A reproduction of Rivera’s fresco, Man, Controller of the Universe (1934), from Mexico City’s Palace of Fine Arts. Lenin, Marx, Engels and Trotsky appear as does a martini-swilling John D. Rockefeller, oblivious to the workers’ suffering and seated under a dish of syphilis bacteria.

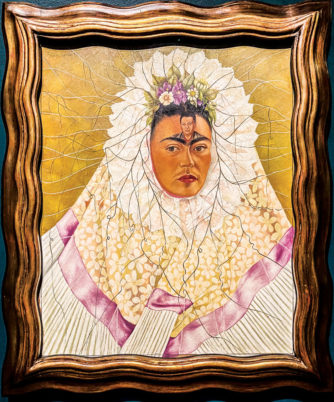

Kahlo’s Diego on My Mind (1943), shows her in a Tehuana headdress.

“It was the entrance of an Aztec goddess,” writes Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes of the one time he saw Frida Kahlo in person. Her arrival in Mexico City’s Palace of Fine Arts caused a stir. The occasion was a concert, but the music of her arrival was her own: “the apparition that announced herself with an incredible throb of metallic rhythms and then exhibited the self that both the noise of the jewelry and the silent magnetism displayed.”

Confined to bed for much of her life due to childhood polio and a devastating streetcar accident, Fuentes concludes that Kahlo was in fact “more like a broken Cleopatra” than an Aztec goddess. In her diary, Kahlo writes “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.”

Fame and Facemasks

Born to a Jewish-German immigrant father (whose photos also appear at the DAM) and a Catholic Mexican mother who was part Spanish, part Tehuana from Oaxaca, Kahlo has come to represent the quintessential Mexican identity. This would likely please her, as she and her husband, artist Diego Rivera, helped to define and construct Mexicanidad. This interpretation of Mexican identity found its principal roots in Mexico’s indigenous people and traditions. Kahlo and Rivera were among many intellectuals of the period after the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) who rejected the Spanish colonial influence and elevated native cultures to create a Mexican identity and aesthetic.

Rivera’s Calla Lily Vendor (1943), depicts traditional dress and hairstyles.

— For video on the exhibit, CLICK HERE —

The Denver Art Museum’s Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism exhibit, conveys some of the power of Kahlo’s personality. The exhibit is from the private collection of Jacques and Natasha Gelman. Twenty of Kahlo’s works complement 130 others that either center on her or add context and understanding to her life and times. The exhibit illuminates both the solitary Kahlo and the Kahlo who formed an integral part of a vibrant community of artists, intellectuals and revolutionaries at a particularly rich moment in Mexican life. Intimate photographs by luminaries such as Lucienne Bloch and Lola Álvarez-Bravo contrast with the abundantly public and mass-reproduced images of her self-portraits that became ubiquitous in the late twentieth century.

Four or five decades after her 1954 death, Kahlo gained a fame that she never experienced during her lifetime. Her Casa Azul home in Coyoacán has become a pilgrimage site. On any given day, tourists from around the globe form long lines to see where she and husband Diego Rivera lived. Facebook popup ads hawk everything from t-shirts and tote bags to facemasks with her likeness.

Politics and Activism

Kahlo and Rivera shared a love for political activism, and here participate in an anti-fascist demonstration in Mexico City, 1936.

Perhaps less pleasing to Kahlo would be the mass marketing and consumerism wrapped up in her image. The commodification of all things Kahlo is a striking contrast to her Communist principles. Kahlo joined the Young Communist League in 1927, at age 20. Both she and Rivera were longtime members of the Mexican Communist Party, even after it was banned. They often marched against fascism and imperialism and on behalf of Mexico’s working class. When Josef Stalin exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, the couple hosted Trotsky and his wife Natalia for almost two years in their home. Just days before her death in 1954, Kahlo—sitting in a wheelchair—demonstrated with 10,000 other Mexicans against the U.S.-orchestrated coup in Guatemala. When she died, Rivera cloaked Kahlo’s coffin in a flag emblazoned with the hammer and sickle, an image she included in paintings and on the orthopedic corsets she had to wear. In short, politics were fundamental to her identity and work.

Though politics are largely absent from the DAM exhibit, two photographs show Kahlo and Rivera demonstrating against fascism and in solidarity with workers. The reproduction of Rivera’s mural prominently features the proletariat and Communist leaders. This is a revised version of the mural that he had started painting in 1933 in the lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Nelson Rockefeller had it plastered over when Rivera refused to remove its portrait of Lenin.

The Context

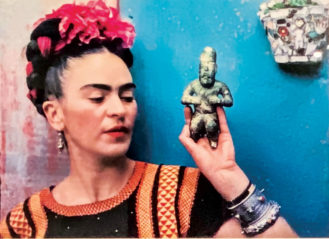

Elevating Mexico’s native cultures was fundamental to Mexicanidad, which the DAM describes as a movement that “merged indigenous culture with national heritage.” In this Nickolas Murray photo, Kahlo holds an Olmec figurine.

Though Kahlo is definitely the headliner here, in addition to 20 of her works, the exhibit includes prominent pieces by Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Miguel Covarrubias, David Alfaro Siqueiros, María Izquierdo, Carlos Mérida, Lola and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and others who defined Mexican identity and Mexican modernism in the mid-twentieth century. The exhibit design, from its colors to its shapes, takes its inspiration from pre-Columbian forms and colors (recall that Mexico’s pyramids used to be covered in gorgeous color).

“From working in Detroit, I knew we could tell a story,” says curator Rebecca Hart. Hart has a special affinity and expertise in Mexican art, and was previously at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), where Rivera and Kahlo spent time in the early 1930s. Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals remain a point of pride for the DIA, and even Rivera’s scaffolding has a hallowed place in storage there.

The exhibit will be at the DAM through January 24, 2021, and for those wishing to learn more about Mexican modernism, the DAM is offering an online course as well.

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

Rufino Tamayo’s Portrait of Cantinflas (1948), reflects Mexico’s Golden Age of cinema. It depicts a beloved comedic character, the subject of more than 30 films.

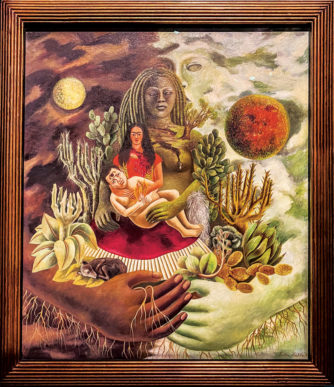

Kahlo’s, The Love Embrace of The Universe, The Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xolotl (1943). Señor Xolotl was her dog, an itzcuintli

0 Comments