Colorado Gov. Jared Polis signs an executive order that rescinds proclamations from Colorado Territorial Gov. John Evans at the Capitol on Aug.17, 2021. Gov. Polis handed sage to the various tribe representatives and speakers after signing. Photo by Rebecca Slezak, courtesy of The Denver Post, https://www.denverpost.com/2021/08/17/colorado-1864-proclamation-native-americans-sand-creek-massacre/

Sand Creek Massacre

On August 11, 1864 Territorial Gov. John Evans issued two orders. The first directed Native Americans to gather at specific camps. The second directed U.S. troops to kill them. Approximately 230 members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes died. The majority of them were women, children, and elders, but 13 Cheyenne Chiefs, four Cheyenne Society Headmen, and one Arapaho Chief also lost their lives.

Gov. John Hickenlooper shakes hands with a tribal leader in a Dec. 2014 ceremony apologizing for the Sand Creek Massacre. Photo from the Colorado governor’s office

![]()

Not everyone participated in the massacre. U.S. Captain Silas S. Soule ordered his troops to stand down. He later testified to the Military Commission about what he saw. “The massacre lasted six or eight hours, and a good many Indians escaped….It was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized….One squaw with her two children, were on their knees begging for their lives of a dozen soldiers, within ten feet of them all, firing—one succeeded in hitting the squaw in the thigh, when she took a knife and cut the throats of both children, and then killed herself. One old squaw hung herself in the lodge—there was not enough room for her to hang and she held up her knees and choked herself to death….I saw two Indians hold one of another’s hands, chased until they were exhausted, when they kneeled down, and clasped around each other the neck and were both shot together. They were all scalped…all horribly mutilated. One woman was cut open and a child taken out of her, and scalped.”

157 years later, Gov. Jared Polis officially rescinded both orders and apologized on behalf of the state. “We can’t change the past,” he said. “But we can honor the memories of those who we lost by recognizing their sacrifice and vowing to do better.” Polis also established the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board which renamed Squaw Mountain to Mestaa’ėhehe (pronounced mess-ta-HAY) Mountain. Mestaa’ėhehe was an important female translator for the Cheyenne Tribe. Other amends include Gov. John Hickenlooper officially apologizing to descendants of the Sand Creek Massacre, the removal of a statue that referred to the massacre as a “battle,” and Colorado banning Native American mascots in the state. Mt. Evans, named after the Territorial Gov. who ordered the massacre, is likely to get a new name next year.

Indian Boarding Schools

Ft. Lewis was a military post turned Indian Boarding School that operated for almost two decades from 1891 to 1910. The purpose of the school was to de-Indian Native American students. A common mantra was, “Kill the Indian; save the man.” Students, some of whom were kidnapped from their homes, were forbidden to speak their native language, pray, or practice any of their cultural rituals. Their hair was cut, and punishment could be swift and cruel. It’s what many have called a complete cultural genocide.

