History Colorado Executive Director Steve Turner, next to Alexander Phimister Proctor’s 1914 statue, Buckaroo, took the reins of the History Colorado Center last year and is bringing back a focus on Colorado history.

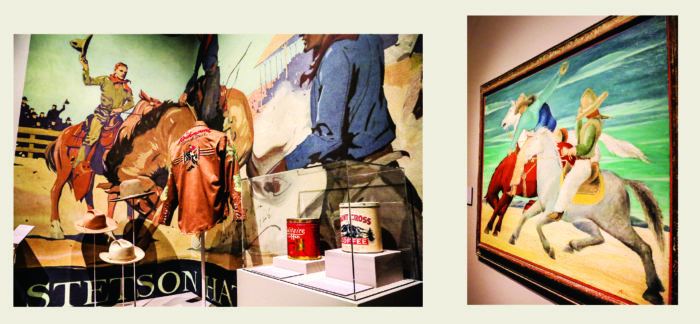

The March opening of Backstory: Western American Art in Context at History Colorado Center stamps the imprimatur of a new era on the institution, but one that returns the museum to its heritage, rooted in local and material culture.

Back Story: Western American Art in Context

When Meriwether Lewis looked through his telescope (above), he might have seen a view something like that depicted in Alfred Jacob Miller’s painting (below) of Lake Fremont and the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming.

Backstory pairs artifacts from the History Colorado Center’s considerable archives with Western Art from the Denver Art Museum’s collection to tell the story of how the West evolved from its ancient roots to modern times. In a testament to the collaborative attitude of the city’s cultural institutions, the Denver Public Library and the Denver Museum of Nature & Science also contributed to the exhibit, which is sponsored by the Sturm Family Foundation.

Steve Turner, the executive director of History Colorado described how a dinner party conversation with DMNS’s president, George Sparks, led to the inclusion of a particularly important artifact in the exhibit. “We were talking about the exhibit and he just said to me, ‘We have Lewis and Clark’s telescope. You should put this in the exhibit.’” And lo and behold, that iconic item is on display as an introduction to the European exploration of the American West.

The exhibit is already popular, with Colorado historian and UC Denver professor Dr. Tom Noel counted among its fans. “It is a great example of partnering with other organizations like the Denver Art Museum,” said Noel, “To my knowledge, it’s an original idea, where they combine art from the museum and artifacts from History Colorado and do an interpretation of it.”

The Backstory of History Colorado Center

C. Paul Jennewein’s 1932 statue Indian and Eagle presents an artistic view of its subject.

Backstory represents an important turning point in the evolution of the flagship museum of Colorado’s State Historical Society, a path that has seen more than a few ruts in its road in recent years. [The State Historical Society of Colorado was founded in 1879 and maintains museums across the state. Officially named History Colorado, the society is a state agency, its board and executive director appointed by the governor, and its budget likewise tied to the state.]

For many years, the Colorado History Museum occupied a building not far from the Capitol, where it displayed its collection of historical artifacts. But much changed in 2012, when the re-named History Colorado Center opened its doors in a flashy new, architect-designed building and began to change the types of exhibits it offered in a bid to broaden its appeal and increase attendance.

David Halaas, former chief historian of the Colorado Historical Society, has watched the story unfold. “The purpose of a museum is to show real stuff, a place where things of the past, artifacts, are preserved and interpreted,” he says. But after the opening of the new building, the “inexperienced” new administration “stopped showing stuff. They made it basically into a kids’ museum. They were trying to attract families, but they stopped putting out stuff,” said Halaas.

The artifacts from History Colorado’s collection, including a photograph of a Ute encampment in 1874, an Arapaho cradleboard and a Sioux dress from the late 19th Century show the reality of the time.

Another focus that the museum took after its move was bringing in expensive exhibitions from outside vendors. Although exhibits like Race, 1968, and Toys were successful in terms of audience reception and increasing attendance, “they cost more to rent than they brought in revenue,” said Turner. “Everybody wants the next King Tut, and the problem is those kinds of exhibits are very few and far between.” Limited to second-tier exhibits, the museum faltered in its new home.

