![]()

This photo of Abbye was snapped moments before lightning struck nearby. Electrical charges in the atmosphere before a lightning strike can raise hair into the air. It may look funny, but is a serious warning.

On June 28, my good friend Abbye Neel and I hiked Mount Bierstadt, which summits at 14,060 feet. Bierstadt attracts many hikers because of its short drive from Denver and manageable climb. This was not the first fourteener for either of us, but we made the novice mistake of starting late—at nearly 9:30am. Hikers should summit a fourteener by 11am, according to the National Forest Service. It will be fine, we thought. We wore the right clothes, had plenty of water, packed snacks, sunscreen, rain jackets, first aid, and, of course, checked the weather—blue skies with possible thunderstorms in the late afternoon.

After almost two hours we had made it halfway up our ascent and emerged onto a ridge with views of the Front Range in every direction.

A view from a great height is irresistible, almost spiritual. Things look and feel different. Details become less visible and the big picture becomes more visible. This is why I choose to enjoy Colorado’s fourteeners.

But the views were cut short. In a matter of three minutes, a dark cloud swallowed up the blue sky and we realized our hair was standing straight up. We laughed. How ridiculous looking! It was reminiscent of a time as a kid with my family on the summit of Pikes Peak. It was hailing and our hair stood up. Our umbrella buzzed when raised into the air and we laughed, feeling like Benjamin Franklin—frightening to think of now. Buzzing means the object is beginning to conduct electricity. Metal objects like an umbrella can attract lightning if it strikes nearby. The electricity can flow through the object and superheat it, causing severe burns. After awhile we got in the car and drove off, not knowing we dodged a potentially volatile situation.

This time I knew the hair-raising warning meant the air was electrically charged, but how dangerous was it? At what point does a hiker turn around? Other hikers on the trail considered whether or not to continue. Then the storms hit. Lightning ripped through the air directly parallel across the ridge less than a mile away. Now the answer was clear, and out of instinct we ran. It smelled like burning, which we later found out is the ozone, and it started to hail.

Thankfully, we were able to make it to a lower elevation without being hurt. Meanwhile at the summit, it was chaos. Fifteen people were at the summit when lightning struck and three had been badly affected, including Jonathan Hardman.

This is the last photo Jonathan Hardman and his dog, Rambo, took together. Shortly after beginning their decent they were struck by lightning 200 feet from the summit and Rambo was killed. (Photos provided by Jonathan Hardman)

Hardman, 27, started his hike at 7am with two friends and his 7-month-old German shepherd, Rambo. Hardman, a Wisconsin native and Colorado resident for three years, has hiked many fourteeners and could be considered over-prepared—he hiked with an extra pair of shoes in his pack. Why? Just in case, he says. It was sunny the entire ascent and he even took off his shirt it was so hot. The group summited by 11am and began their descent as soon as the clouds looked slightly unpredictable, but by that time it was too late. Lightning struck but didn’t hit the people at the top. It traveled 200 feet below the summit to where Hardman was crossing a boulder field. He felt an intense pain and was knocked unconscious, falling onto his face in the rocks. He awoke later with no feeling in his arms or legs and his ears ringing. He was confused and saw that Rambo had died.

“I just screamed ‘No’ and ‘Rambo.’ It was like a nightmare,” he said.

Hardman is one of 39 people who have been struck by lightning in Colorado since May this year, according to Chaffee County. There has been one death, a 32-year-old woman who was hiking Mount Yale on July 17 with her husband. They married less than a week before.

Because of climate change, there have been an unusual number of thunderstorms in the state and it’s predicted that in 50 years there will be two to three times more lightning, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Lightning may seem supernatural and be entertaining to watch, but it is no laughing matter and should be taken seriously, especially by those who choose to hike Colorado’s highest peaks.

“Lightning is a cultural icon. For some it is something to fear, something to be amused by, or something to observe without any personal danger, but no matter whether we’re talking about an oil refinery or a golf course or the trail up to Mount Bierstadt, the fundamental of lightning is that no place outside is safe and no place outside can be made safe,” says Richard Kithil, founder and CEO of the National Lightning Safety Institute in Louisville, Colo.

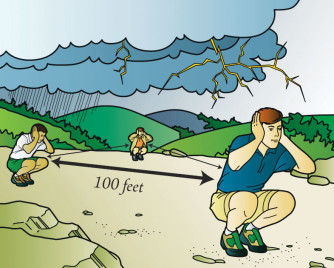

In a situation where it’s not possible to quickly get to lower elevation, crouch down 100 feet apart and cover your ears. Stand on the balls of the feet to touch as little of the ground as possible. (Graphic provided by Boy Scouts of America)

For the most part, lightning safety in any scenario requires recognizing risk and not waiting until it actually strikes to get to safety. If you can hear thunder, the loud shock wave from an electrical discharge, lightning is 3–8 miles away and hikers need to turn around. If hikers are caught in a situation where they can’t get to a lower elevation quickly, as a last resort spread out 100 feet from each other and crouch over with hands covering ears and stand on the balls of the feet to touch as little of the ground as possible. The ground, especially rocks, is a great conductor of electricity. This is why animals more than people die from lightning because their four limbs provide four entry points for the electrical current. In 1999, fifty-six elk were killed on Mount Evans from a single lightning strike.

Despite signs on trails, campaigns for lightning safety by organizations like NOAA, stories in the news, and even thunder, many people still go into dangerous situations. After Hardman was struck, evacuation helicopters couldn’t make it to the summit due to the weather so other hikers helped him down the mountain. Along the way, people going up the trail passed him by, disregarding the weather and his obvious injuries. “Many have the mentality ‘it can’t happen to me,’ the same self-imposed mentality that they can drive through a red light and they wouldn’t get hit,” Kithil says.

But everyone has an intuitive sense of danger. People just don’t always listen—or they replace intuition with lightning detector gadgets from outdoor retailers that often inaccurately predict the weather. Change the subject from lightning to rattlesnakes, and suddenly everyone has a built-in sense of danger. Kithil wants people to have that same intuition with lightning.

While some may knowingly go into dangerous situations, others are prepared and caught in unfortunate situations, like Hardman. Weather, especially at high elevations, can change without warning. “I don’t know how I would’ve prepared better—maybe left (behind) the extra shoes. It was just a freak situation. If I had felt uneasy I would’ve turned around,” he says.

After being struck by lightning and falling on his face into boulders, Jonathan Hardman was taken to St. Anthony Hospital. Emergency physicians weren’t sure whether Hardman was directly struck until they saw the distinctive pink markings called the Lichtenberg figure only seen in lightning victims.

After making it down to the trailhead, Hardman was taken to St. Anthony Hospital. His heart rate was not steady; it fluctuated 60 beats from one minute to the next. Along his neck he had the Lichtenberg figure, sometimes called ferning or lightning flowers. The pinkish branch-like markings appear when the high electrical current damages the capillaries underneath the skin, according to the National Lightning Safety Institute. The marks appear within an hour after being struck and completely fade after a day or two. This is only seen in people who are struck by lightning, although a person can be affected by lightning and not have the marks.

Hardman could not wait to get another dog and returned to the same breeder, shown here, where he got Rambo only seven months earlier. In a stroke of fate, they happened to have one of Rambo’s little brothers, which Hardman named Blitz, German for lightning.

Ninety percent of lightning victims survive. Hardman has experienced typical symptoms for the victim of a lightning strike: extreme muscle aches, headaches, dizziness, and short-term memory loss. How lightning affects the brain has vexed neurologists. They treat lightning injuries similarly to traumatic brain injuries.

Now a little more than a month later, Hardman has knee and back pain but generally feels better physically and mentally, although he’s noticed he’s more emotional. Most of all, he misses Rambo. At the end of July, he went for a hike and spread his ashes at the top. In early August, he will go to the same breeder and pick up his new puppy, Rambo’s brother, who he named Blitz, or German for lightning. “Colorado has been good to me. I’m going to continue hiking. My only advice to people is trust yourself. You can bring all the right equipment but you need to check the sky and trust yourself that if you feel unsafe you probably are. You can do everything right and this can still happen.”

To learn more about lightning safety, visit lightningsafety.com or lightningsafety.noaa.gov.

0 Comments