Bella Smith, a junior at DSST, questions the validity of lockdown drills. She finds it confusing that sometimes teachers know about fire drills beforehand but not lockdown drills. She said not knowing if the drills are real contributes to student stress, which is essentially hindering and not helping the problem. Event host Tricia Chinn Campbell (left) listens as Smith shares her concerns.

Annette Haugh was just seventeen when two bad guys with guns changed her life forever. “I separated myself into two parts that day—Columbine survivor and Annette—and I’ve spent the last twenty years trying to put those parts back together.” But it’s not just survivors who have to put the pieces back together; Annette wants people to understand that gun violence leaves a large wake. “There’s a ripple effect,” she says. “We’re all changed; we’re all living in a post-Columbine world.”

Annette Haugh was just seventeen when two bad guys with guns changed her life forever. “I separated myself into two parts that day—Columbine survivor and Annette—and I’ve spent the last twenty years trying to put those parts back together.” But it’s not just survivors who have to put the pieces back together; Annette wants people to understand that gun violence leaves a large wake. “There’s a ripple effect,” she says. “We’re all changed; we’re all living in a post-Columbine world.”

Those ripples of concern reached Stapleton in early September as two meetings addressing school safety were held in just one week. While the meetings addressed an array of issues including suicide prevention, safe gun storage, issues with Safe2Tell, and lack of proper access to mental health resources, no topic drew as much fervor as the lockdown drills recently conducted by DPS.

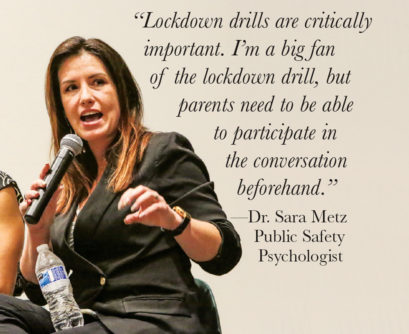

A central question of both meetings quickly became: Does the trauma of the lockdown drill outweigh the potential threat?

A central question of both meetings quickly became: Does the trauma of the lockdown drill outweigh the potential threat?

DPS Commander of Emergency Management Melissa Craven said DPS has beendoing lockdown drills since before Columbine, and they are not the result of an active shooter alone. “We locked down a building this week because of a high speed chase.” She also said they do not give parents the opportunity to opt their kids out of drills nor do they even tell the principal exactly when a drill will occur.

The mother of a Bill Roberts student, said, “I’ve been shocked by the lack of preparation around these drills. My six-year-old was sobbing at the dinner table because she was in the bathroom when the alarm went off, and she didn’t know what to do; she’s completely undone. This is not helping. The whole point is to make kids feel like there’s a sense of safety and control, so there need to be parameters; there needs to be communication.”

Annette’s husband, Ryan Haugh, echoed that concern. “Aren’t we just normalizing school shootings? Why are bullet-proof backpacks, lockdown drills, and specially-designed schools with wavy hallways and partial walls you can hide behind the price of going to school in this country? Isn’t that appalling?”

Annette’s husband, Ryan Haugh, echoed that concern. “Aren’t we just normalizing school shootings? Why are bullet-proof backpacks, lockdown drills, and specially-designed schools with wavy hallways and partial walls you can hide behind the price of going to school in this country? Isn’t that appalling?”

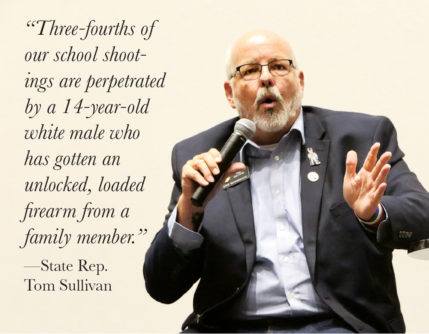

Representative Tom SulIivan, whose son Alex was killed in the Aurora theater shooting, said, “Of course that’s appalling, but our kids have come to the realization that it’s not an if but a when. It’s coming to your church, it’s coming to your theaters, it’s coming to your malls, and it’s coming to your schools, so the question is, what are you prepared to do about it? If you just want to shake your head and feel bad for the family it affected, then do nothing. But if you are concerned then you need to stand up and never sit down again. We as a community can stand up and do something about it.” Sullivan did just that last session when he drafted the Red Flag Bill, which is now Colorado law.

The state legislature’s school safety interim committee, which is bipartisan, is also standing up. They will met on September 20 to discuss which bills to draft for the upcoming session.

The state legislature’s school safety interim committee, which is bipartisan, is also standing up. They will met on September 20 to discuss which bills to draft for the upcoming session.

Moms Demand Action is also focusing on legislation including: universal background checks, child access laws that would raise the age to purchase a semiautomatic weapon to 21, and holding the gun owners responsible for a tragedy perpetrated by a minor using their weapon.

