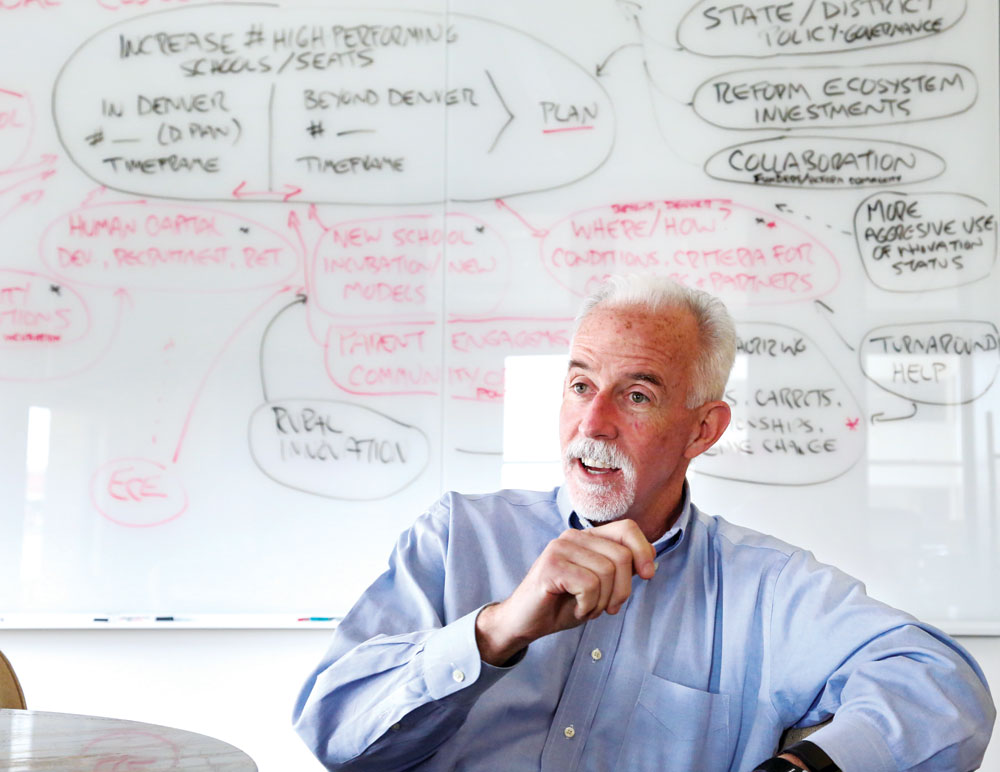

Tom Gougeon, called a visionary by many, was the primary author of the Green Book. He is pictured at the Gates Family Foundation, where he is now president.

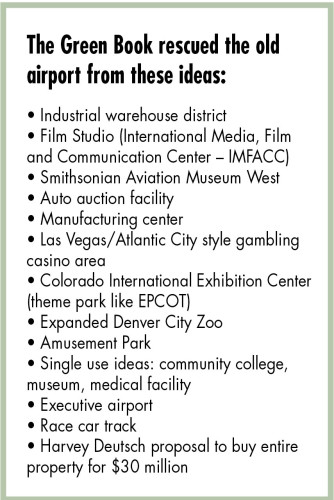

It’s possible that without the vision in the “Stapleton Development Plan” (the Green Book), the abandoned Stapleton International Airport could have become an industrial warehouse district, a large theme park, an auto auction site or a race track. Twenty-five years ago, the question of how to re-purpose seven square miles of soon-to-be vacant, contaminated and fenced-off inner-city land was so daunting that the temptation was to succumb to the first money-making idea that came along.

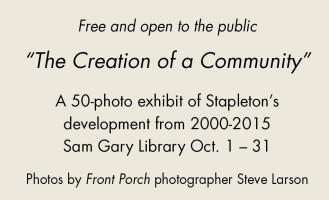

This rendering, printed in the third issue of the Front Porch in fall 2000, shows “different architectural treatments that create varied and memorable streetscapes reminiscent of Denver’s most attractive neighborhoods.” The photo at right, taken in 2006, shows the outcome was remarkably close to the vision. Illustration courtesy of Forest City Stapleton Inc.

And the question of what to do with the land was playing second fiddle to an even larger project—creation of the 53-square mile Denver International Airport (DIA). Not only that, the administration of newly elected Mayor Wellington Webb was besieged with a laundry list of infrastructure issues that could have relegated Stapleton to the back burner. In a recent interview, Webb catalogued what was on his plate at the time: Coors Field, renewing the Winter Park resort lease, building the Pavilions shopping center downtown, negotiating leases with Denver’s major league teams, LoDo revitalization and loads of neighborhood-specific projects.