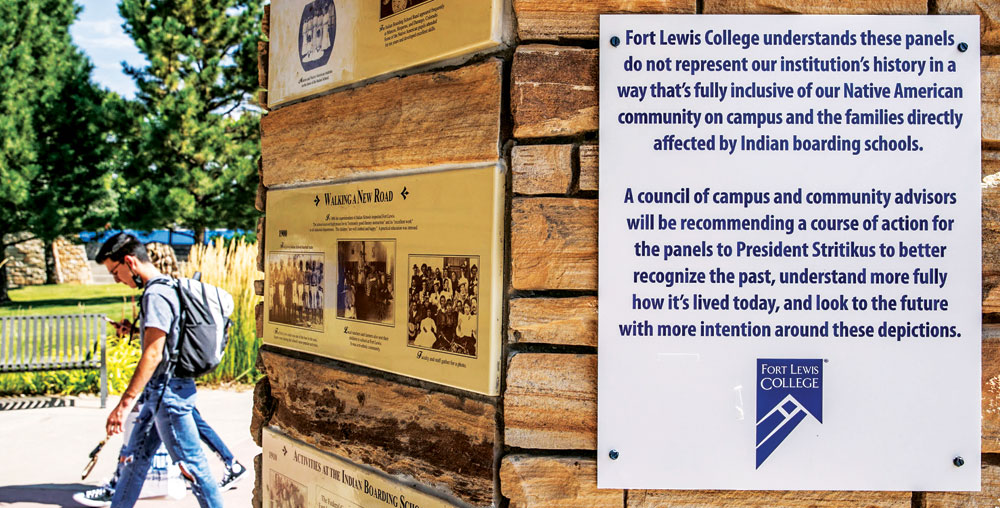

A sign at Ft. Lewis College acknowledges that panels about the history of the Indian School “are not fully inclusive of our Native American community.” Photo by Hart Van Denburg/Colorado Public Radio

![]()

Today, Ft. Lewis College (FLC) sits where the Indian Boarding School used to be. According to their website, about 45 percent of FLC students are Native American. In September, the school removed panels from their iconic clock tower that whitewashed history by portraying images of Natives as carefree and lighthearted. The school is still in the process of determining what art will replace the panels, but they say it will tell the true story of life at the boarding school. Furthermore, FLC will participate in the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate schools that forced assimilation and identify burial sites. According to an article by CNN, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said, “At no time in history have the records or documentation of this policy been compiled or analyzed to determine the full scope of its reaches and effects. We must uncover the truth about the loss of human life, and the lasting consequences of the schools.”

Darius Smith, whose mother attended a Navajo Boarding School in Arizona and who is now the Director of Denver’s Anti-Discrimination Office, says one of the biggest problems still facing Native Americans today is stereotypes. People tend to think all Native Americans live on the reservation, that they’re mass consumers of resources, all living in abject poverty as relics of the past. “When I first started working for the city in 2005,” says Smith, “we had one of the largest conferences in Denver, The National Indian Education Association. They recruited me to staff Mayor Hickenlooper at the time. I wrote this brief all about the positive things Natives were doing. I talked about the Native American Bank and all these native organizations and their accomplishments. And Hickenlooper gets up there in front of 3,500 people, and I’m thinking he’s going to read my brief about all these amazing things American Indians are achieving. And he grabbed my brief, he looked at it, and he looked out in the crowd, and he folded it up and put it back in his jacket, and he started to tell the story of The Sand Creek Massacre. That’s just one example,” says Smith. It’s the narrative—not the Natives—who need to change.

Ku Klux Klan

In April, History Colorado released a digitized version of two Ku Klux Klan ledgers that include 1,300+ pages of names, addresses, and businesses affiliated with the Denver KKK from 1924-26. The ledgers show just how pervasive the Klan was when Ben Stapleton was mayor. Klansmen were employed everywhere from grocery stores and pharmacies to cab companies and the zoo. And while the second wave of the Klan wasn’t known for their violence, their threats and intimidation created a power structure that endured long after they began to fizzle in 1925.

History Colorado’s exhibit on the Ku Klux Klan helps visitors understand how pervasive the Klan was in Denver in the 1920s. Front Porch photo by Steve Larson

![]()

In the last few years, Denver has taken steps to address concerns of racial inequality. Stapleton residents changed the name of their neighborhood to Central Park. While school board meetings across the country became heated, Denver elected a board that has been progressive in addressing equity issues. DPS has implemented implicit bias training for teachers and has worked with Promise 54, a group dedicated to recruiting and retaining educators of color. The board passed The Know Justice, Know Peace Resolution calling for curriculum and professional practices to “include comprehensive historical and contemporary contributions [of] Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities.” It also passed the Black Excellence Resolution that aims to “prioritize student success, be a district that is community-driven and expertly-supported [while] being equitable by design.” In December, Centennial Elementary School made national news for their controversial decision to host their monthly “Families of Color Playground Night.”

