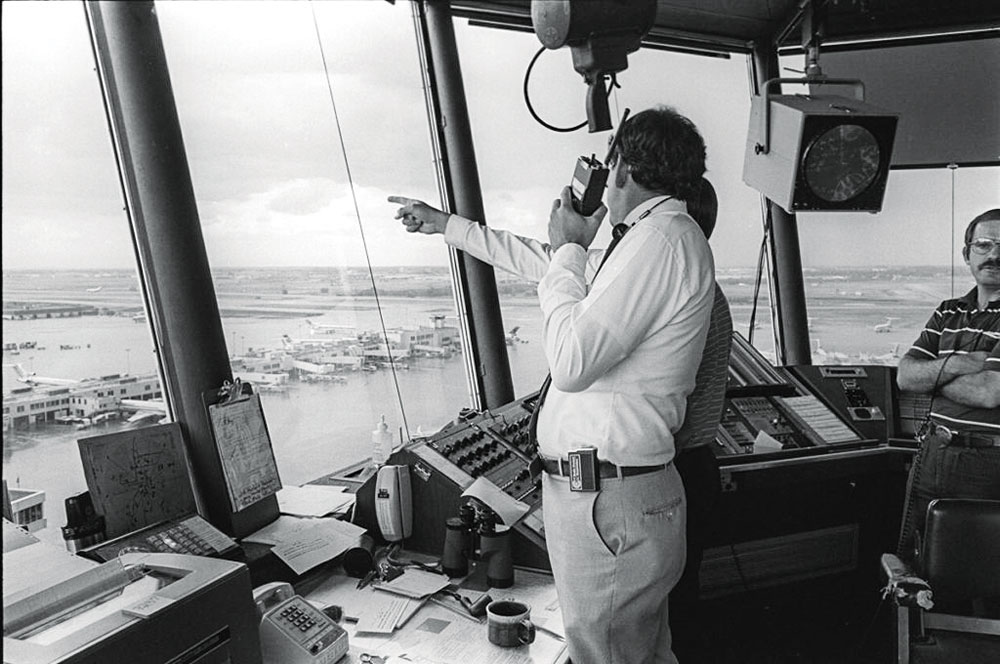

National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist John McCarthy works in the Stapleton control tower in 1984. Photo courtesy of NCAR

They sounded like grizzled war veterans, recounting the close bonds that were formed in tight quarters and under stressful conditions. But there was also a lot of laughter and teasing, as nearly two dozen retired air traffic controllers gathered at FlyteCo Tower in Central Park to mark the 30th anniversary of the closure of Stapleton International Airport.

“It was one of the most difficult airports in the world for air traffic controllers,” says Chuck Dickinson, who started working at Stapleton in 1988. “It was like always trying to put a 10-pound bag of you-know-what into a 5-pound bag,” he says as his former colleagues laughed and nodded in agreement.

Retired air traffic controllers gathered at FlyteCo Tower to reminisce about the closing of Stapleton Airport. Photo by Mary Jo Brooks

“Your ability to survive the day-to-day depended on being able to count on the person sitting next to you,” says John Haman, who became a controller during the 1981 strike when President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 striking air traffic controllers.

Haman says Stapleton was especially stressful because it was an “overburdened” airport. “The runways were too close together. In good weather, we could run a lot of planes, but if there was a thunderstorm or snowstorm, it became a nightmare.”

During a 60-minute panel discussion hosted by FlyteCo Brewing, the former controllers mostly recalled humorous stories—like when Dickinson didn’t know the movie Die Hard 2 was being filmed outside baggage claim one night until suddenly Bruce Willis emerged from an artificially-created snowstorm.

During a 60-minute panel discussion hosted by FlyteCo Brewing, the former controllers mostly recalled humorous stories—like when Dickinson didn’t know the movie Die Hard 2 was being filmed outside baggage claim one night until suddenly Bruce Willis emerged from an artificially-created snowstorm.

But the men also acknowledged more somber events. Jim Bristow recalled how in 1978 and in 1982 planes landed at Stapleton after they had been hijacked. “FBI agents swarmed the tower to negotiate with the hijacker,” recalled Bristow. In both instances, no one was hurt.

Bob Graham, 93, was actually off-duty, mowing his lawn at the edge of Aurora in July 1961 when he saw a DC-8 plane crash and burst into flames. He says he immediately went to the airport to help. “There was very little security then, so I climbed over the fence and went up into the tower. They didn’t close the airport even as the plane burned,” says Graham.

Other controllers remembered when a United Airlines plane was taking off in 1984 and wind shear caused the aircraft to hit an antenna, damaging the fuselage. The plane landed safely and no one was injured. Three years later, however, a Continental Airlines plane waited too long after de-icing and crashed after takeoff. Twenty-eight people died.

Haman says those were terrible events, but if there was a silver lining, it was that they forced the industry to improve. “The Continental crash really cemented the importance of de-icing.” And the aborted United flight made the industry “pay more attention to wind shear and microbursts,” says Haman.

Many of the controllers talked about how bittersweet the 1995 closing of the airport was, even though the facilities at the new Denver International Airport made their jobs easier. Haman says at Stapleton, controllers were so close to everything: the planes, the ramp workers, the passengers. “There was a lot more camaraderie there and, frankly, a lot of that went away with the new airport.”

After the panel discussion, many of the retired controllers climbed up the 11 flights of stairs to look out the tower windows once again. This time, instead of rows of airplanes, they gazed at rows of houses. But as one former controller says as he looked at the mountains, “this was a view that never got old.”

0 Comments