Long-time Park Hill residents and close friends, Helen Wolcott (left) and Anna Jo Haynes (right) reminisce about life in Park Hill during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Both were major figures in Denver’s integration.

“Throughout history, neighborhoods have shifted from predominately one race to another. Some go from white to black to white again,” says Denver historian and author, Phil Goodstein.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Five Points was known as the “Harlem of the West,” where prosperous black doctors, lawyers, dentists and clergy lived, according to the Five Points Business District History. It became a thriving cultural arts district with more than 50 bars and clubs, where jazz musicians such as Billie Holiday and Duke Ellington performed. Real estate companies, drug stores, religious organizations, tailors, restaurants and barbers provided goods and services for the black residents.

After World War II, Denver had a large influx of African Americans. Many were GIs who had trained or been stationed at Lowry Field, Buckley Field, Fort Logan, Fitzsimons Army Hospital, Camp Carson or Camp Hale. After the war ended, they returned to Colorado to settle and raise their families. Many sought defense jobs at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal.

Many of the new African Americans settled in Five Points because the neighborhood was considered open to blacks at that time, but there wasn’t enough housing to support the influx. Houses were scraped and turned into multiple smaller houses or apartments. The shortage of housing led to overcrowding, dilapidation and crime. In the late ’50s and early ’60s many African Americans moved out, known as “black flight.”

Helen Wolcott (left) and Anna Jo Haynes (right) stand along 26th Avenue. African Americans were refused home loans for houses south of 26th, where predominately white people lived. Wolcott and Haynes fought for Fair Housing and an integrated neighborhood.

When African Americans started moving into Park Hill in 1960, white residents put their homes up for sale in fear of a “black invasion.”

African Americans unfortunately couldn’t move wherever they wanted, though. The Colorado State Fair Housing Act of 1957 made it unlawful to discriminate in the sale, rental or financing of housing based on race, religion, sex, nationality or ancestry. But there was one major loophole—it excluded homeowners who were still living in their home. Basically, a person could sell or not sell to whomever they wanted.

Realtors wouldn’t show homes to black people in predominately white neighborhoods. Landlords told African Americans, “I’m sorry, the apartment was just rented,” and then rented it to a white family later that day.

Plus, banks did not finance home loans for African Americans interested in older nice neighborhoods, a practice known as redlining. Banks literally drew red lines around neighborhoods where they would not invest and/or around neighborhoods where they would not offer loans to minorities.

But gradually throughout the 1950s, African Americans who could afford it moved farther and farther east seeking better homes and schools. Originally, the farthest east black people lived was Downing St. Then in 1954, Manual High School was built, and African Americans moved farther east to York St.

Sandra Dillard, an African American and founder of the National Association of Black Journalists, lived from 1952–1970 at 2510 Vine, one block west of York. Her family was the first African American family on the block. She says a neighbor poisoned her mother’s dog after they moved in. “We didn’t bother anybody, just went to school and came home,” Dillard says.

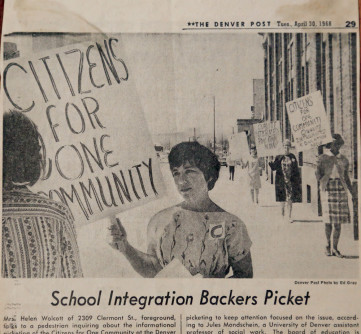

Helen Wolcott talks to a pedestrian about school integration outside the Denver School Administration Building in 1968. She and fellow picketers demanded DPS put together a plan for integration.

In the late ’50s, the line where black families lived was Colorado Blvd., just across the street from Park Hill, historically the white, affluent community. With tall trees, big homes, good schools and nearby libraries, Park Hill had become the ideal neighborhood in Denver.

Colorado Blvd. acted as a type of Mason-Dixon line to separate blacks from the upper crust of Denver. But in 1960, African Americans who could afford Park Hill homes and found progressive realtors made the jump. “It was of the utmost prestige to cross Colorado Blvd. as an African American,” Goodstein says.

