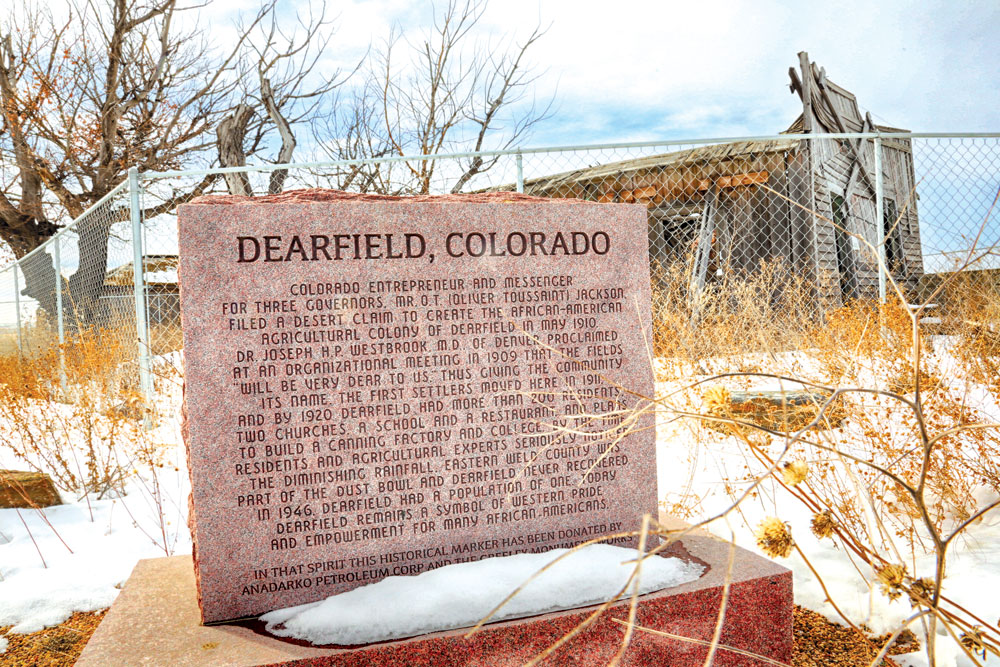

The town of Dearfield, near Wiggins, Colo., was founded in 1910 by Oliver Toussaint Jackson as an African-American agricultural colony and later abandoned in the 1930s during the Dust Bowl.

“Dearfield represents the efforts of African Americans to make better lives for themselves during the era of Jim Crow—to promote creative and innovative ways to aspire to the American dream,” explains Colorado State Historian Bill Convery. In fact, Dearfield was named for the affectionate sentiment its settlers held for the dry plains land that gave them a chance at self-sufficiency.

This current photo shows a monument to the historic town of Dearfield and one of the few remaining structures.

Dearfield Embodies Spirit of Racial Uplift

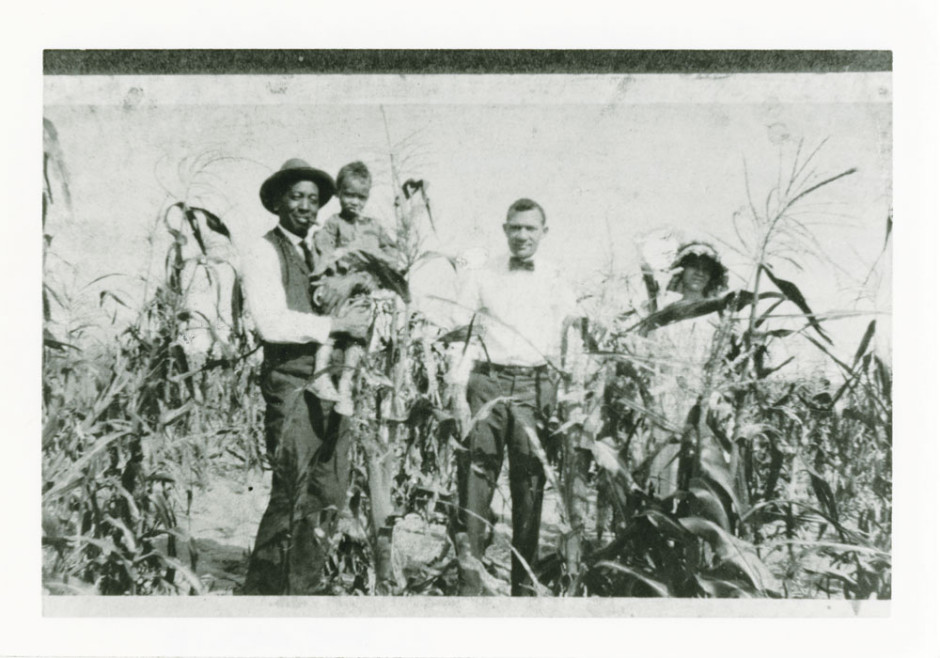

Dearfield’s founder, Oliver Tousaint “O.T.” Jackson, was inspired by the preeminent national advocate for black advancement, Booker T. Washington. Jackson, who migrated to Denver from Cleveland in 1890, was entrepreneurial. According to the Weld County Genealogical Society, Jackson worked as a caterer, a messenger for the governor, he operated a filling station and he worked in real estate. Jackson also established a chapter of Washington’s National Negro Business League (NNBL), an organization designed to “enhance the commercial and economic prosperity of the African American community” (www.blackpast.org).

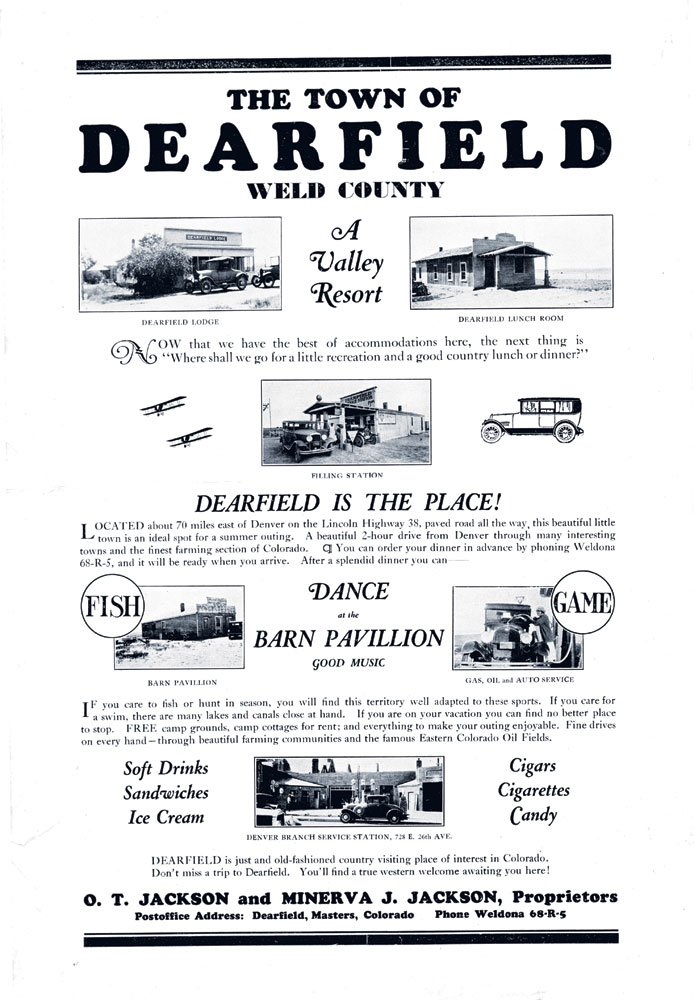

Dearfield was in keeping with the NNBL’s mission. To found the settlement, Jackson acquired 320 acres, nearly 30 miles southeast of Greely, through the 1909 Homestead Act. Jackson then persuaded seven more black families to acquire land. What began with seven homesteaders in 1910 grew to 700 Dearfield residents by 1920. At its peak, Dearfield had over 15,000 acres under cultivation and was valued at $750,000—more than $10 million in today’s dollars.