To download a timeline of the development of Stapleton from 1985 to 2061, click here.

Denver in the ’80s

Like many central cities across the country, Denver was losing population due to the continued infatuation with post-war suburbia. It also faced the local challenges of white flight due to busing and an energy bust that devastated the Front Range economy. More particularly for the future Stapleton residential project, northeast Denver had pockets of deep poverty and gang violence was peaking.

Meanwhile, there was Stapleton International Airport itself, so constrained for space that its east-west runways didn’t meet FAA standards for separation and the north-south runways spanned I-70 on bridges. Park Hill residents had to suspend their backyard conversations as planes approached for landings from the west. Patients at the Fitzsimons Army Hospital had an eye-level view into airliner cockpits as planes arrived from the east. And there was anxiety about the possibility of a plane crash at the airport or in the neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, there was Stapleton International Airport itself, so constrained for space that its east-west runways didn’t meet FAA standards for separation and the north-south runways spanned I-70 on bridges. Park Hill residents had to suspend their backyard conversations as planes approached for landings from the west. Patients at the Fitzsimons Army Hospital had an eye-level view into airliner cockpits as planes arrived from the east. And there was anxiety about the possibility of a plane crash at the airport or in the neighborhoods.

Stapleton also had its supporters—people who flew regularly and enjoyed its accessibility without living under the flight patterns. But as the city encroached, and especially with the onset of jet aircraft, the issue of airport relocation became a Denver City Council topic of discussion as well as the stimulus for neighborhood lawsuits.

Along comes Denver’s newly elected and first-ever Latino mayor, Federico Peña. In running against the political establishment, the young, energetic Peña had the audacity to embrace the idea of relocating the airport. He saw a win-win of gigantic scale in the closure of Stapleton: creating a development opportunity on seven square miles in the city while also building a new airport on 53 square miles located far away from any neighbors who might complain. This was a Big Bang theory of urban revitalization.

A few obstacles lay in Pena’s way. They included the fact that the land needed for a future DIA was located well beyond the corporate limits of the City and County of Denver—and Denver was prohibited from unilateral annexations by a state constitutional amendment. Solutions to that problem would require intergovernmental agreements and public votes. Some were aghast at the remoteness of the DIA site. And, of course, there was the whole question of how all of this was to be financed.

Ultimately, Peña prevailed in his arguments and the Denver City Council, in 1985, reached agreement in principle to build DIA. Public votes in 1988 and 1989 sealed the deal. DIA would open a few years hence and the Stapleton airport would be abandoned. Could a 4,700-acre liability somehow become a public asset?

How the Green Book Came to Be

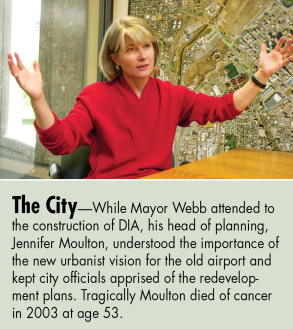

In 1993, when Mayor Webb took office, he was knee-deep in building projects, with his primary focus on DIA. Stapleton could have gotten lost in the shuffle. But a fortuitous convergence of factors kept the redevelopment effort alive. The vision of a new urbanist community had three essential and complementary pillars of support: neighborhood activists who wouldn’t take no for an answer, passionate civic leaders willing to put both money and leadership into the cause, and city leaders who understood and supported the vision.

In 1993, when Mayor Webb took office, he was knee-deep in building projects, with his primary focus on DIA. Stapleton could have gotten lost in the shuffle. But a fortuitous convergence of factors kept the redevelopment effort alive. The vision of a new urbanist community had three essential and complementary pillars of support: neighborhood activists who wouldn’t take no for an answer, passionate civic leaders willing to put both money and leadership into the cause, and city leaders who understood and supported the vision.