As the number of African Americans in Park Hill increased, a surprising change happened. Realtors saw an opportunity to make money. While they had previously done everything to keep blacks out, now they wanted blacks to move in. “They wanted the wealthy African Americans to move in and transition it to a black neighborhood,” Goodstein says.

When a black person moved into a block, realtors called the other white residents and warned about a “black invasion.” “You better get out while you still can, they’d say,” according to Helen Wolcott, who’s lived at 2309 Clermont since 1961. “They called weekly asking us to list our home.”

For Sale signs popped up like weeds. The fearful white people fled in masses, known as “white flight.”

In 1961, thirty residents, including Wolcott, met at Montview Presbyterian Church and formed the Park Hill Action Committee, Inc. (PHAC). Their goals were to maintain Park Hill as one of the finest neighborhoods in Denver, and find a solution to the fear and prejudice around integration. Wolcott firmly believed integration was the morally right thing to do. She grew up in a wealthy Jewish neighborhood in Kansas City. She loved her black nannies as her real mothers. It wasn’t until she started reading authors like James Baldwin that she knew civil rights existed and recognized the racism she grew up in. She vowed her children would have different childhoods than her own.

Wolcott and the PHAC encouraged white residents to not flee but to stay and help integrate the neighborhood. Many white residents feared that once black people moved into Park Hill, the neighborhood would fall into disrepair like Five Points. They said black people could live in their neighborhoods if they maintained their homes and lawns. PHAC pressured the city of Denver to keep up city services in Park Hill, including street paving and trash collection.

Anna Jo Haynes, a life-long political activist and African American, joined the Park Hill Action Committee as well. She lived at 26th and Cook, west of Colorado Blvd.

“The PHAC set up dinners where people could spend time talking about race relations,” Haynes says. “They invited speakers who were very involved in what was happening. People could ask questions without being fearful on both sides and wonderful relationships were established.”

Haynes and Wolcott, who each had five children about the same ages, became close friends and champion picketers of segregated institutions. Wolcott picketed taxi companies that refused to hire black people or drive into black neighborhoods. She picketed Denver Dry Goods, a department store that wouldn’t hire black people. She integrated the Cub Scouts.

Martin Luther King Jr. stands before a crowd in 1967 at Montview Presbyterian Church, which was one of several Park Hill churches that banded together to integrate the neighborhood.