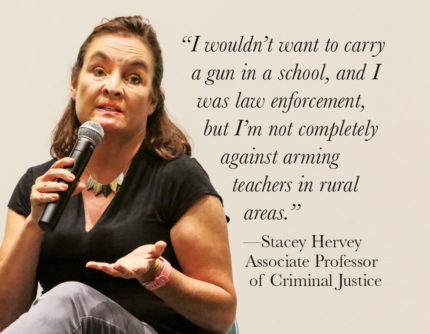

Conservative voices—which usually argue new gun legislation will only hurt law-abiding citizens and that the best defense for a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun—were either silent or absent at both meetings. In fact, one of the only dissenting opinions was given by Stacey Hervey, Associate Professor of Criminal Justice, who said, “I worry about our friends on the Eastern slope where first responders are sometimes twenty minutes away. I think if someone went through extensive training to carry a gun in that school, I would not be opposed.”

It’s been twenty years since Annette Haugh hid in a closet at Columbine High School and hoped for the best. Today she’s asking people to do more than hide and hope. She’s urging them to have open, honest, albeit potentially difficult conversations about gun violence. In a culture that’s quick to unfriend someone with an opposing view, Haugh encourages us to embrace one another. “I wish we lived in a world without guns, but I can understand why someone who’s been the victim of a violent crime wants to carry. We have to understand each other’s perspectives. Whether you’re pro or anti-gun, at our core—we’re all the same—we just want to feel safe.”

It’s been twenty years since Annette Haugh hid in a closet at Columbine High School and hoped for the best. Today she’s asking people to do more than hide and hope. She’s urging them to have open, honest, albeit potentially difficult conversations about gun violence. In a culture that’s quick to unfriend someone with an opposing view, Haugh encourages us to embrace one another. “I wish we lived in a world without guns, but I can understand why someone who’s been the victim of a violent crime wants to carry. We have to understand each other’s perspectives. Whether you’re pro or anti-gun, at our core—we’re all the same—we just want to feel safe.”

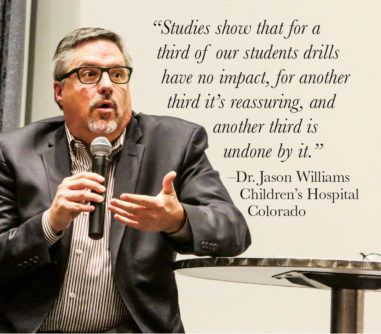

In addition to Haugh, Sullivan, and Hervey, Dr. Jason Williams, Children’s Hospital Colorado, and Dr. Sara Metz, a Public Safety Psychologist were panelists at the September 10 meeting. The event, held at The Cube in North Stapleton, was hosted by Tricia Chinn Campbell of Mom’s Night Out Productions (campbell@momsnightoutproductions.com).

At the September 12 meeting of Parents for Safe Schools, speakers were Abbey Winter, Colorado Chapter Leader for Mom’s Demand Action; Aaron Carpenter, Colorado Legislative Council; and Melissa Craven from DPS. The event was held at the Sam Gary Library and hosted by Rachel Baumel (rkbaumel@yahoo.com) and Dan Mitzner.

What students are saying

By Madeline Seibel Dean

Interviews with local high school students reveal a desire to have a voice in what policies are put in place to protect them. Students “definitely have not been involved enough” in gun violence issues, says Jonah Landeck, a senior at DSST: Montview. Griffin Moore, a sophomore at Northfield High School (NHS) who helped organize the walkout over school shootings when he was a student at McAuliffe, says “Letting kids have their voice and letting students have their voice, specifically for issues like this, [is needed] because we are in it, we are the students, not them.” Elliot Guinness, also an NHS sophomore who organized the walkout while at McAuliffe, says, “When all of the schools started to have walkouts, we started to have a voice. I think, if kids start taking it more seriously, adults will, too.”

Other thoughts from these students:

Arming teachers would not solve the problem says Landeck. “The teachers’ number one job is to be there for their students.” He says carrying guns would place more of a burden on the teachers and points out it would require years of training to know how and when to properly use the gun. Guinness says arming teachers would make him feel less safe. “There’s always kids in classrooms that [could]…find a way to get the gun.”

Arming school security officers—“If the security guards had guns, that’s more understandable than the teachers having guns,” says Guinness. Landeck points out the importance of the relationship between the security officers and the students. “You want to get a security guard that will not only keep the students safe, but also get to know them and relate to them.”

Reporting possible mental health issues in other students—Moore says reporting on peers is difficult in high school. “You never want to lose your relationship with someone … [but when] it’s so very apparent there’s something that [a person] needs help with, I think everyone I know would get help or get the person help.” Landeck, however, is not so sure. “There are people you question, but you don’t feel like it’s your business to get involved or ask what’s going on.”

“We’re never going to squash all mental health problems…so you need to…address some gun safety and some gun legislation, [and] make it harder for a very mentally sick person to get a gun,” says Landeck.

Madeline Seibel Dean is a college student at Vassar who, as a Front Porch intern, interviewed students about school shootings.

0 Comments