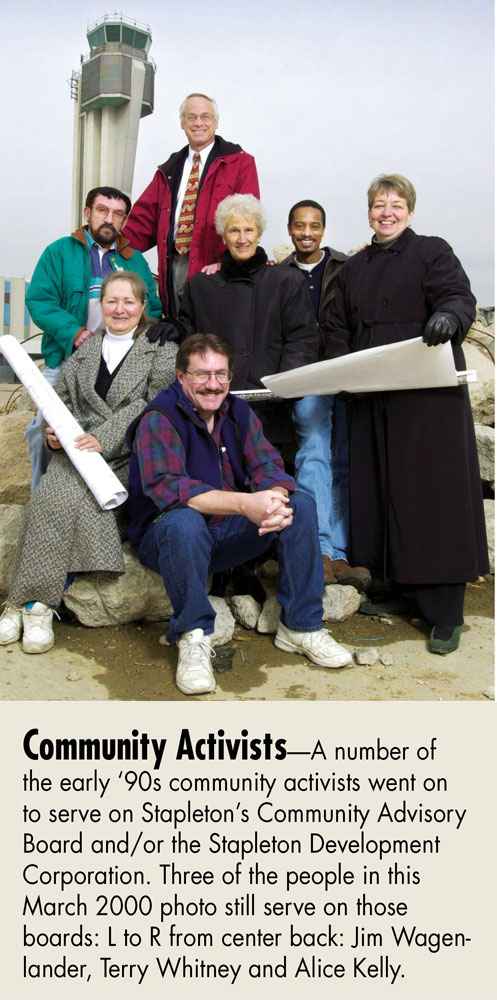

In 1989, Peña’s forward-looking group, the Stapleton Tomorrow Citizens Advisory Committee, began developing a list of ideas and a concept plan. Original member Alice Kelly said early on (and continues to say) the vision was to have a “live-work-play” neighborhood for everyone from a CEO to a table waiter. The committee also expressed to the mayor their fear of development proceeding piecemeal starting on the perimeter and evolving into who knows what.

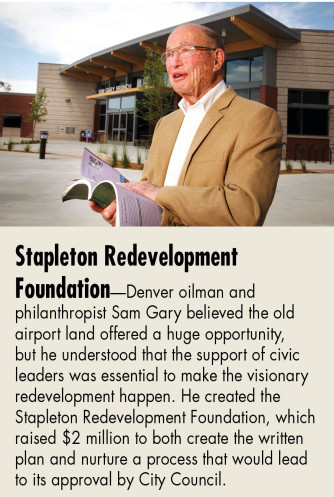

Meanwhile, the second of the three pillars that undergird the Green Book began to form in the mind of Sam Gary, an oilman and philanthropist. Gary said in a 2013 interview with the Front Porch, “I think Stapleton struck me as being a huge opportunity because I’d lived in New York City and seen urban sprawl in other cities in America. I saw it simplistically—that if one could somehow wrest it (the airport) away from the normal processes, it would be a huge opportunity to break the pattern (of urban sprawl). It was simplistic but I found it simplistic enough that I could understand it. So I embarked on this very naïve journey that involved a number of friends who believed there was no such thing as ‘How?’ It was ‘Why not?’”

Meanwhile, the second of the three pillars that undergird the Green Book began to form in the mind of Sam Gary, an oilman and philanthropist. Gary said in a 2013 interview with the Front Porch, “I think Stapleton struck me as being a huge opportunity because I’d lived in New York City and seen urban sprawl in other cities in America. I saw it simplistically—that if one could somehow wrest it (the airport) away from the normal processes, it would be a huge opportunity to break the pattern (of urban sprawl). It was simplistic but I found it simplistic enough that I could understand it. So I embarked on this very naïve journey that involved a number of friends who believed there was no such thing as ‘How?’ It was ‘Why not?’”

Gary formed the Stapleton Redevelopment Foundation (SRF) in 1990 and the original thought was that the SRF itself would purchase the Stapleton property. Concerns over total acquisition cost, including undetermined environmental cleanup costs, eventually squelched that idea. Attention turned to preparing a master plan for the land. One of the SRF’s first hires, Tom Gougeon, said, “Stapleton needed a framework. You couldn’t just go out there and randomly start developing. Most people I think got that.

“Stapleton had been an island all its life as an airport—it’s a fenced island. So this is your one chance to reconnect that island to what’s around it. Stapleton had never been anything that an adjacent neighborhood would want to connect to.”

Citizen interest continued unabated, and in 1993, Mayor Webb created a successor to Stapleton Tomorrow when he appointed the Stapleton Citizens Advisory Board (CAB). Gougeon observes, “I don’t know that a bunch of CEOs and executives and philanthropic leaders could have carried the day. I think it needed people in the community to say—‘These are the right things’. Then it went from there.”

Citizen interest continued unabated, and in 1993, Mayor Webb created a successor to Stapleton Tomorrow when he appointed the Stapleton Citizens Advisory Board (CAB). Gougeon observes, “I don’t know that a bunch of CEOs and executives and philanthropic leaders could have carried the day. I think it needed people in the community to say—‘These are the right things’. Then it went from there.”

