During our 45th mayor’s inauguration speech this past July, Michael Hancock spoke about the “153-year marathon journey” that has led the city of Denver to her present-day greatness. His vision for a 21st-century Denver includes a bustling “aerotropolis” that would envelop Denver International Airport. As Hancock foresees it, the multipurpose airport city would become a “regional economic powerhouse” and pilot growth in northeast Denver.

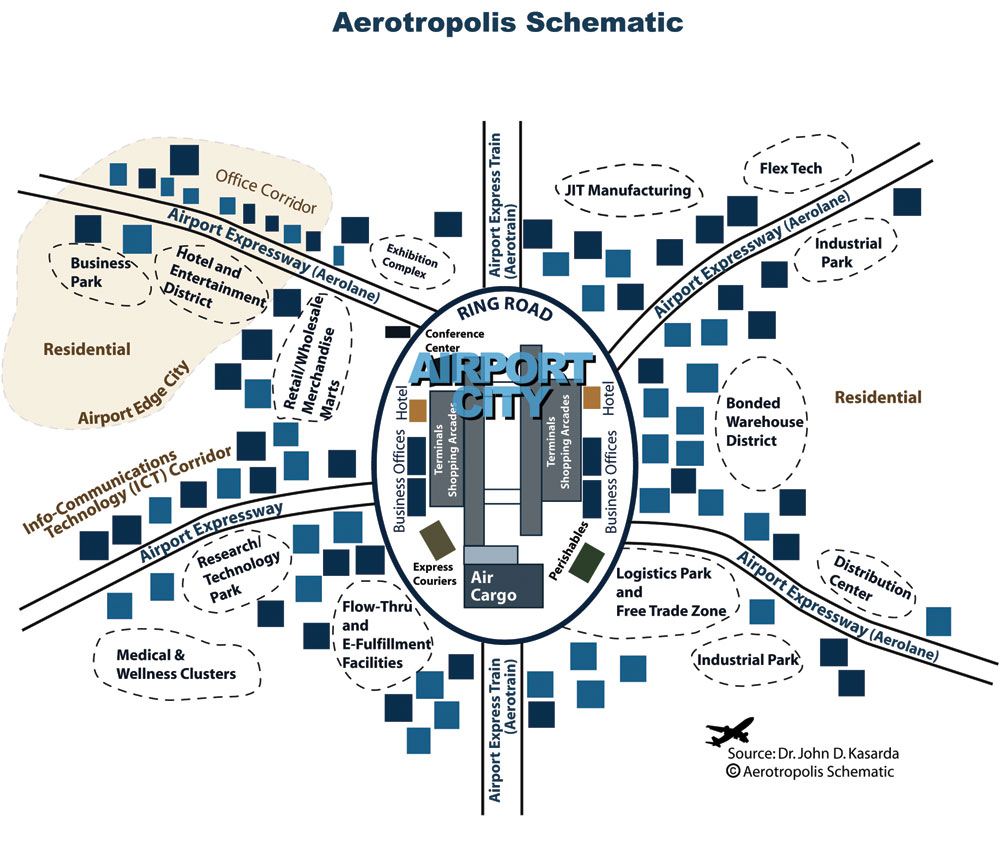

Hancock has embraced the aerotropolis concept that has been championed around the globe since 2000 by Dr. John Kasarda, who works with regional municipalities and countries to help them leverage their airports and surrounding landscapes to catalyze economic growth. Kasarda views today’s airports as “powerful economic engines” that can attract all types of aviation-linked businesses: “As economies become increasingly globalized…air commerce and the speed and agility that it provides to the movement of professionals and high-value goods become an economy’s logistical backbone.”

Mayor Michael Hancock (below left) and Dr. John Kasarda (far below right), considered the father of the aerotropolis concept, were interviewed by the Front Porch to help readers understand what an aerotropolis is and what it would mean for Denver. Photo of DIA was taken at the groundbreaking for RTD’s East Rail Line in July 2011.

Mayor Hancock describes the aerotropolis as “an opportunity to attract a lot of industries that thrive off their closeness to the global markets and their ability to access them conveniently.” But beyond those industries, the aerotropolis offers the opportunity to attract a cluster of other industries that are part of the supply chain. “For example,” says Hancock, “SMA at Stapleton [the German company that produces solar inverters] has been responsible for no fewer than five new companies that have moved to Denver because they’re part of SMA’s supply chain. That’s important stuff when it comes to developing a cluster.