Town founder O.T. Jackson holds Booker T. Washington, III. His father Booker T. Washington, Jr. at right.

A gathering of buggies and early automobiles in Dearfield.

Twenty-seven black families farmed this land through a process known as “dryland” farming, wherein farmers, in the absence of irrigation, depended upon precipitation to grow such crops as winter wheat, potatoes and sugar beets. For several years, the dryland farming technique yielded enough crops to sustain the community and to sell at the local railroad station.

Erma Downey Ingram, who was raised in Dearfield, described in an oral history interview for the Storytellers Project how her mother and siblings “worked the fields” during the week while her father “walked the tracks” for Union Pacific. Other men in the community, explains Dr. George Junne, professor and chair of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC), worked in places like Denver and Boulder during the week to “raise additional money to purchase farm equipment while the women tended to the families and the fields. The men would return to Dearfield on the weekends to help more.”

This steadfast work ethic illustrates just how “driven the community was to succeed,” suggests Junne, who reasons that there was both a

personal and a communal draw to the idea of Dearfield. Some settlers came because “they loved the idea of black people moving upward,” while others saw in Dearfield the possibility of “land ownership” and personal opportunity in a prospering community.

Photo courtesy of the University of Northern Colorado Archival Services Department.

For Ingram’s family, it was a bit of both. Unlike the exploitative sharecropping system that dominated the South, the all-black community of Dearfield fostered pride in ownership. Ingram recounted her family’s experience in Dearfield with satisfaction: “My folks were working for themselves then. No sharecrop there.”

Nearly 50 years after slavery ended in the U.S., and in an era of white supremacist backlash to black gains made during Reconstruction, the dream of self-sufficiency and prosperity drew blacks to Dearfield. The initial settlers came from cities in Colorado, but once word spread about Dearfield’s success, blacks migrated from places as far away as Arkansas, Tennessee and Georgia.

Booker T. Washington’s support for Dearfield engendered national recognition. This support was gained through Jackson’s NNBL connection and also because Dearfield was much more than a successful plot of agricultural land. The settlement boasted a one-room schoolhouse, a dance pavilion, a filling station, a lunchroom, a cement factory, platted streets, and two churches—one Methodist and one Baptist.

Convery notes, furthermore, that Jackson and Washington had plans to develop an agricultural college there, similar to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Although their plans were eventually foiled by the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Washington’s support of Dearfield suggests that this settlement was significant in its context.

Dearfield Represents Colorado’s Spirit

Dearfield is also significant in terms of Colorado history, embodying as it does both the spirit of the state and the region’s struggles. Dearfield, explains Convery, “represents a dream, and Colorado is full of dreamers. People come here with all kinds of aspirations. For O.T. Jackson and the citizens of Dearfield, that dream of self-sufficiency was enough for them to basically risk everything they had built up in order to achieve that dream.”

While Convery celebrates Dearfield as an inspiration, he also points out “the other part of that story,” which “is a story of how challenging it can be to live in Colorado’s environment. It wasn’t racism that brought Dearfield down,” reminds Convery. “It was the same drought and agricultural depression that wiped out hundreds of thousands of farmers in the Great Plains in the 1920s and 30s. Drought is colorblind. That is the bittersweet story of Colorado, of achieving something special for a very brief period of time and being challenged by the land to sustain that. That’s a very Colorado story.”

There are a handful of Coloradans banding together to preserve the settlement so that Dearfield’s story can be told for generations to come. The Black American West Museum in Denver owns what remains of Dearfield and the museum is continuing to raise funds to “preserve, protect and tell the story of this historical town” (www.blackamericanwestmuseum.org).

Meanwhile, the site—even in its timeworn state—continues to draw both regional and international attention. Junne, who leads walking tours of Dearfield, recalls a busload of German tourists who visited the site a few years back and he mentions that a teacher from Castle Rock brings a group of second-graders there each year. Scholars like Junne will gather on March 7, 2015, for the annual meeting of the Dearfield Association. The meeting will be held at UNC’s University Center from 9:30am–3:30pm. This event is free and open to the public. For more information about the conference, contact Junne directly (george.junne@unco.edu).

0 Comments