The CAB continues to this day acting as the conscience, along with the Stapleton Foundation, for the Green Book, meeting monthly and providing year-end reports on Forest City’s performance. CAB is multi-jurisdictional with members from adjoining local governments as well as representatives from adjacent Denver neighborhoods.

The SRF and Webb administration discussed preparation of a master plan for Stapleton. Gary’s group raised nearly $2.5 million and, according to Gougeon, primary author of the Green Book, eventually gained enough credibility with the city to receive the go-ahead to prepare the plan. The city contributed $500,000 in cash and in-kind support to the master plan project. The city/SRF partnership was formalized in June of 1993.

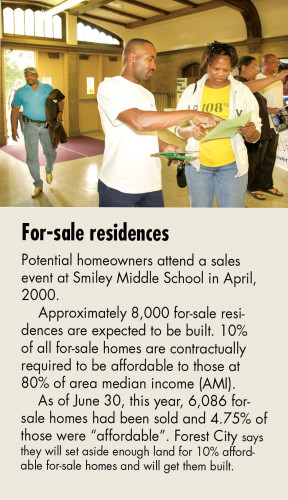

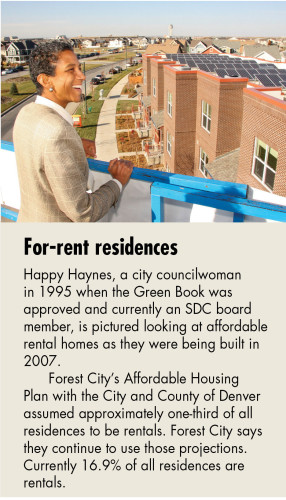

So, by this time the vision had three solid pillars of support and what remained was to crystalize the bold thoughts into a plan for development. In some sense, the notion was pretty simple. As Happy Haynes, a city councilwoman throughout the ‘90s, has said, “It was the idea of capturing the best parts of Denver.”1 Tom Gougeon described it as place-making, “We wanted everything to be mixed, so it was less about land use and more about character. I think we were trying to describe the essential ingredients of place-making.”

And who was Tom Gougeon? He was a Harvard-trained urban planner who had been a senior aide to Mayor Peña and became the project leader for the Stapleton Development Plan project. He assembled a staff including Jim Chrisman, who went on to work for Forest City and remains their senior vice president in charge of development for Stapleton. Gougeon says, “We didn’t think there was a conflict between doing the best for the community and creating economic value.” Consultant contracts for studies began in September of 1993. Major public meetings were held throughout 1994 and, in March 1995, the Denver City Council approved the plan.

According to Jim Wagenlander, a CAB member for 23 years, the plan was an answer to those who thought that an abandoned airport couldn’t be anything more than an industrial area. The Green Book’s expansive vision was soon being recognized nationally (by the EPA and the Urban Land Institute among others) and internationally (by the Stockholm Partnerships for Sustainable Cities Award). King Carl Gustaf presented the Stockholm award for the Stapleton redevelopment in 2002.

Hiring a Developer

The Green Book recommended the creation of a nonprofit corporation to manage the Stapleton site and redevelopment project—and the Stapleton Development Corporation (SDC) was approved by city council a month after the Green Book was approved. The initial idea was that SDC would be the master developer. Staff were hired and protracted negotiations began on how the land would be conveyed from the Denver Department of Aviation. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was involved because they needed to ensure that a “fair” price was paid for the land. There were major disagreements on the value of the land considering the lack of infrastructure and the unknowns concerning environmental pollution. Mayor Webb insisted on almost 25 percent open space, which the FAA feared would lower the total selling price because that land would not be sold—it was given to Denver.

The Green Book recommended the creation of a nonprofit corporation to manage the Stapleton site and redevelopment project—and the Stapleton Development Corporation (SDC) was approved by city council a month after the Green Book was approved. The initial idea was that SDC would be the master developer. Staff were hired and protracted negotiations began on how the land would be conveyed from the Denver Department of Aviation. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was involved because they needed to ensure that a “fair” price was paid for the land. There were major disagreements on the value of the land considering the lack of infrastructure and the unknowns concerning environmental pollution. Mayor Webb insisted on almost 25 percent open space, which the FAA feared would lower the total selling price because that land would not be sold—it was given to Denver.

