Joslyn Ford-Keel of DIME Denver sings Lift Every Voice and Sing at the City Park event preceding the 35th annual Martin Luther King, Jr. parade (“Marade”) on Jan. 20, 2020. The MLK event at City Park prior to the Marade was attended by elected officials including, behind singer Joslyn Ford-Keel (from left): Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman, U.S. Representative Ed Perlmutter, Gov. Jared Polis and Denver Mayor Michael Hancock. Front Porch photo by Christie Gosch

If you know the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” you’re most likely Black—and you also know it is often referred to as the Black National Anthem. If you’re White, you likely know none of the above.

Dr. Claudette Sweet’s signature song is Lift Every Voice and Sing, which she sings here a capella from a pew in Zion Baptist Church. Zion, the oldest African American church in the Rocky Mountain West, was established a few months after the Civil War ended in 1865. Front Porch photo by Steve Larson

To hear Dr. Claudette Sweet sing Lift Every Voice, click here

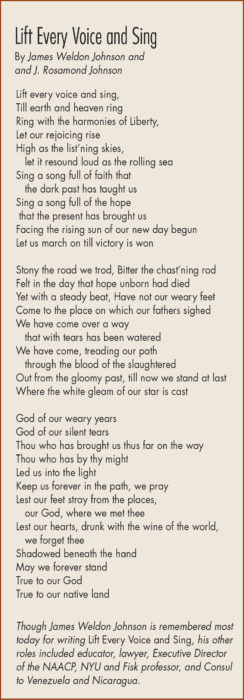

James Weldon Johnson penned the poem, Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing in 1899. Composer John Rosamond Johnson, his brother, set the words to music, and in 1919 the NAACP adopted it as its official song, dubbing it the “Negro national anthem.” Front Porch spoke to three generations of NE Denver neighbors to explore its meaning 120 years later, and its sometimes-controversial characterization as the “Black National Anthem.”

NE Neighbors’ Recollections of Lift Every Voice from the 40s to the 90s

Rev. Dr. Timothy Tyler and Dr. Nita Mosby Tyler of Shorter Community AME Church affirm the significance of Lift Every Voice and Sing, as well as the Star-Spangled Banner. Rev. Tyler says, “One song is incomplete without the other.” Front Porch photo by Steve Larson

Park Hill resident Dr. Claudette Sweet, a retired DPS literacy educator, received her education in the segregated schools of Beaumont, Texas in the 1940s and 50s. Sweet credits her mother and her teachers with instilling in her a love of music and African American culture and history. A mezzo-soprano, she shares insights on the song’s correct performance, including shifts in its timing with each stanza. She recalls being “really shocked” when she moved to Denver in the 1960s: “The people in the churches here in the North, they did not know that this song was the Black national anthem.” To hear Dr. Claudette Sweet sing Lift Every Voice, click here

Dr. Nita Mosby Tyler grew up in Atlanta in the 60s and 70s, where she attended the Baptist church led by Dr. Ralph David Abernathy, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s close friend and advisor. “The song absolutely had great prominence on all kinds of levels for us in the church. It was a part of our hymnal and Rev. Abernathy always said pretty explicitly: ‘We’re not going to wait until Black History Month to sing this song. We’re always going to sing this song.’” Tyler is the founder of The Equity Project, First Lady of Denver’s Shorter Community AME Church, and Board Chair for the Denver Foundation.

Camille Osbourne-Roberts, a Stapleton parent of two, attended schools in central Los Angeles that were desegregated in name but were predominantly Black during the 80s and 90s. In first and second grade, “The books that we read and the lessons we learned were all geared toward self-pride.” Here she learned Lift Every Voice and Sing, which students sang after reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. Though she thinks Blacks are “expected to know” the song, she recalls a Black fraternal organization’s event a few years ago, where voices dimmed as the song progressed past the first stanza, as fewer people knew the words.

Bishop Jerry Demmer, President of the Greater Denver Metropolitan Ministerial Alliance, speaks at the Martin Luther King, Jr. annual event in City Park before Denver’s 2020 Marade. Front Porch photo by Christie Gosch

Is it really a Second National Anthem?

Is it really a Second National Anthem?

Though Lift Every Voice and Sing—which has been performed by singers as diverse as Beyoncé and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir—continues to be referred to as the “Black national anthem” by many, others take issue with the moniker, which they see as divisive. Ultimately, however, the song resonates so powerfully not only because of its message of overcoming adversity and achieving excellence, but because, as Dr. Nita says, it speaks to African Americans’ “lived experience.”

