Ida Wells (1862-1931) was an educator, civil rights activist and investigative journalist who challenged segregation and advocated for women’s rights and suffrage. Born into slavery, she eventually co-owned a newspaper in Memphis and at great personal risk published her research on lynchings. —Photo courtesy of Cihak and Zima/University of Chicago Photographic Archive

“Reconstruction tells us more about America and who we are than 1776,” says Harold Fields.

The son of a Tulsa plumber, longtime Park Hill resident and former software designer Harold Fields uses a plumbing metaphor to describe the need for reparations for African Americans. “We have pipes that are deep underneath these buildings and underneath our streets. The pipes are decaying, they’re old. They’re leaking, and they are only distributing resources to certain places. You’ve got to be able to dig up those pipes and re-do the system. It’s not a matter of changing the washers on faucets or putting in a new shower head, but changing the system.”

Fields heads the Denver Black Reparations Council (DBRC), established this year to collect and distribute funds for reparations locally, and to show what people can do in the form of “micro-reparations.” Fields emphasizes that reparations is not an event but a process of repairing and healing paired with compensation for hundreds of years of institutionalized injustices that began with enslaving Africans and continued for generations after abolition.

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 essay, “The Case for Reparations,” brought renewed attention to reparations. In a 2019 interview, Coates summarized: “Virtually every institution with some degree of history in America, be it public, be it private, has a history of extracting wealth and resources out of the African-American community.…behind all of that oppression was actually theft. In other words, this is not just mean. This is not just maltreatment. This is the theft of resources out of that community.”

Fields’ father established a successful plumbing company in Tulsa in the years after the Massacre. This early-1940s photo shows a dapper Abraham Fields, (left end of the back row), with his Fields Plumbing Co. employees, several of whom were family members. Harold Fields and Fields Plumbing photos courtesy of Harold Fields

Why Reparations?

The Racial Wealth Gap

Fields grew up in Tulsa, among survivors of the brutal 1921 Tulsa Massacre in which White mobs killed an estimated 300 Black people, destroyed 1,200 homes and decimated “Black Wall Street.” Though one of the most ferocious assaults on Black wealth and Black lives, the Tulsa Massacre is not the only or most recent example of racist assaults on African American wealth accumulation. Throughout US history, overt and covert mechanisms that enjoyed the sanction of law and respectability have conspired to undercut African Americans’ efforts to attain the American dream.

Long after abolition, federal, state, and local governments constrained African Americans’ movement, enfranchisement, and access to housing, education, and economic opportunity. A growing body of scholarship excoriates a host of policies often lauded for growing the American middle class, which deliberately excluded Blacks even as White middle-class wealth grew.

Duke University economist William Darity Jr. and co-author A. Kirsten Mullen offer a variety of means for calculating reparations and determining beneficiaries in From Here To Equality (2020). By all measures, the final figure would be in the trillions of dollars. This calculation would eliminate the racial wealth gap, which the authors see as “the most robust indicator of the cumulative economic effects of white supremacy.”

But I Oppose Government Handouts

“We have a long-term history of massive government subsidies in favor of White people, from the giving of land to preferential treatment to become citizens to preferential treatment for things like being able to organize a union,” says University of Denver law professor and Central Park North resident Tom Romero, Ph.D. Romero points to the Homestead Act as one of many examples wherein the federal government distributed free land to those considered White and largely excluded African Americans. “US policy since its founding…had a whole host of policies and practices that led to massive government subsidies that benefited exclusively White people.”

Racially restrictive covenants such as these from 1940s Denver—pictured here with Prof. Tom Romero—were one of many governmental and nongovernmental mechanisms that restricted African Americans’ access to homeownership. Photo by Joe Mahoney, MSUD Journalism

Romero, who specializes in post-World War II Denver’s unequal housing and educational patterns, enumerates a long list of formal and informal government subsidies to Whites extending into the late twentieth century. “The suburbs wouldn’t have been able to be developed without massive government subsidies tied to the interstate highway system, low-interest federal housing loans, and more.” Discriminatory practices prevented Blacks from moving into communities and White families grew their wealth from homes that appreciated significantly over the years.

