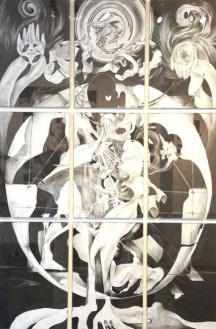

Park Hill residents (left to right) Alison, Tayler, Jordan and Phil Canjar stand in front of Jordan’s art at In Our Own Voice, an anti-stigma event when speakers share realities of living with a mental illness. Jordan presented his art that depicts his time in psychosis.

For hours, Park Hill resident Alison Canjar desperately left voicemail after voicemail trying to find someone who could help her 19-year-old son, Jordan. At this point Jordan was in psychosis and needed immediate attention. Not knowing what else to do, Alison and her husband, Phil, had taken him to the emergency room, but he was discharged because the hospital wasn’t equipped to treat him. So Alison returned home, looked up the psychiatrists covered under their insurance, and began calling each one. The only doctor who called her back could see Jordan in a week, a long time for him to be out of touch with reality.

“Things can get pretty bad before they get better when it comes to a brain illness,” Alison says.

Certain parts of Jordan no longer seemed present—he lacked motivation and became disinterested in others. Those characteristics were replaced with new behavior—inappropriate reactions, unpredictable agitation, negativity and refusal to agree to requests. His symptoms would come and go. Initially Alison and Phil mistook the symptoms for normal adolescent behavior, but over time they became more regular and severe. At the point they brought him to the ER he was having delusions and hallucinations.

Soon after visiting the psychiatrist, Jordan was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

While mental illnesses can be debilitating, they are treatable. With the right support and medication, Jordan, now 25, lives a productive life. He works, has a healthy relationship with his family, and finds meaning in art. Without treatment, however, symptoms reappear.

“To allow sick people to linger without care is unconscionable,” Alison says. “We would never allow people to linger and decline with illnesses that affect other organs of the body.”

Comedian and actor Robin Williams’ suicide has brought attention to mental health care in the U.S. His unexpected death showed depression and mental illnesses can affect anyone, even those who appear to have everything.

According to the National Institute on Mental Health, 57.7 million adults live with a mental illness in the U.S. That doesn’t include the population of people who are misdiagnosed or untreated.

The individual panels put together make “a reference to Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch Vitruvian Man,” Jordan says.

The consequences of untreated mental illness for an individual and society are staggering, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Unnecessary disability, unemployment, substance abuse, homelessness, inappropriate incarceration, suicide and wasted lives are some of the main consequences. The economic cost of untreated mental illness is more than $100 billion each year in the U.S.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made many changes that could potentially provide support and treatment to improve the lives of people living with mental illnesses.

Beginning in January, insurance plans have been required to have 10 “Essential Health Benefits,” including substance abuse disorder and mental health services like depression screenings or psychotherapy. States cannot apply a cap on the coverage for the essential benefits. Insurers also cannot deny anyone coverage or charge more for pre-existing conditions, including mental health conditions.

The services must also follow parity, or be on fair and equal terms, with other medical care. The Parity Law was created in 2008 to stop insurers from discriminating against those with mental illnesses. The rule has been brought back through the ACA.

While these changes, in theory, should guarantee a person living with a mental illness should not get worse, receiving treatment continues to be a challenge—parity is confusing, benefits vary greatly from plan to plan, and treatment often isn’t available, according to Scott Glaser, executive director of NAMI Colorado, where Alison has now volunteered for three years and Phil one year.

In Colorado, the network of doctors cannot provide for all the people seeking treatment due to the Medicaid expansion, which has added 178,000 people to the system, according to the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing. “The system is so overloaded it’s not funny,” Alison says. She figured the scramble of phone calls would end after Jordan’s diagnosis, but at times he has had to wait up to three months to see a psychiatrist.

“The Canjars’ situation is pretty typical,” Glaser says.

Colorado fluctuates between 48th and 49th in the U.S. in terms of psychiatric hospital beds per capita, according to Glaser. NAMI is part of a coalition working to start a 24-hour hotline and drop-in respite and care center for people who need immediate treatment.

Although areas of the mental health system need improvement, Glaser says the stigma of mental illness is getting better. NAMI hosts anti-stigma events called In Our Own Voice when speakers share realities of living with a mental illness. Jordan recently presented his art that depicts his time in psychosis.

Under the ACA, Jordan can stay on the family plan for one more year, until he turns 26. The Canjars are hopeful access to treatment will improve. “Whether it will or not depends on our understanding and having compassion for those who suffer from illnesses that affect their brains and taking steps to improve the level and quality of care they receive,” Alison says.

0 Comments