“Coming here, it wasn’t the ‘American Dream,’” says Thania, a migrant from Venezuela. “When you arrive, you suffer because you can’t work.” Three months after arriving, she and her spouse are still awaiting work permits.

They enter the City of Denver’s official reception center in North Denver carrying their few belongings in plastic grocery bags. Most have arrived from Venezuela, fleeing a 95 percent poverty rate, lured by the hope of a better life. Desperate, more people have left Venezuela than have fled the war in Ukraine. By the time they reach Denver, they have traveled through seven countries.

Denver, a sanctuary city, is among many that are receiving migrants due to the biggest humanitarian crisis in the western hemisphere. Dressed in sweatpants and sweatshirts, even the toddlers at the reception center are remarkably calm. One little boy, in a Spiderman outfit, fidgets on the hard plastic seat. As parents take out their identity cards, the children pass them around, gazing at the photos with curiosity.

A Harrowing Journey

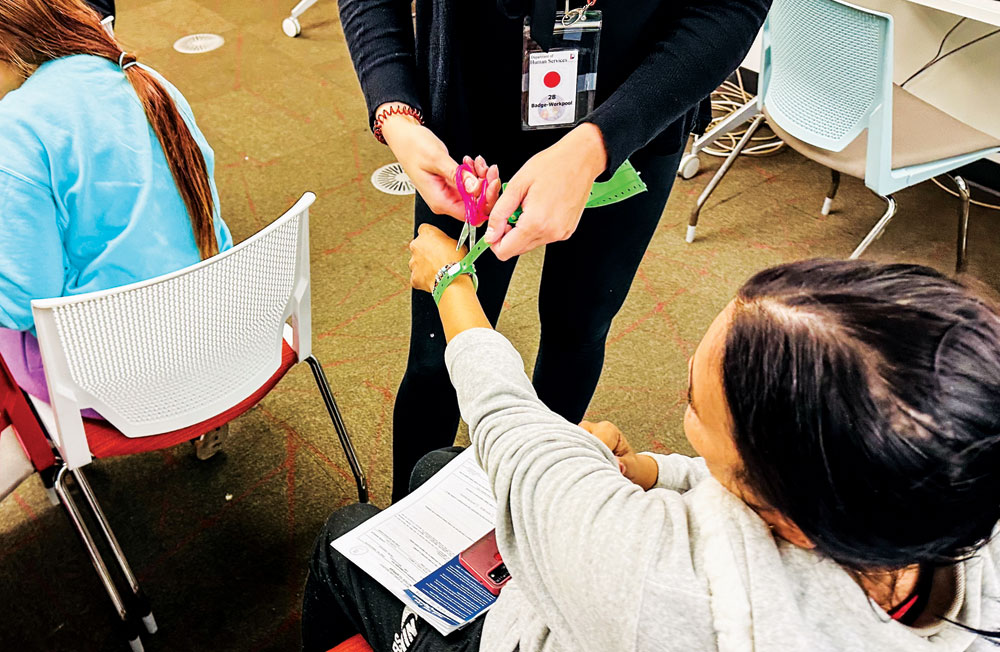

It took Angie and her family four months to get to this reception center. (Front Porch is only using first names to protect the identities of the migrants.) They walked, rode buses, and finally, climbed atop “la Bestia,” or “the Beast,” also known as “the Train of Death.” Migrants ride from Mexico City atop this freight train to the border of the U.S. Angie’s husband and two children—third and sixth graders—sit quietly as they receive wristbands that direct them to the next stop on their journey. With luck, they will be assigned a hotel.

But the City has little space to house the newcomers. More than 33,000 migrants—mostly Venezuelans—have arrived in Denver since December 2022. The numbers change so rapidly that the City updates its migrant dashboard three times a day. While some migrants have moved on to other cities, the influx isn’t slowing. Just in the first five days of December, 13 buses arrived from Texas.

The City recently suspended the length-of-stay limits at migrant shelters. While families previously could only stay in shelters for 37 days, now families with children can remain in shelters indefinitely to ensure that their kids are housed in these cold temperatures. In January, the City expects to announce an agreement with a housing subcontractor, says Deputy Chief of Staff Evan Dreyer, who could not share further details before press time.

The City recently suspended the length-of-stay limits at migrant shelters. While families previously could only stay in shelters for 37 days, now families with children can remain in shelters indefinitely to ensure that their kids are housed in these cold temperatures. In January, the City expects to announce an agreement with a housing subcontractor, says Deputy Chief of Staff Evan Dreyer, who could not share further details before press time.