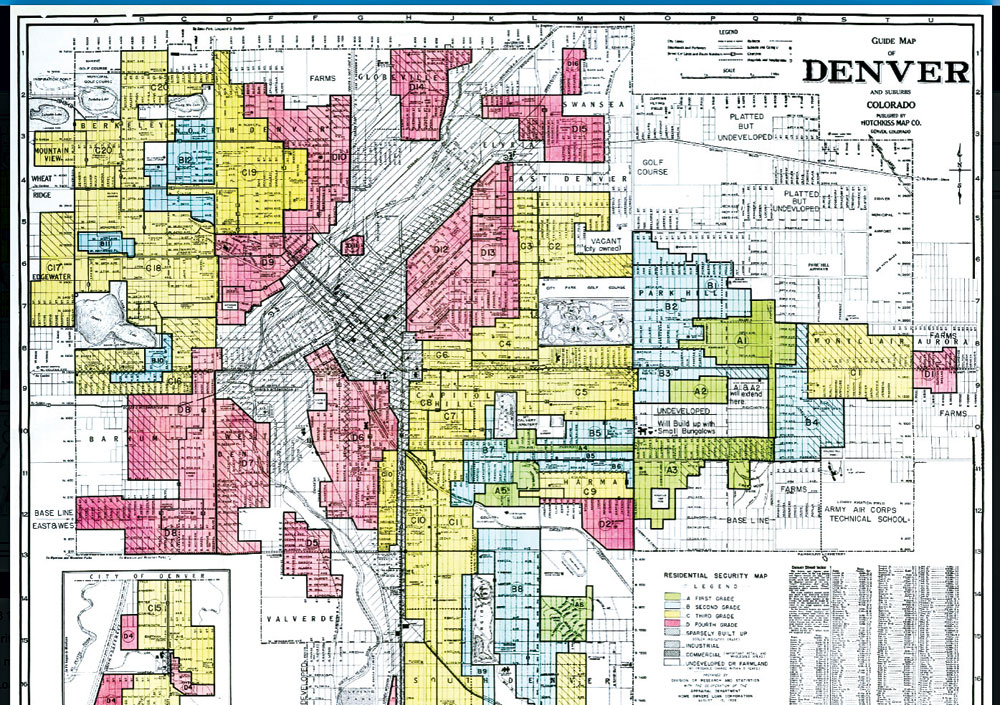

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) made homeownership a possibility for working- and middle-class families but largely excluded non-Whites. This 1938 HOLC map shows the practice of “redlining”: minority neighborhoods (in red) were deemed risky even if middle-class, and a home in red was unlikely to receive a loan. Map courtesy of Denver Public Library.

Redlining, blockbusting, covenants and other practices that promoted segregation and reduced Black wealth accumulation “set us up for decades later, for the same areas to be gentrified. The property values had been lowered, and then younger, richer White people could come in and buy those properties up and raise the taxes and force people out of those neighborhoods,” says Fields.

Segregation By Another Name

By the time Fields grew up in Tulsa, Massacre survivors and others had rebuilt and again created a vibrant Black community. But here and across the nation, the postwar years’ focus on “urban renewal” saw municipalities, urban planners, lenders, and realtors undermine those gains. Urban renewal “recreated segregation and disenfranchised people once again, putting in the highways that would separate neighborhoods and [were] specifically designed to break up and destroy Black neighborhoods.”

Today, zoning often maintains the status quo that emerged out of this continuum of predatory, race-based practices. “It doesn’t matter if you have a black mayor or a gay governor. The plumbing has been devised to distribute things differently to people,” says Fields.

He sees the current calls to maintain single-family zoning in his South Park Hill neighborhood as stemming from the same impulse, “to keep things White. You can’t get the mixture of incomes if you keep single-family zoning. We need to start allowing duplexes and triplexes in South Park Hill.” Fields points out that current zoning laws magnify the accumulation of past disadvantages.

Coming to Terms With Our Past, Looking to the Future

Lotte Lieb Dula believes “everybody’s complicit” in White supremacy because even immigrant ancestors “knew what they were buying into.”

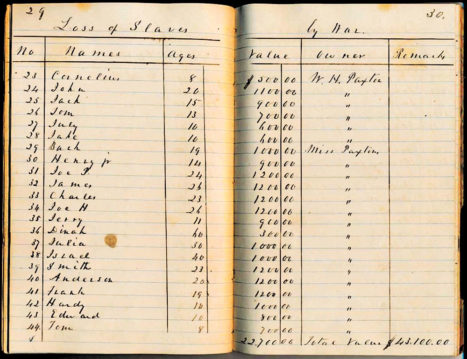

The racial wealth gap is reproduced across generations, often in ways that are invisible or taken for granted by Whites. For Denver’s Lotte Lieb Dula, it became visible a few years ago, when she discovered a nineteenth-century ledger among her mother’s possessions. The financial strategist in her was thrilled to read her great-great-grandfather’s “perfect penmanship” detailing the prices of tools and cotton. Until she came to page 27. There, he began listing the names of the people he owned and their estimated dollar values.

