Mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton was Denver’s longest serving mayor, serving five terms between 1923 and 1947, with a break from 1931 to 1935.

Activists have recently inundated community meetings urging the removal of the name Stapleton from the neighborhood due to Mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton’s Klan ties during the 1920s. As the community ponders the costs and benefits of a name change, how does Ben Stapleton’s history weigh into the analysis?

Mayor Ben Stapleton, fifth from left, was instrumental in acquiring and constructing Red Rocks Amphitheater for the City of Denver. Though Stapleton thought theaters sinful, he was convinced by Parks and Improvements chief, George Cranmer that it would be a boon to the city.

The Stapleton neighborhood sits on the site of the Stapleton airport, which was named in 1944 for Denver’s longest-serving mayor, who had championed the project and opened it as Denver Municipal Airport in 1929. Stapleton International Airport closed in 1995, but city officials and developer Forest City continued using the name “Stapleton” as a recognizable locator for the neighborhood.

Since 2000, as city leaders worked on the massive redevelopment, there were calls to strike the name Stapleton from the project due to the KKK connection. But “Stapleton” has proved to be enduring, despite repeated assurances from developer Forest City that it is being “phased out.” (See past Front Porch articles from August 2015 and October 2015 for the history of this issue.*)

Understanding the life and times of Ben Stapleton might help shed some light on the issue.

Stapleton and the KKK in 1922–1926

According to Professor Robert Goldberg, who wrote The Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado, Stapleton joined the Klan around 1922, as member number 1128. He was considered an “early joiner,” and thus likely drawn in by Klan recruiting officers (called Kleagles) through Protestant churches or fraternal social organizations like the Masons.

According to Goldberg, Kleagles would arrive in a community and lay low to assess how best to adapt their message. In Denver in 1921, crime was an issue, particularly related to Prohibition violations, so law and order was a key focus, as was anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic sentiment. John Galen Locke, an early leader in the Denver Klan, approached many friends—possibly even Ben Stapleton—to join the “hooded empire.”

A former judge and postmaster, Stapleton likely joined for political reasons. “In the 1920s in the United States or in Colorado, if you had political ambitions or economic ambitions, the Klan would be a good organization to affiliate with,” says Goldberg. “The Klan was not only an organization opposed to crime … but it was an economic machine and a political machine.” Klan membership rolls yield 17,000 names in Denver during the 1920s, and some estimates say that membership reached 20,000 in a city of about 250,000 at the Klan’s height in 1924–1925.

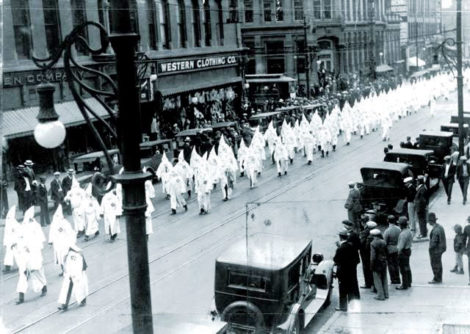

This Klan parade in downtown Denver in May, 1926 appears alarming, but it attracted far fewer than the thousands the waning Colorado KKK had predicted.

Despite the large KKK membership, Colorado was relatively quiet in terms of Klan violence, with no Klan lynchings recorded, although cross-burnings were common. “A cross-burning was a signal that the Klan had arrived, but it could also be used as an act of intimidation,” noted Goldberg. Crosses were burned in the yards of Catholic churches and of men accused of domestic violence. “Kavalcades” of Klan members returned from cross-burnings on Table Mountain, a favorite spot, down through Jewish neighborhoods on West Colfax, jeering and taunting residents as they passed.

Stapleton’s political ambitions became apparent when he ran for mayor in 1923. Born in 1869 in Kentucky and a veteran of the Spanish-American War, Stapleton was a Democrat. In an effort to assuage anti-Klan voters, he stated in May 1923, “True Americanism needs no mask or disguise. Any attempt to stir up racial prejudices or religious intolerance is contrary to our constitution and is therefore un-American.”

But his Klan ties belied his words. This type of strategy was “common practice across the United States,” according to Goldberg, among Klan candidates who wanted to hide their KKK affiliation in order to gain votes.

According to Phil Goodstein, writing in In the Shadow of the Klan: When the KKK Ruled Denver 1920-1926, Stapleton narrowly won the 1923 election against an unpopular incumbent and six other candidates. Although Stapleton appointed some Catholics and Jews to city service positions, he also filled many important roles with Klansmen. He initially refused to appoint a Klan chief of police, however, against the wishes of Locke. “Stapleton wanted to be his own man,” said Goldberg. “He constantly chafed under the leadership of John Galen Locke.”

Just as Klan forces were about to circulate a recall against Stapleton, an anti-Klan group began gathering signatures to recall the new mayor.

To prevent the recall and keep his mayoral seat, Stapleton needed the political power of the Denver Klan. Finally succumbing to KKK pressure, he appointed Klansman William Candlish as the chief of police, accelerating the anti-Klan recall effort against him.

Then, in July 1924, less than a year after his eloquent anti-Klan exhortation, Stapleton reassured KKK leaders, “I have little to say except that I will work with the Klan and for the Klan in the coming election, heart and soul. And if I am re-elected, I shall give the Klan the kind of an administration it wants.” Grand Dragon Locke responded, “You went back on us once. If you ever go back on us again, God help you.” Throughout the recall, Stapleton refused to denounce the Klan by name, despite repeated requests.