When it comes to progress, Norma Johnson—a healer, poetic storyteller, and social justice educator—says people have been talking forever, but others are finally starting to listen. She wrote, “A Poem for My White Friends: I Didn’t Tell You,” which reads in part, “It comes in moments of time triggered by a look, an attitude, a sensing of superiority, of blatant ignorance, of good-meaning intentions dripping crap down my face. I didn’t tell you about the white woman—a stranger—who chose out of all the white people around us to sit next to me and proceed to tell me all about her favorite black performers, her black friends, and how this country needs to take integration to the next level, so I could see how her life is an example of that.” Johnson says when it comes to social justice, she focuses on the momentum that’s occurred throughout generations all the way down to everydayness of life. And she says we’re on the edge of a moral precipice. For so long, narratives were controlled by certain groups. But now, in the digital age, stories that were once marginalized or ignored have a platform. When people can hear, they can ask, ‘What does this mean for my life? Johnson believes the burden of inclusivity and understanding may finally be shifting from people of color to white people.

Amache Internment Camp

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many white Americans began to distrust their Japanese neighbors. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt ordered approximately 120,00 Japanese—the majority of them American citizens—to relocate to internment camps (which some historians say should more accurately be called concentration camps). Amache, which operated in southeast Colorado from 1942-45, housed 7,318 of those souls. One of them was Bob Fuchigami, 91. His parents and seven siblings operated a peach farm in Northern California when they were relocated. Fuchigami was 11. In a YouTube video that superimposes Fuchigami’s experience over a U.S. propaganda film that shows Japanese Americans waving and smiling as they board buses to Amache, Fuchigami explains his experience. “I was still playing with marbles, riding my bike, and taking care of a few rabbits. I thought we were going on a trip to the Sierra Nevadas or something, but then you walked into the room, and there was just one bare light bulb, folded cots, a thin mattress, and some army blankets, that’s it. I remember being told not to go near the fence. You’d get shot,” he says. “There were no charges, no hearings, no due process. The assumption was ‘you’re guilty.’ You haven’t done anything, but you might do something. I always wondered where my place in society would be when I came out. I was 15. I joined the Navy. We were patriotic loyal citizens before camp, while we were in camp, and after we were in camp.”

A docent at History Colorado’s Amache exhibit talks to Northfield High School students in a room recreated to look like an Amache residence. Front Porch photo by Steve Larson

![]()

Two bills have been introduced to establish the Amache National Historic Site as part of the U.S. National Park system. “That’s good,” says writer Gil Asakawa who’s worked to re-envision Denver’s once-booming Chinatown, “but hate crimes still plague the Asian community.”

Last year when Asian hate crimes were on the rise nationwide, Asakawa and a group he helped found, The Colorado Asian Response Committee, met with the DPD Hate Crimes Unit and learned that only three incidents had been reported in Denver. When they followed up a few months later that number had dropped to zero. Asakawa wasn’t surprised. He says the same values that enabled the Japanese to board buses waving and smiling are the same ones that keep Asian Americans from reporting hate crimes. “Gaman” he says, “can be translated into suck it up, work hard, push through. For example, If a Japanese parent is encouraging his kid to finish a daunting school project, he might say, ‘Gaman! Gaman!’ The other is Shigata Ga Nai which means ‘it can’t be helped.’ This is where we live now. This is our government, our community in the United States. Asakawa says just because hate crimes weren’t being reported didn’t mean they weren’t happening. “I can rattle four or five off the top of my head,” he says. “A young Japanese American woman was driving. She had her window down at a stoplight, and a group of young guys started yelling epithets at her and then sprayed her with disinfectant through her window. She was so freaked out, she ran the red light. Another woman was at a laundromat, and a white woman poured bleach all over her folded clothes. A Korean woman had her kids in a stroller at King Soopers in Englewood when a white person spit on her. A friend of mine, who works for the city, was walking on Bannock, when a woman yelled,‘Go back to China!’ We urged them to report these crimes. None of them did because—Gaman! Shigata Ga Nai.

0 Comments