“I was stunned. I realized the stories about my ancestors had been glorified, built up like imaginary monuments to a hallowed but false Southern heritage. Just as Civil War monuments need to be torn down or reinterpreted to match history, the same is true for the narratives families like mine grew up with,” says Dula. Though a self-described “fiscal conservative,” Dula realized “I had to make reparations.” The wealth she had inherited from her maternal grandfather, she now saw, had its roots in slavery. “Generations of my family had gone to law school on money that came from plantation operations,” so she determined to “repatriate” half a million dollars.

Dula’s great-great-grandfather, Elisha Paxton (1795-1867), put his sons through law school with proceeds from his plantations.

“I analyzed the typical vocations my family had pursued over generations—law, civic service, and medicine—and the damage done to African Americans in those fields. Then I worked to create a path toward repair.” She established The William Paxton Cary Scholarship, housed at the United Negro College Fund, for African American students who wish to study law, medicine, or political science.

At the time that Dula’s ancestors were operating plantations in Mississippi and Virginia, Colorado was not yet a state. When President James Buchanan created the Colorado Territory in 1861, the South was seceding. “Our origins and our founding were at the very center of the fight for White supremacy in the US,” says Romero. He reflects on territorial governor and DU founder John Evans’ advocating for “the eradication of indigenous people,” and Colorado’s earliest governing documents.* “We embedded Jim Crow in our legal system from the very beginning. We had laws in the books in our territorial government that required White and Black schools, that prevented marriages between Whites and non-Whites.” White supremacy, Romero says, “is directly tied to the DNA of the state.” After statehood, as elsewhere, federal agencies collaborated with Colorado municipalities, school boards, lenders, businesses and others to maintain residential and educational segregation.

Dula’s soul-searching led her to recognize how little contact she had with African Americans. “Like many people, I didn’t consider myself racist, but if you looked at my life, that wasn’t the case. I avoided race as an issue.” She credits Fields, in part, for her new understanding that “true racial healing comes about when Black and White people work together in relationship. That’s a really critical step. You can’t do this by staying in your White bubble.” She encourages Whites to examine their own histories and “start by making small reparative contributions.”

A page from the ledger Lotte Lieb Dula discovered listing people her ancestors had enslaved.

Reparations is not a partisan issue. “President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which acknowledged and paid reparations to Japanese-Americans who were interned and removed from their homes all along the West Coast,” says Romero. About 82,000 US citizens of Japanese descent received one-time payments and an apology from the federal government for what the Act deemed were actions based in part on “race prejudice.”

Fields is working locally to change hearts, minds, and perceptions. Rather than wait for federal leadership on reparations, the DBRC will work to shift the local picture of reparations. “That’s how movements really gain traction. They have local, grassroots things going on and connect to each other,” he says. The DBRC will support nonprofits as well as “the edgewalkers—those who are trying to bring something new into existence—and give them an opportunity to get their momentum going and begin to grow and germinate.”

*Note: All those interviewed spoke to the need for reparations to the Native Americans whose land we live on. The East Colfax Neighborhood Association maintains a reparations fund in recognition of Denver’s original inhabitants, including the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe tribes. To donate go to https://www.eastcolfaxneighborhood.org/copy-of-our-neighborhood-history.