Part of the West’s Hispanic heritage, bear roping was a popular sport and way to manage predators, as depicted in James Walker’s dramatic 1877 painting, Cowboys Roping a Bear.

During this period, the museum also came under fire for its exhibit on the Sand Creek Massacre, in which more than 160 American Indians—most women and children—were slaughtered by Colorado Territory militia. The museum put up the exhibit “without consulting with the tribes. It was a travesty,” said Halaas. “Even though they were told by the tribes and by historians that what they had going was awful and shouldn’t even open, they went ahead with it.” After a year of controversy, the exhibit closed in August 2013.

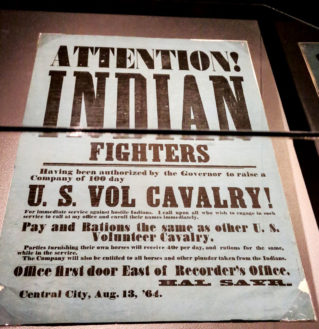

Former Civil War soldiers were recruited to the West as “Indian fighters,” for the Colorado Cavalry, with promises of plunder and horses announced on recruiting posters.

Halaas believes the failure of the Sand Creek Massacre exhibit was the catalyst that spurred Gov. Hickenlooper to re-examine the entire institution. In addition, the museum, which receives no money from the state general fund and depends on gaming revenue, was struggling with significant budget shortfalls. The governor whittled down the unwieldy board from 30-plus to nine members, and in turn the board whittled down the staff. Cuts included its former director, Ed Nichols, the state historian, several other top executives, and more than 22 percent of its employees.

The New Era

Left standing after the shedding was Steve Turner, an architect who had served as the director of the State Historical Fund. Appointed as interim co-director in the wake of the layoffs, Turner became the new executive director in June 2016, tasked with rebalancing the institution’s finances and exhibitions.

Turner is well aware of the challenges of trying to attract a wider, younger audience but still serve as a historical museum. He wants it to continue to be “very family-focused, family-friendly, but we want to expand our audience also and have something for folks that might be coming for a little bit deeper content or more serious exhibits. We want to have something for everyone.” He also recognizes the value of the museum’s extensive collection, which does not come with the hefty price tag of rented exhibits.

The artifacts – including uniforms and Civil War drums – represent the people who came West, such as Lorenzo Taylor (pictured).

Turner and his staff have instituted a five-year plan for exhibitions, and as they ponder what to include, they consider these criteria: Is there a Colorado connection? Is this topic relatively well-represented in our collection? Are there subject matter experts available? Do we think there’s an audience for this?

In addition to Backstory, which fits those criteria, the museum has a number of interesting exhibits in the future lineup, including a history of Colorado told through 100 objects; an exhibit on Caribou Ranch, the iconic recording studio; “Cash Crop” on marijuana; a history of beer in Colorado; and one on “Horse Power,” which should appeal to ranchers and horse-obsessed little girls alike. They also plan to work closely with tribal officials on a new Sand Creek exhibit, one that is “truthful, balanced, and that reflects their perspective too, because it is their story,” said

Frederic Remington’s statue, Bronco Buster (Wooly Chaps).

Turner.

Reception

Fortunately, the old guard is in approval of the new era, which brings back some of what makes a historical museum so unique and important. “There’s been a big change in management and the new management is much more interested in showing the treasures the museum has rather than buying canned exhibits from other places,” said Noel, who is glad to see a renewed focus on real artifacts and not facsimiles.

Halaas agreed. “The present administration is working very hard to be a historical museum where you have artifacts. It’s now going in the right direction. I’m very impressed with Steve Turner … he’s very sensitive to what a museum should be.”

In the 20th Century, color photography began to gain currency. Artifacts of a photographer and a 1917 photograph by Coloradoan Fred Payne Chatworthy showing Theodore Wores painting in Taos demonstrate this development.

In Taos painter E. Martin Hennings’ 1925 painting, Rabbit Hunt, the overly romanticized view of American Indians has been replaced by a more realistic depiction, including the blend of modern and traditional clothing worn by the male figures.

A collection of actual cowboy equipment from John M. Kuykendall, a Confederate Civil War veteran and cattle rancher who settled in Wyoming.

0 Comments