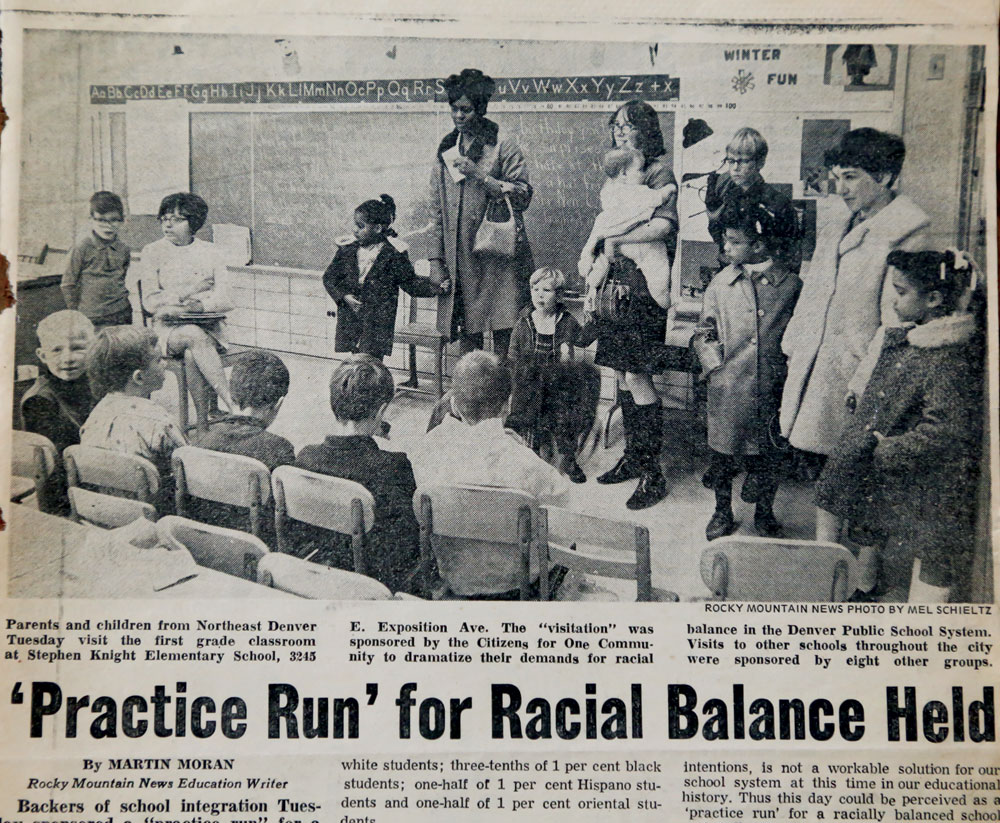

Helen Wolcott (right) and Anna Jo Haynes’ daughters, Lee Ann and Mary, visit Stephen Knight Elementary, 3245 E. Exposition Ave., in 1969. The visit was sponsored by “Citizens for One Community” that supported school integration. At the time, Stephen Knight Elementary, now Knight Center-Early Education, was 98.7 percent white.

The Denver School Board built enough schools in black neighborhoods that the black students wouldn’t need to leave and go to a white school, resulting in segregated schools. Haynes fought for desegregation in DPS.

“Integrated neighborhoods was a bigger issue than just housing,” Haynes says. “It was important to desegregate neighborhoods to desegregate the schools.”

Having all minorities in one area doesn’t solve anything, according to Haynes. It perpetuates lower levels of education, lower standards of achievement among minorities and problems for members of all races and school boards. Haynes’ children were among the first African Americans to volunteer to be bused to predominately white schools for a better education.

Together, Haynes and Wolcott fought for fair housing, once staying at Gov. Love’s office for 48 hours straight until he added it to his agenda. He believed the 1957 Fair Housing Act worked just fine.

Then in 1968, on the heels of Martin Luther King’s assassination, integration efforts in Denver and all over the U.S. gained momentum. Denver’s Noel Resolution (named after Denver’s first black school board member, Rachel Noel) to desegregate schools and the Federal Fair Housing Act were both passed in April 1968.

Helen Wolcott (front) protests with fellow Congress of Racial Equality members outside a home where the owner refused to rent to an African American. Photo by Denver Post/1961

Haynes and Wolcott agree it was a scary but exciting time in Denver. For several years, Wolcott relished the integration in Park Hill. Her block at 23rd and Clermont was half white and half black for several years. Park Hill became a national example of interracial living.

But, fast-forward to today and Park Hill looks very different. Although redlining no longer exists, Park Hill has become less integrated on its own. A 2010 census by the Piton Foundation shows South Park Hill is 84 percent white and not even 1 percent black. North Park Hill is 50 percent white and 39 percent black. Housing prices in Park Hill and all over Denver have skyrocketed. Homeowners who cannot afford to maintain the older homes are taking advantage of increasing home values and moving to the suburbs.

“It’s so frustrating to see what has happened,” Wolcott says. Her block is almost entirely white now.

Haynes, who now lives at 30th and Dexter, which has historically been all African American, is one of four black families left on her block. While the number of young, wealthy families moving in is considered progress in many ways, Haynes fears Denver will become a primarily white city. She calls it “urban removal,” instead of urban renewal. The best example is Five Points, which is now almost all white and the youngest, hippest Denver neighborhood, according to Haynes.

It begs the question: Are the vital interests Park Hill residents fought to protect in the ’60s and ’70s still the interests today? Can integration last? “When leadership isn’t cultivated, when you lose history, you no longer have that same feeling of why it’s important to integrate …” Haynes says. “You have to do what Park Hill originally did, which is have dinners and talk to each other about race. If you have churches, neighborhood organizations and people working together, we might be able to stop the flow of African Americans just leaving in droves.”

