jersey. One of his largest projects is his Texas African American History Memorial in Austin. It portrays African American history from the 1500s to the present day and includes a depiction of Juneteenth when African Americans were emancipated. In Denver, Dwight’s most visited sculpture is the Martin Luther King Jr. statue in City Park. In all, Dwight says he’s created more than 130 memorial sculptures and over 18,000 gallery pieces.

Dwight’s studio and foundry are located in a 30,000-square-foot warehouse in North Park Hill. He oversees several artisan craftsmen to complete the large installations. Dwight, who is now legally blind, has begun to refer commissions to other artists because of his deteriorating vision. Still, he maintains a sense of humor and optimism when talking about his life. He credits his mother for his determination to push forward even against long odds. “Every night the last words I heard from her were: ‘There’s nothing on earth you can’t do.’”

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

“The Ballerina” is one of Dwight’s early sculptures using found metal pieces.

The Martin Luther King Jr. memorial in City Park is Dwight’s most famous work in Denver.

0 Comments