Stapleton prevailed in the recall election, thanks in no small part to the Klan forces, and they burned crosses on Table Mountain in celebration of his victory.

Charles Lindbergh (center), Ben Stapleton (third from left) and anti-Klan Governor Billy Adams (second from left), likely at Lowry Field in August, 1927, when Lindbergh visited Denver on his cross-country trip after having crossed the Atlantic.

Stapleton Breaks from the Klan

In 1925, Locke fell out of favor with national KKK headquarters in Atlanta, and questions about his corruption were raised locally. Stapleton, despite his 1924 vows of allegiance, “is constantly seeking to get out from under the hood … waiting for his opportunity,” according to Goldberg.

These setbacks to the Klan gave him “the moment where he thinks he has the opportunity to move.”

After several months of planning and secretly recruiting American Legion members to help, on April 10, 1925, Stapleton ordered the “Good Friday” vice raids across the city in an attempt to break apart a Klan-police force racket that permeated the city. Many Klan police officers were expelled, although the vice raids also targeted many immigrant- and minority-owned establishments.

John Galen Locke rejected Stapleton in June 1925, when the Grand Dragon split from the national KKK organization and formed the Minute Men of America. Also in June 1925, Stapleton officially welcomed delegates to the NAACP convention, and the city “put up street banners to herald the conference,” according to Goodstein. Over 1,500 delegates paraded through downtown Denver.

But Stapleton’s real break with the Klan came when he fired the Klan police chief, Candlish, on July 15, 1925. This was a statement of independence for Stapleton, but it was not accompanied by a public, verbal renouncement. None ever came, according to historians Goldberg and Goodstein.

Instead, the Klan faded from Denver, losing most of its power by 1926, when fewer than 1,000 members remained. Many civic leaders, like Stapleton, who had been involved with the Klan simply moved on, never formally renouncing but no longer doing the bidding of the “invisible empire.”

Accomplishments

After losing the 1931 election, Mayor Stapleton returned to serve three additional terms, from 1935 to 1947. He came to be known as “Ben the Builder” for the many civic improvements that he helped foster. He was known for having organized a strong and effective political machine, inherited from his predecessor, Robert W. Speer.

According to The Denver Post obituary of May 23, 1950, Stapleton made many contributions to the city of Denver. In 1929, he fought to establish an international airport in Denver against opposition that dubbed it “Stapleton’s Folly” and “Coyote Hollow,” after a nickname for the land it would occupy. Some suggested Stapleton merely wanted to make a deal with an old friend who owned the land, but even as the Great Depression took hold, the airport was an immediate success.

Stapleton is also credited with having the foresight to acquire important Western Slope water rights for Denver and gaining access to the Moffat Tunnel to transport that water. Working with George Cranmer, his parks commissioner, Stapleton established many of the mountain parks that Coloradans still enjoy, including Red Rocks. Although Stapleton wanted to keep Red Rocks in its natural state for outdoor enthusiasts, he ceded to the vision of Cranmer, who proposed an outdoor amphitheater.

In the face of doubtful opposition, Stapleton championed and built the City and County Building. Supporters also credited him with “cleaning up” Denver and keeping it clean, with raids against gamblers.

“Accused often of favoring his friends, his intimates explain that the mayor always put Denver’s interests first, and his honorable loyalty to his friends could easily be misunderstood,” noted the Post’s obituary.

Mayor Stapleton breaks ground for the City and County Building on March 26, 1929.

Historian Views

Goldberg is hesitant to support the idea of a name change for the Stapleton community. Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee “committed treason against the United States, violated the Constitution, and fired on federal troops,” and the statues memorializing them, erected long after the Civil War, should never have been put up, he said.

On the other hand, “Stapleton did a variety of positive things for the community,” Goldberg said. “My feeling is that, if you keep Stapleton’s name … it’s so important that you have a corrective with the name … which indicates there is a flaw here. This is not somebody to be honored, but somebody to be reflective about and learn from.”

State historian Patty Limerick, who was not available to comment for this article, had expressed a similar view in comments made on Colorado Public Radio last month, when she said, “Benjamin Stapleton is one high-powered cautionary tale” that the community can learn from. “How do we draw upon his experience to make our choices wiser?” she asked.

If you erase the name, said Goldberg, “You lose the chance of learning something, you lose an educational moment … there is a dark side also to be known.”

“It’s not important to forget him. It’s important to remember him, in all of his facets,” said Goldberg. “As a member of a minority, I understand that anxiety” that people of color experience when the KKK is evoked,” he continued, “but at the same time, erasing it does not improve it.”

https://frontporchne.com/article/stapletons-name-changed/

Sounds like a pretty cool guy, very tolerant how he decided to build red rocks even though it was sinful.

Also very unbiased sources, Goldstein and Goldberg, I’m sure they truly understood Denver at that time.

I respectfully disagree. I think the name should change but an explanation be put in Central Park as to why so the cautionary tale is remembered and learned from as you suggested. I think your conclusion about the story is correct but I don’t think keeping the name is the way to send the message of learning. We should be the example in Colorado of how the rest of the country should respond. Do both. Show respect to those who are reminded of the tirany of white privilege and racism while also putting the dark history out there for people to learn from. We still have a ways to go in building an equitable society but it has to begin with correcting our view of people who collaborated with violent bullies. It’s not ok period. Let’s set a precedent. Let’s be independent and lead the country.