I was raised on Dahlia St across from Stedman Elementary School. Our parents bought a home built by my uncle. Wonderful neighborhood to grow up in. Lots of young families with lots of kids. At 33rd and Dahlia was the Dahlia Shopping Center anchored by the largest Kind Soopers in the City. We also had 48 Lane Dahlia Bowl, a Hardware Store, Donut Shop, Cleaners, Soda Fountain and more. At 33rd and Holy there was another shopping center anchored by Safeway and Duckwalls.

The term used at the time was Block Busting. As the African Americans began moving into the area, crime followed them. It wasn’t long until the King Soopers closed down as did the Bowling Alley. We even had the 2nd McDonald’s in Denver built in that shopping Center. Look at it now. All those businesses are gone. The shopping center at 33rd and Holy also closed down too. Crime was even worse there because of a park area built on the east side of Holly St. Gangs helped drive even more people OUT of the area. Homes were being sold for their equity only just so people could get out of Park Hill. The Real Estate agents really did a disservice to the entire area because of the sales tactics.

It wasn’t a good time to be in Park Hill. Even now none of those businesses have moved back. The house my parents bought cost $7,900. I saw on Trulia that it is now valued over $400,000.

Amazing…

The assignation of Dr. King and the inside crime in the grocery stores was the start or the fall. Businesses didn’t want to renew leases or serve people who were born with their tans. Systemic racism, no jobs, summer programs, arts and P.E. in schools started the second phase of destruction. Slacking on city services verses not having to be asked to complete them further south. It’s a part of the plan to create gentrification. Even now the pilgrims have infiltrated divide and conquer by listing North & South Park Hill. SMH

Don’t forget the damn mobile units (trailers) that took away our field day activities. They didn’t want to bus children of color south of Colfax.

Some peoples memories just aren’t the same. I remember one Barrett Elementary school built, as i was enrolled in 1960 as a first grader. There were no junior high or senior high schools built for the Park Hill

community at all. I remember double sessions at Smiley and not asking anyone to integrate any thing or place, but of a decent opportunity to succeed with fair access to education, jobs, healthcare and all other

amenities Denver could muster up. Every one must remember that high schools such as Thomas Jefferson

and JFK were new schools not built for integration, but for white flight. Busing was rampant, first for the grade school children starting about 1964-65. Overcrowding at East High and Manual began about 1968-69.

Yes, MLK JR did meet the colored members of Mountview Prebyterian and the church as integrated but the locale the church related to where blacks lived and worshiped in the Greater Denver area was way off point.

The majority of African American churches of that day were in the Whittier area as they are landmarks today.

Parkhill of the south was not true to the African American existence in north and northeast Parkhill.

Totally different neighborhoods. Five Points crime during the 50’s and 60’s would be negligent

by today’s standards. Upkeep of property by renters was unheard of until the single family homes

were divided into apartments to capitalize on the influx of African Americans leaving Chicago, ST. Louis,

among other cities, headed for the west coast. Denver was at one time merely a rest stop, but upon further

exploration, Denver had some positives and it was that some small number of coloreds were already there.

I am being nice with the reference of the term “colored” not mean spirited at all, but those folk did what they did in order to survive. You must understand that the whites were and still are “the children of the south”. They were not fresh off the boat, they were assimilated for years to be “american” and obedient too the

race, if not for the culture. Not many whites had taken a stand with blacks in Denver for a long time and

as of today all of our apathy has come full circle to gentrification to reverse the integration experiment of

what was only temporary in time to figure out what to do about the kind of blacks that whites do not

like. Now they know what to do. Look around the inner cities and it looks like every where else.

Hello, Living in PARK HILL:1967-1973, privileged to witness lawyer G.Greiner/HOLLAND & HART argue to improve Educ. services/etc. for minority schools in NPK before the US Supreme Court @ WA/DC. WM. O. Douglas as amazing! How can I learn more about today?

Thank you!