Nicole Shore holds her 20-month-old identical twins Ciela, left, and Mila, right, at a park near their Lowry home. At back, Shore’s husband, Ari, pushes their 5-year-old daughter, Eyla, on the swing. Front Porch photo by Laura Mahony.

Children’s Hospital Colorado is pioneering treatment for a not-so-rare fetal disease called twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS).

Identical twins usually share the same placenta, which has an extensive vascular network to provide blood to the fetuses. When functioning normally, the placenta delivers blood equally to both twins. Due to abnormal placental vascular development, twins with TTTS do not get equal blood supply. One twin, “the donor,” is constantly losing blood supply to the other twin. The decreased blood volume results in poor growth and decreased amniotic fluid. “The recipient” twin gets an excess of blood volume resulting in overload of the heart’s ability to pump the blood supply and overproduction of amniotic fluid. The disease affects 10 percent of identical twins and generally develops when the mom is about 20 weeks pregnant, but can occur at any point.

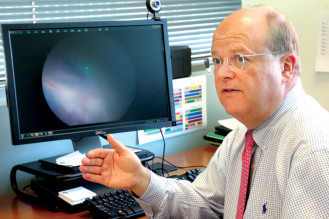

In his office at the Colorado Fetal Care Center at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Timothy Crombleholme, MD and surgeon-in-chief, shows on his computer a microscopic image taken of the placental surface. Crombleholme and his fetal care team use these images to map out every single vessel and mark where they intersect. For an unknown reason, these connections can cause an imbalanced blood supply between identical twins, known as twin-twin transfusion syndrome.

Historically, TTTS has flown beneath the radar, often leading to missed or delayed diagnosis. If untreated, the problems resulting from unbalanced blood supply may be fatal for one or both babies in the majority of cases. In addition to the fetal growth and fluid concerns, the donor twin may have severe anemia at birth. The recipient twin may have polycythemia, an excess of red blood cells, which can result in strokes and other health problems.

But a turning point took place about 20 years ago. Timothy Crombleholme, MD, director of the Colorado Fetal Care Center and surgeon-in-chief at Children’s, started doing a laser surgery that increased the survival rate to 95 percent for at least one baby and 80 percent for both babies. The surgery uses a laser to remove some of the abnormal vascular connections between the circulations of the two twins to help the blood supply to rebalance. “We have the best survival stats of anywhere in the world, and it’s not because we are so wonderful, but because we recognize the things that improve survival,” Crombleholme says.

Crombleholme is shown in the operating room during surgery to treat twin-twin transfusion. He fires a laser at each of the vascular connections to re-flow the blood evenly to both twins. Photo by Scott Dressel-Martin.

When Lowry residents Nicole and Ari Shore sat down with Crombleholme—only 10 days after the Colorado Fetal Care Center opened in 2012—they went over the slew of tests from the day that confirmed she had developed TTTS, somewhere between 20 and 22 weeks of gestation. At that point, the donor twin, Ciela, had no visible bladder on ultrasound and was pressed tightly to the placenta. Those findings showed that she had severe loss of blood volume. The recipient twin, Mila, had way too much fluid resulting in ultrasound findings of heart failure and polyhydramnios.

In addition to TTTS, Nicole had placental insufficiency, in which the placenta does not grow adequately to provide the necessary oxygen and nutrition to the fetus. As a result, the twins were in a precarious position. Nicole and Ari didn’t even need to discuss whether to go forward with the surgery; they looked at each other and knew they had to do it. Because there are risks associated with the laser surgery like pre-term labor or hemorrhage, a small minority of parents opt for an amnioreduction, which drains amniotic fluid from the sac of the recipient twin but isn’t able to transfer it to the donor twin. “We had very few options: do the surgery, have an amnioreduction, which has no guarantees, or do nothing at all. Of course we wanted the surgery,” Ari says. They went home for the night, attempted to sleep, and returned in the morning for the surgery.

Before starting the laser surgery, Crombleholme and his fetal care team use a microscopic lens inserted into the uterus to visualize and project an image of the placenta on a screen and map out every single vessel, which can be in the hundreds. They mark the points where the vessels intersect, which typically ranges from three to 60 points. These are the connections that result in the imbalanced blood supply of TTTS.

Then, Crombleholme fires a laser at each of the vascular connections individually to disentangle the placental blood supplies of the two twins. When he first started doing this surgery 20 years ago, he took about 10 minutes to laser all of the points, but through the years he discovered the less time lasering, the higher the survival rate of both twins. If it takes more than 10 minutes, the donor survival is 78 percent. A 5–10-minute procedure results in 85 percent survival. Less than 5 minutes results in 92 percent survival. He now averages 2.5 minutes with the laser. After the first round with the laser, he goes back three times to check that all connections have been properly closed. If a single connection is not closed, the surgery is pointless and TTTS persists.

“In the waiting room, I was looking at the clock nonstop because I knew it matters how long he’s in there with the laser,” Ari says.

The surgery to evenly redistribute blood for Mila and Ciela was a success. Afterward, Nicole was on bed rest for the remainder of her pregnancy and delivered the twins at 32 weeks. The twins are now 20 months old and happy, healthy toddlers with no evidence there were any complications during pregnancy.

There have now been 5,000 to 6,000 fetoscopic laser surgeries completed worldwide for TTTS. Crombleholme is currently the only one at Children’s who is qualified to do the surgery and sees about 150 cases or more a year from all over the U.S. and even abroad. He is seeing an increase in the number of cases as more obstetricians know to look for the signs of TTTS in a twin pregnancy.

Nicole joined a TTTS support group online where at least once a day a mother in the U.S. posts about losing one or both of her babies to TTTS. “The outcomes now are better than they’ve ever been. We still have a lot of work to do, but we’re doing better with this diagnosis than ever before,” Crombleholme says.

Thank you for sharing this amazing story. For those that may be interested, there is a 5K run/walk in November at Washington Park (The Great Candy Run) that benefits the Fetal Health Foundation. The Foundation supports families, funds research and raises awareness for TTTS and other fetal syndromes. The event is presented by the Colorado Institute for Maternal and Fetal Health, in association with Children’s Hospital Colorado, University of Colorado Hospital and University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Thank you for sharing, Michelle. Please feel free to also add this event to our events calendar at: https://frontporchne.com/submit-event/