Things dragged on and a stalemate of sorts settled among the players. Eventually, the city administration and some of the CAB members came to the decision that the SDC did not have the capacity to be its own master developer. Dick Anderson, a veteran developer of large and complex projects, was brought in as president and CEO of SDC the last week of 1997 and prepared SDC for its new role, which included soliciting a private, master developer. The land value of Stapleton was established, DIA obtained an insurance policy limiting its cost of environmental remediation, and Denver signed the pivotal 1998 Master Lease and Disposition Agreement giving SDC authority to sell Stapleton land. SDC then proceeded to find a master developer, a process concluded in 2000 with the selection of Forest City.

Things dragged on and a stalemate of sorts settled among the players. Eventually, the city administration and some of the CAB members came to the decision that the SDC did not have the capacity to be its own master developer. Dick Anderson, a veteran developer of large and complex projects, was brought in as president and CEO of SDC the last week of 1997 and prepared SDC for its new role, which included soliciting a private, master developer. The land value of Stapleton was established, DIA obtained an insurance policy limiting its cost of environmental remediation, and Denver signed the pivotal 1998 Master Lease and Disposition Agreement giving SDC authority to sell Stapleton land. SDC then proceeded to find a master developer, a process concluded in 2000 with the selection of Forest City.

Dick Anderson says it was Forest City’s commitment to the Green Book that really stood out among the finalist teams. General statements in the Green Book about housing affordability and diversity were translated into hard numbers in subsequent development agreements (see sidebars). Forest City committed to purchasing airport property at a specified rate and to getting actual development underway. The first residents moved to Stapleton in 2002.

A plethora of other arrangements concerning financing were necessary. (Explanations of them can be found on the Front Porch website.) Prominent among these are the formation of metropolitan districts to collect taxes and build infrastructure, and the use of tax increment financing that allows sales tax revenues in Stapleton to support development of infrastructure for up to 25 years before those taxes revert to the original taxing authorities such as the city and the Denver Public Schools. Such financing was buttressed by Forest City loans. Overall, the project was to be developed without direct city funding.

How the Green Book Vision Turned Out

How the Green Book Vision Turned Out

“Wow! Stapleton has succeeded beyond my wildest dreams.” —Happy Haynes

“Now you have tens of thousands of young families opting to live in Stapleton. That’s a good problem to have. It’s not a problem Denver had in the ’70s or ’80s.” —Tom Gougeon

In 15 years, Stapleton has achieved 61 percent residential build-out, much of the “trunk” (regional) open space, most of the parks and pools associated with neighborhood development, retail square footage far beyond the Green Book vision, significant industrial development, and limited office development. Major and local streets are generally in place and funding has been acquired for the MLK Boulevard extension to Peoria Street in 2016. In addition to the elementary and middle schools anticipated by the Green Book, a high school is now open.

Surprises Along the Way

“You’d be naive to think that you can predict 20 and 30 years of future development activity in the metropolitan area, right? Everybody clearly recognized that, and that’s why that document was not meant to be prescriptive but a guide.” —Jim Chrisman

As CEO of the Stapleton Foundation, Haddon refers to her organization’s focus on education, wellness, environment and affordability/diversity as the Green Book’s “heart and soul.”

That flexibility has allowed room for real arguments over project specifics; for example, whether an Eastbridge commercial site anchored by a large format store (King Soopers) is consistent with the Green Book vision of urban villages. And Forest City’s performance relative to affordable housing is an unfinished story. On that score, David Netz, the current CAB co-chair, says that the group’s year-end report will for the first time include a build-out scenario, including Section 10 (north of 56th Ave.), that will attempt to assess whether land-banking by Forest City will be sufficient to allow them to eventually meet their affordable housing goals.

The Green Book vision hit the mark on housing and parks, but in retrospect it didn’t foresee market forces in several areas:

Retail space. The Green Book did not address the issue that northeast Denver was grossly underserved. This put pressure on Forest City to provide regional retail, a decision that helped generate tax revenues needed for project infrastructure.

Mayor Michael Hancock says, “If we’re going to achieve the vision of a diverse community, housing has to lead the way.”

Four of the principal authors of the Green Book gather to reflect on a vision being implemented. Left to right: Beth Conover, Tom Gougeon, Jim Chrisman, Alan Brown.

School-age population. The market for housing in Stapleton was so unknown 25 years ago that planners assumed Stapleton’s average household size would match the city’s. DPS says in 2013 Stapleton had three times the city’s average in number of students per single family home. This led to an accelerated need for schools and reallocating funds between schools and parks.