Rev. Dr. Timothy Tyler, pastor of Shorter Community AME, says the song speaks to “the common experience of human suffering. There’s so much power in the Black story that it really speaks to anyone who has gone from the bottom and through traumatic odds and has been able to rise despite suffering.” But he also embraces it as specific to Black Americans’ experience and history: “We celebrate it and…I don’t think that our story should ever be separated from the American story. I just think that it [African-Americans’ story] is never included in America’s story; in fact, I think it is the foundation of the American story…and I think it’s important to characterize it [the song] as the Black national anthem.”

“There are pieces of our country’s national anthem that in many ways contradict what the Black national anthem talks about…it is the same flag that felt fine with slavery and the oppression of Black people in America—and so that sort of contradiction…gets talked about in the Black national anthem,” says Dr. Nita.

Like the Tylers, Sweet recalls the song typically being paired with the Pledge of Allegiance and the Star-Spangled Banner. Sweet says her teachers emphasized both pride in Black history and the nation, despite the country’s failings during an era when she was banned from even trying on clothes in a Denver department store due to her race. Sweet says, “If you will interpret the lyrics of the Star-Spangled Banner, you find it is pretty violent. I think our song is much more peaceful…the Star-Spangled Banner, we respect it…I will always sing it because it is a part of my upbringing.” She will not, however, sing the deeply problematic third stanza, which says in part “No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.”

The MLK Marade on January 20 started with a program at the Martin Luther King Jr. statue in City Park. Also on the monument are Ghandi (left) and Rosa Parks. Front Porch photo by Christie Gosch

Both Sweet and Osbourne-Roberts share their wish that schools today would instill greater knowledge of Black history and cultural pride. Osbourne-Roberts shares her disappointment over the resounding silence on Black history in her children’s curriculum across several DPS schools. She is intentional in educating her children on that history, including Lift Every Voice and Sing, and observes that the Black history that is taught centers on Martin Luther King, Jr., to the exclusion of all others. “It’s so much more complicated than that,” she says.

Lift Every Voice ends with “true to our native land.” It evokes patriotism while recognizing the hybrid identity many African Americans experience. Osbourne-Roberts says she’s shifted her focus in recent years from July 4th to celebrating Juneteenth, popularly associated with the end of slavery in Texas. With the flag now being used by many as a symbol of nationalism rather than patriotism, “I feel it is taking on new meaning that I can’t get behind,” she says.

Both Osbourne-Roberts and Rev. Tyler reflect on a popular YouTube video that uses Lift Every Voice to accompany images from African-American history. As the song reaches its crescendo, a clip shows President Obama coming onto a stage. Rev. Tyler says in the past people would cheer, but “Now when we play that video, you don’t have as much cheering…What we used to think was accomplishment, it feels like we have gone backwards—so I think it [the song] almost has a new energy in a different way.” For Dr. Sweet, however, Lift Every Voice is meant to uplift all Americans, and she focuses on its hope for a brighter future.

I am 72 and white. I have known of this song since I was a teenager. I bought a 45 rpm of it by Kim Weston back in 1970 and appreciated it then and now. Recognizing this song is what inclusivity is all about. When I was in grade school we sang “Oh Beautiful” rather than the “Star Spangled Banner” and later “This is My Country” and no one made a fuss. We shouldn’t be upset that there is a black national anthem, we should be upset that one was needed.

The past is the past and our history which people have been destroying and bad mouthing I am not a prejudice man but I don’t believe in destroying our history good or bad let’s look to the future for our children’s and families sake .yes I had family in the Confederate army that’s my family heritage and taking down our statues and criticizing the Confederate flag will only make things worse for everyone so please can we stop this s**t but honestly if you want to take our history how would NAACP like it if someone took down the MLK statues and pictures he was a great man but he was in the past I have to admit what is good for the goose is good for the gander so let’s take all the statues and close all the museum’s then what would we have to complain about but truthfully we need to look to God and forget about the past and live for the future that is my opinion I guess we still have freedom of speech or are you going to take that away just like history

They suggest that you can’t say God… But enforcing integrity Humanity admit the special gift that we can share with each other that blessing is a miracle… Lifting someone up on the journey in their Adventure of life and individuality can truly make a difference… at the end of the day music is something we can all relate to the message is something that we share show that message with Direction show that message with heart… lift every heart and sing let that be the allegiance