Dreyer would like to see Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) provide temporary work authorizations at the same time that they are permitting people to enter the U.S., thus allowing people to legally work while they await their court dates. This way, migrants would “gain self-sufficiency and not have to rely on local governments to put them up in a shelter.”

Denver Mayor Mike Johnston’s administration has, along with municipal governments around the country, asked the Biden administration to fast-track and increase the number of work authorizations for migrants. The mayors also requested $5 billion in aid from the federal government to help with the migrant crisis. So far this year, Denver has spent more than $33 million to support the immigrants.

At the City of Denver’s migrant reception center in NE Denver, newcomers show their identity cards and receive wristbands to get placed into shelters.

Every Venezuelan migrant who spoke to Front Porch expressed a powerful desire to be self-sufficient and not burden the system. Thania and her husband had to leave two children in Venezuela because her mother insisted the journey was too dangerous for them. Driven by the need to provide for their family, they walked for four days, hungry, through the jungle in Colombia and Panama. They saw people dead and dying from thirst, hunger, and exertion. They rode the Bestia through Mexico even though by this time Thania had learned she was pregnant. Getting to the U.S. as quickly as possible was the priority.

The couple eventually found an apartment here. A stranger who saw Thania panhandling helped pay their rent, but as December neared, she was understandably concerned. Her spouse had found some work, but the employer refused to pay him.

Denver has a wage theft ordinance that expressly covers workers regardless of their immigration status, though some employers bank on laborers fearing to report it. Any worker in Denver has a right to make a complaint to Denver Labor, which also accepts anonymous and third party complaints.

“There are plenty of jobs. We have thousands of people who have come here who want to work in multiple industries and economic sectors, but we have federal rules that stand in the way of connecting jobs and job seekers with employers,” says Dreyer. Some non-profits are helping migrants establish LLCs as a temporary workaround.

Northeast Denver Moms Respond to the Crisis

“It’s all organized by moms,” says Carla Lewis, a Central Park mother who hands out hygiene products in the parking lot of the Motor Vehicle Division on Peoria St. on a blustery afternoon. Area moms are coordinating donations of meals, rides, diapers, second-hand clothing, and even rental assistance. At distribution events, car trunks and minivans sit open so people can “shop” for the items they need.

Sofie (left) and Carla Lewis (right) are among many in the Central Park and Park Hill neighborhoods who have distributed hygiene products, clothes, and suitcases at community-organized distribution events. Most newcomers have traveled for months on foot and need new items after using all of their supplies or being robbed during the journey.

This grassroots momentum accelerated as the temperatures dropped. The “Central Park & Park Hill—Venezuelan Migrant Support” Facebook group had over 1,400 members within two weeks of its November founding. Members share information about how to enroll in school or access medical care, and an Amazon wish list circulates with ongoing needs, such as socks and underwear.

Volunteers recently delivered used furniture to Kimberly, Adonis, and their three children. The family found an apartment after walking for miles while knocking on doors and asking for vacancies. Adonis secured a one-month construction job, but like Thania’s husband, fell prey to wage theft when he tried to collect his pay after two weeks. Adonis told Front Porch his priority is enrolling his children in school. He wants them to have more opportunities and learn English. Kimberly will look for work once the kids have settled in.

For some, being settled remains a dream. Candice Marley’s non-profit, All Souls Matter, provides tents and propane heaters to migrants who lack housing and are living in camps around Denver. All Souls has proposed safe camping and parking zones in meetings with officials, but as of press day, the City had not sanctioned either. Marley says that the cost of washing stations, mobile showers, and port-a-potties is far less than conducting sweeps and cleaning up sites without these services.

“We can’t get around the fact that people are going to be living in tents unless Denver magically finds more migrant hotels. They want to work as fast as possible,” says Marley, whose accounting firm is helping migrants establish LLCs. “But it’s going to take a few months, either way, to get out of the tents.”

Angie and her family plan to make a life in Denver. They will change their June 2024 New York immigration court date and give Denver a try since this is where they landed. Kimberly and her family, who arrived in August, will go to court in January 2025.

To help families get into permanent housing, consider donating to the Newcomers Fund managed by Rose Community Foundation: https://rcfdenver.org/nonprofits-and-grants/what-we-fund/newcomers-fund/

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments