As part of an injury awareness and prevention program, emergency medical technicians at the University of Colorado Hospital describe in very personal terms how it feels to be the first on the scene when teenagers are involved in serious automobile crashes.

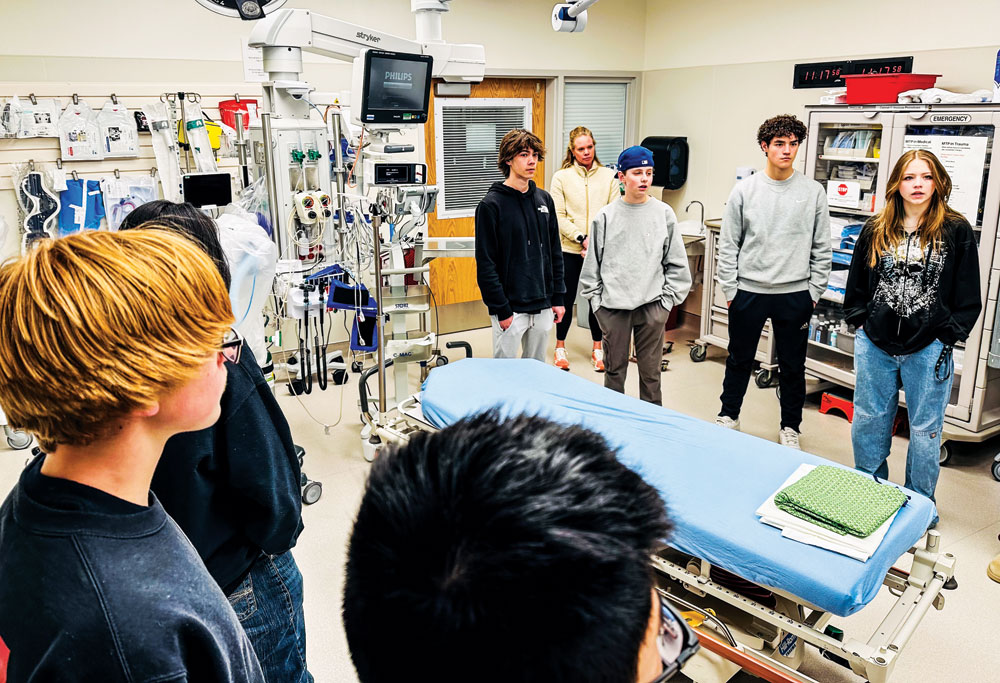

On a recent Saturday morning, a group of 15 Denver teens listened as emergency medical technicians talked about what it feels like to be the first on the scene of a car crash—especially when it involves young people. Later, the students spent time in a UCHealth emergency room and a burn unit. They heard from a woman whose husband was biking when he was killed by a drunk driver. And they ended the day by role playing what it is like to deal with paralysis or serious head injuries.

Laurie Lovedale, program manager for injury prevention at University of Colorado Hospital, explains how teens impaired by alcohol or drugs could end up with injuries that have to be treated in the burn unit.

It was all part of an injury awareness and prevention program called Prevent Alcohol and Risk-Related Trauma in Youth (P.A.R.T.Y.). “The idea is to get high school students to think about the choices they make when they’re in a vehicle and how those choices always affect far more people than just themselves,” says Laurie Lovedale, program manager for injury prevention at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital.

There’s good reason to try to change teen behaviors behind the wheel. In the U.S., the fatal crash rate for 16-19-year-old drivers is three times the rate for drivers over 20, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Of all fatal crashes in 2021, half of the 16- to 19-year-old drivers were not wearing seatbelts. The P.A.R.T.Y. program, which was started in Canada in 1986, is designed to change risky behaviors and reduce those grim statistics.

Since 2008, UCHealth has been offering the program free of charge to school groups. Four or five times a month, Lovedale meets with groups of teens and starts with the basics: the importance of wearing seatbelts and why texting and driving don’t mix. “Our brains can’t multi-task. They cannot do two thinking things at once,” says Lovedale. “And driving is always going to become secondary to manipulating a phone.”

After that initial briefing, Lovedale takes the students on a trauma patient’s journey through the hospital so they can better understand the ripple effect when someone is involved in an auto crash. After they meet with the first responders, they go to the emergency department. “We want them to see how many people are in a trauma bay trying to save a life. That’s always an eye-opener for the students.” The teens roleplay being the attending physician, the nurse, the resident, or the respiratory therapist. “You know, potentially there are 12 or 14 people in there impacted by your negative choice,” says Lovedale.

Laurie Lovedale, program manager for injury prevention at University of Colorado Hospital, explains how teens impaired by alcohol or drugs could end up with injuries that have to be treated in the burn unit.

Although Lovedale usually works with high school teachers or counselors who seek out the program for their students, this recent event was organized by Central Park mom Sarah Stabio. She says she was particularly interested in the program because she had an uncle who died at age 18 in a car crash. “He wasn’t the driver and he wasn’t drinking, but the driver was. It was after a graduation party. This was a couple of months before I was born, so I never got to meet my uncle,” says Stabio.

After watching the program in action, she said she was impressed. “I know it’s not a silver bullet, but I do think you have to keep reinforcing these messages for your teens. And to hear from these trusted sources at UCHealth, I just think it’s very valuable.” Her 15-year-old son Oliver said one big takeaway he got was how important it is to wear seatbelts. Even when crashing at a higher speed, “a driver wearing a seatbelt has a much higher chance of survival,” says Oliver Stabio.

Lovedale says her team conducts pre and post surveys, including anonymous surveys 4–6 weeks after the class to determine whether teens have changed their behaviors, like wearing seatbelts or avoiding checking their phones. But she says hard data measuring those changes is difficult and expensive to collect. Several studies done in Australia and Canada indicate that teens who have participated in the one-day program are involved in fewer car accidents, but no such study has been conducted in the U.S.

In focus groups after the classes, Lovedale says participants indicate they like hearing the personal stories about people who have been impacted by auto crashes, and they say it’s powerful when state troopers show photos of local car crashes where teen drivers had been involved. “We don’t sugar coat things, and they seem to appreciate that,” says Lovedale. She is also quick to add that the program doesn’t just focus on negative behaviors. “We also try to show what a positive ripple looks like. If you’re the driver, make everybody wear a seatbelt, or if you’re the passenger, how can you help the driver be less distracted?”

Parents, teachers, or counselors who are interested in scheduling a P.A.R.T.Y. workshop should email laurie.lovedale@uchealth.org.

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments