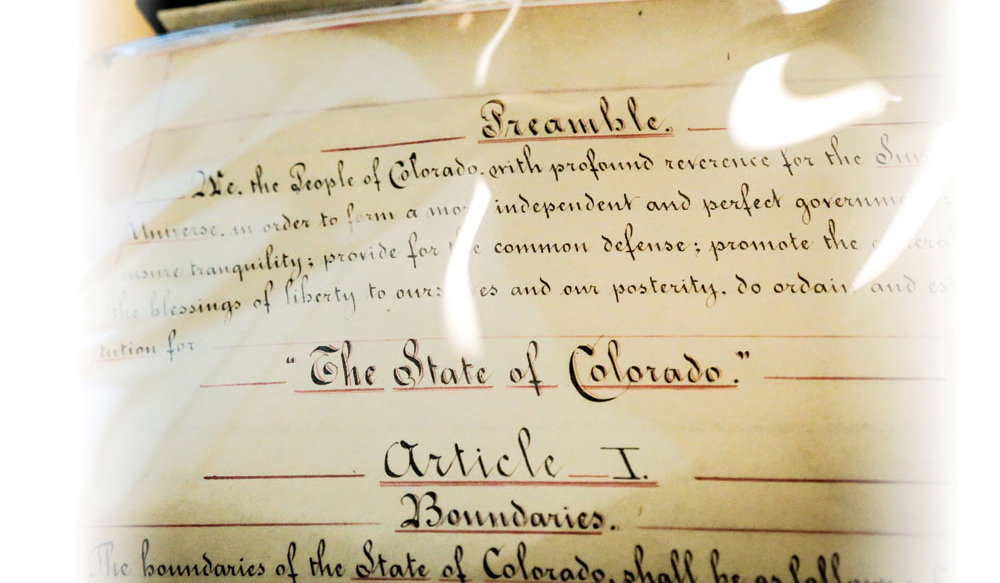

The original handwritten Colorado Constitution is in a sealed case in the Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center in Denver. Once in the Constitution, amendments, as has been seen with TABOR, are difficult to change.

Over the last three decades governors, various legislators, education advocates, construction company executives, business leaders and civic activists have organized to ask Colorado voters to increase taxes to raise more money for the state’s cash-strapped schools, crumbling highways and other needs.

Over the last three decades governors, various legislators, education advocates, construction company executives, business leaders and civic activists have organized to ask Colorado voters to increase taxes to raise more money for the state’s cash-strapped schools, crumbling highways and other needs.

In every case voters—or at least a majority of the adults who bothered to vote—have said, “No thanks” to statewide tax increases, except for one earmarked tobacco tax hike and the brand-new online gambling tax.

The defeat of Proposition CC in this November’s election is only the latest in the string of losses for about a dozen other ballot proposals to fund education and/or transportation since the early 1990s.

Proposition CC wasn’t a tax increase. It merely would have allowed the state to keep tax revenues collected in excess of the annual limits set by the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR), a constitutional amendment approved by voters in 1992.

Despite the defeat of CC, proponents say they aren’t deterred and will pursue other TABOR fixes, including a possible proposal to repeal or otherwise modify TABOR at the ballot box in November 2020. That effort is being coordinated partly by the Colorado Fiscal Institute, a think tank that analyzes state financial issues.

Two key questions are at the center of the debate over TABOR.

Does Colorado need more tax revenue?

For many people, the objective answer to that question is yes. Colorado has a multi-billion dollar backlog of transportation projects. On the subject of K-12 education, Colorado teachers are among the lowest paid in the nation, and more and more state school districts, especially in rural areas, have moved to four-day school weeks, partly to conserve financial resources.

But subjectively, the answer to that question depends on one’s beliefs about government. Conservative policymakers and some voters believe the state has plenty of revenue—it just needs to prioritize spending differently. (The shop-worn canard about “waste, fraud and abuse,” however, is, a fantasy. Colorado state government is generally lean and efficient.)

What some conservatives are particularly exercised about is the growing cost of Medicaid benefits. If medical spending could be trimmed, they argue, there’d be more money for education and highways. Some conservatives also argue that too much education spending is diverted to administrative costs, an argument that’s never been proven.

Why do Colorado citizens keep saying “no” at the ballot box?

Since TABOR was enacted, voters have approved hundreds of local tax increases and lifted many local revenue caps. Why are they reluctant at the state level?

First, ballot measure language is confusing—intentionally so. Some of the more obscure provisions of TABOR require stilted ballot language that can be confusing to voters.

Voters who are confused or uncertain about ballot measures tend to vote no.

Second, voters don’t seem to be as connected to state government as they are to local issues. Think about it—state government is responsible for services that most people don’t use—or, more importantly—don’t think they use.

Most Coloradans aren’t prisoners, don’t receive Medicaid benefits, don’t go to state colleges or receive public assistance—among the major parts of state spending. Those are major drivers of the state budget, but most citizens don’t use those services. Almost everyone drives or travels on state highways, but many people have a limited understanding of how those are funded.

One of the biggest pieces of state spending is aid to local school districts, but most voters also don’t have a detailed understanding of how schools are paid for. And, the majority of Coloradans don’t necessarily have a direct connection to public schools— they’re either childless or their kids have moved on from the public schools.

Third, Colorado voter turnout often is anemic, and that affects voting on ballot measures.

The turnout for the November election was about 41 percent, or about 1.5 million votes out of 3.8 million voters. (More than 600,000 other Colorado adults aren’t even registered to vote.)

Of those who voted, approximately 32 percent were Democrats, 35 percent were Republican and 32 percent were unaffiliated. Republican voters generally tend to be older and more skeptical of taxes, so they often swing the results in low-turnout elections.

Those three factors highlight the challenges for advocates of state fiscal reform. They have to find more compelling reasons to convince voters, and they really need to work on a ground game to turn out voters.

What the defeat of CC means to you

Most taxpayers don’t receive a check in the mail each year that revenues exceed the TABOR limit. Instead, state legislators have given TABOR refunds indirectly, such as the property tax reduction to seniors and some veterans. In some large-refund years tax rates can be lowered temporarily.

Todd Engdahl is owner of Capitol Editorial Services, a firm that provides legislative coverage, intelligence and analysis to private clients. During a long career as an editor and public policy writer, he served as executive city editor of The Denver Post, founder of DenverPost.com and founder of Education News Colorado, which later became part of Chalkbeat Colorado.

So if I follow Mr. Engdahl’s logic, should the state pass legislation that any refund claimed on an individual’s state income tax return will not be refunded but rather shall be kept by the state, this would not be an increase in tax. It would merely allow the state to keep “excess revenues” collected. Anyway you phrase it, if the state is keeping more funds it is a tax

You lost me at: “Proposition CC wasn’t a tax increase. It merely would have allowed the state to keep tax revenues collected in excess of the annual limits”

Overpaying and not getting the refund is the same thing as a tax increase. That’s why when you overpay your income tax, you can get a refund at tax time.

You would have those due a tax refund to allow the government to keep that money, and not call it a tax increase.

“No tax increase” should have read “no tax rate increase.”