Mayor Hancock describes the aerotropolis as “an opportunity to attract a lot of industries that thrive off their closeness to the global markets and their ability to access them conveniently.” But beyond those industries, the aerotropolis offers the opportunity to attract a cluster of other industries that are part of the supply chain. “For example,” says Hancock, “SMA at Stapleton [the German company that produces solar inverters] has been responsible for no fewer than five new companies that have moved to Denver because they’re part of SMA’s supply chain. That’s important stuff when it comes to developing a cluster.

“There are two things you’re trying to do,” explains Hancock. “Attract new companies to try to create a cluster, and then attract companies that will thrive because they’re part of that cluster and that corporate-communal activity. For example, in Dallas-Fort Worth they created an aerotropolis and the finance industry initially was not their target. But finance became a driving force in the creation of the aerotropolis and a cluster around finance developed around the airport. There are going to be some unexpected things.”

Hancock cites examples of industries Denver might pursue to create clusters: “Biosciences, bioscience devices, so medical equipment being sold and shipped out of Denver, or manufactured. Manufacturing is a new and big area that we are really focused on. Aviation, aerospace, clean energy.”

In his recent trip to Japan, Hancock says the largest land-developing company in the country asked for a presentation of the aerotropolis that they’d heard about.

“But the first step,” Hancock continues, “is to come up with a master plan to develop the area and see where it goes from there. We can predict what kind of clusters we might want to drive out there but the market will dictate that. It’s about, ‘We have land, we want to develop it, we’ve got to have a vision for what it might look like infrastructurally. What is the branding of this area of town?’ Those are the kinds of things that help drive initial interest and investment.

And sustainable, green communities will “absolutely” be a requirement in the development of the aerotropolis, says Hancock.

The early steps have started through the DIA planning process, reaching out to Aurora, Adams County, Commerce City and Brighton. Hancock says all the areas that are touched by the aerotropolis have been contacted to give their input.

How does the development of an aerotropolis affect Stapleton? Jim Chrisman, senior vice president, Forest City Stapleton, says, “Stapleton can be considered as one of the first phases of the aerotropolis, given its proximity to the airport. We hear anecdotally that there are many residents that chose Stapleton partly because of its easy access to the airport and we believe the same to be true for some of our businesses, such as SMA America, the producer of solar inverters, for example, which benefits from the direct flights to Germany.”

Dr. Kasarda believes that if a DIA aerotropolis can lure high-technology manufacturing enterprises, for example, biomedical or electronic, then office, retail, entertainment, hotel, trade and convention complexes, even housing would follow, and fill in the airport metropolis. One premise of the aerotropolis proposition is that an airport can serve not only travelers, but also locals who work within and outside the airport. They would need to travel only a few minutes from their respective workplaces to shop, eat and recreate, just like their inner-city counterparts do. Regional transportation systems like the emerging FasTrack East Corridor could also deliver thousands of consumers from nearby neighborhoods to the DIA aerotropolis.

Kasarda suggests that Mayor Hancock look to Amsterdam’s Schiphol International Airport as a role model for DIA’s aerotropolis. “Schiphol is Europe’s fifth-busiest airport with 45 million passengers traveling through it annually. Nearly 60,000 people are employed on the airport grounds. Its passenger terminal operates as a suburban mall, complete with a full-service grocery store that is accessible to both travelers, airport-area employees and local residents.

“Across from the passenger terminal is the airport’s World Trade Center and the regional headquarters of Unilever, a multinational consumer products company, and the electronics and defense giant, Thomson-CFS. Five-star hotels adjoin the Trade Center. Within walking distance is a world-class office building campus that houses businesses that serve the aviation industry. Business parks line several highways that lead to the airport with hundreds of corporations that leverage their proximity to the airport.”

With much of DIA’s 53 square miles of surrounding land still undeveloped, Kasarda views DIA as an ideal candidate airport for the first U.S. aerotropolis built from the ground up. DIA is the third-largest international airport in the world (in land area) and has the longest public runway in America. It had over 20,600,000 passengers in the past year and has the capacity to accommodate 50 million passengers per year. He says the key to Denver’s success is, “The City of Denver must get their planning of an aerotropolis right. If there is not appropriate planning, airport-area development will be haphazard, economically inefficient, and unsustainable.” He added, “The aerotropolis model brings together airport planning, urban and regional planning, and business-site planning, to create a new urban form that is highly competitive, attractive and sustainable.”

Dr. John Kasarda is a Kenan Distinguished Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship and director of the Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flager Business School. He will chair the 2012 Airport Cities World Conference to be held in Denver in April.

0 Comments