School-age population. The market for housing in Stapleton was so unknown 25 years ago that planners assumed Stapleton’s average household size would match the city’s. DPS says in 2013 Stapleton had three times the city’s average in number of students per single family home. This led to an accelerated need for schools and reallocating funds between schools and parks.

Office space. Even apart from the Great Recession, the demand for envisioned office space has been very slow in coming.

Fitzsimons/Anschutz redevelopment. The closing of the former Fitzsimons army base was not mentioned in the Green Book and even those familiar with Fitzsimons have been surprised at how quickly the medical/research campus has been redeveloped. Fitzsimons has greatly benefited Stapleton by becoming its de facto office park.

Looking Forward

The Eastbridge Town Center and the Aurora residential and park development are expected to break ground in 2016. Other developments and improvements will happen but on less certain timelines:

- Section 10, a one-square-mile parcel north of 56th Ave., will include nearly 2,500 dwellings.

- The 34-acre transit oriented development (TOD) site just south of the Central Park Boulevard commuter rail station where service will begin in the spring. CAB members have expressed the view that this is an appropriate location for affordable housing. Jim Chrisman of Forest City says this site is currently consuming the major part of the company’s marketing time.

- Additional office and industrial development near the I-70 corridor.

- Completion of trunk open space and trails.

- Future use of Stapleton land near Peoria and 25th Ave. has not been determined. The best guess now is it may become a mixed-use area.

Is the Green Book a living, functioning document? “The people working on it in the early days had the freedom to say what it should be,” says Gougeon. “Now when all these people move in, you can’t tell them that they don’t get to define any of the goals. I think there’s always been a balance of the founders versus the real residents, finding a way that achieves everybody’s broad objective.”

The city says SDC and CAB will sunset when all land has been transferred from DIA. CAB chair David Netz says as long as planning and development of major filings proceeds, the CAB expects to continue representing the larger community’s interest in seeing the vision achieved. Jim Wagenlander, suggests that the city formally review the 20-year-old document just as it would regularly update any comprehensive plan: “If not updated and not understood, it’s an empty guide.” SUN President Mark Mehringer says that the “Green Book principles that drew people here in the first place are not as strong as earlier, and if it’s going to impact the community in the future, someone will need to keep people educated about it.”

The city says SDC and CAB will sunset when all land has been transferred from DIA. CAB chair David Netz says as long as planning and development of major filings proceeds, the CAB expects to continue representing the larger community’s interest in seeing the vision achieved. Jim Wagenlander, suggests that the city formally review the 20-year-old document just as it would regularly update any comprehensive plan: “If not updated and not understood, it’s an empty guide.” SUN President Mark Mehringer says that the “Green Book principles that drew people here in the first place are not as strong as earlier, and if it’s going to impact the community in the future, someone will need to keep people educated about it.”

That someone may be the Stapleton Foundation, which will be funded in perpetuity by a real estate transfer fee on home re-sales in Stapleton. CEO Bev Haddon says the foundation will focus more tightly on the goals of affordable housing and diversity now that the school, wellness and environmental initiatives are well underway.

Relative to the spirit of the Green Book, diversity and affordable housing are the remaining issues. The Green Book speaks in general terms about creating “diverse neighborhoods.” Its recommended housing policies call for a “variety of housing types and densities” for all income levels. The policy section also includes these statements: “emphasize housing for middle income families” and “attract high end housing.” In this, Stapleton has been a roaring success, much to the surprise of the early planners. For example, Stapleton incomes are more than twice the Denver average. But racially, relative to Denver as a whole, whites are overrepresented, and Blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented.

Hancock and others have expressed concerns about the perception that Stapleton is, in effect, a gated community without gates, though he says seven of every 10 Stapleton residents he’s met say they want to live in a diverse community. He notes Stapleton’s success in the education realm and expressed his hope that young people with different attitudes will lead the way to a more integrated future.

Community leaders who otherwise praise Stapleton express concerns with this aspect of the Green Book. For Happy Haynes, the issue of diversity “gnaws” at her. Ever the optimist, Mayor Hancock says the city wants to “make sure that we help affordable housing come to every TOD. Stapleton’s no different.”

CAB chair David Netz puts it this way: “Stapleton is the largest chunk of city-owned land where affordable housing is built in as part of the development agreement. If we can’t do it here, where could it be done?”

1 Stapleton: An Oral History, Compiled by Robin Chotzinoff, The Stapleton Foundation, 2015

Note to readers: The Stapleton Development Corporation currently has vacancies on their board. Click here for more information.

0 Comments