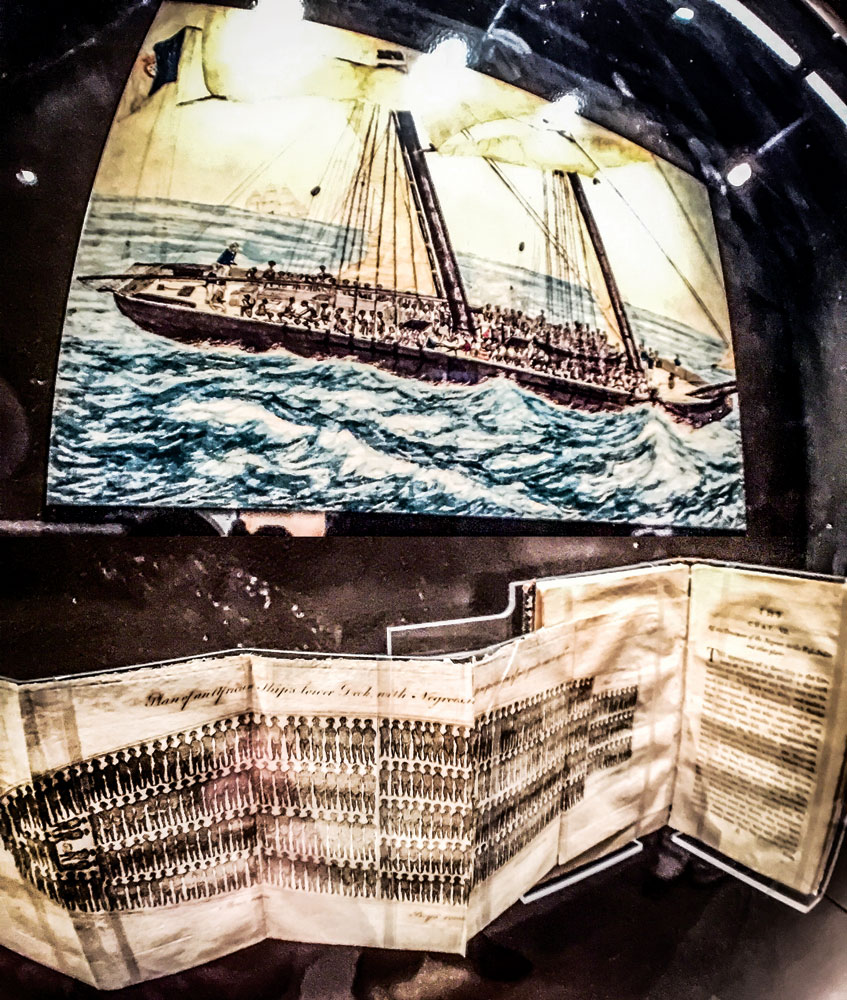

Most visitors to the National Museum of African American History start at the Slave Trade Exhibition, which shows the horrific and inhuman conditions enslaved people experienced.

Above: The Portuguese ship Diligente, seized in 1838 with 600 enslaved people aboard, was engaged in illegal slave trade. Below: Abolitionists in 1788 published this image of how captured people were packed into the British slave ship Brookes.

The Slave Trade Exhibition, three stories below ground level, was designed to feel dark and claustrophobic in acknowledgment of the conditions enslaved people experienced on ships. The sign on the auction block (above) in the Domestic Slave Trade Exhibition includes: “African Americans endured being sold on the block and being devalued to mere laboring hands, feet, backs, and wombs.”

My great great grandfather publish his book in 1925, there’s a lot of true information in his book about slavery and a lot of things he speak on in his book gives a understanding what’s going on now. We need our Reparation and what was taken from us. It’s amazing when it comes to our people is always an issue on everything, which show fear, inferiority and jealousy. They have the nerve to speak on white privileges, there’s no white privileges it’s white curse from robbing, stealing and killing, their lives is chaotic from taking what did not belong to them, they have a lifetime curse from generations to generations. What really gets me, they want to mix with others set of people knowing there curse. There enough for everyone to have a good life however, being inferior, with greed and fear that would be to just. To be honest , there nothing about their lifestyle I want at all they don’t have peace, the mentality is where it is. The time is now, not only will we get our Reparation we will get what was taken from us. I don’t have to have a attitude with them at all, why should I, it’s their problem not mind, I see it from what it really is, I know how far to go knowing what’s really going on with the mentality they really have and it’s very sad.

I am 74-years-old and attribute at least part of my success in life to the fact that I am white and male. Any successful white man my age that doesn’t recognize this about himself is in denial! The solution? I favor reparations on a national level that are financed through taxes. As a middle-class retiree, I would not object to my federal tax bill going up a bit to cover this as long as the tax bills of the rich go WAY UP! As to the details, I favor reparations that are earmarked. A potential recipient should have a choice among something like the following:

– Grants for education (college or technical training)

– Down payments for homes or grants to pay off existing mortgages

– Grants for investment in a new business or expansion of an existing one

I do not favor outright cash grants with no strings attached. It’s not that I don’t specifically trust black recipients to use the money wisely. I wouldn’t trust whites or anyone else to use such money wisely.

I also feel that such a program (or a parallel one) should include Native Americans – the other racial group that has been screwed by white people throughout our history. I have mixed feelings about including Latinos in such a program but certainly would like to see them receive help so they may also prosper.

With regard to Denver, I oppose the current push to radically change zoning to allow for up to five unrelated adults and their family members to live in small homes like mine in southeast Denver. I do not see this as a solution to past housing discrimination. I would welcome more “people of color” into my neighborhood but I support grants to help them purchase homes for their families (including up to three unrelated adults). I also feel that Denver must do more to force developers to build affordable housing – especially affordable housing that minorities can buy rather than rent.

Two responses to this article came in as Letters to the Editor and are posted at https://frontporchne.com/article/letters-to-the-editor-12/

Great article! My eyes are opened…again!