This statue of Clara Brown is on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

“People like Clara Brown are rare. She saw her role in the world not as ‘I’ or ‘me’ against ‘them,’ but as ‘us’ and ‘we,’” says Dr. George Junne, professor of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado. “It was the way that she lived her life that garnered her the amount of respect that she received.”

Ex-slave-turned-pioneer Clara Brown is one of Colorado’s favorite heroes. Born sometime in 1800 (slaves’ birth records were sketchy) and freed from slavery at age 56, Brown made her way to Colorado’s Gold Rush in Central City. She started a laundry business for the miners, as well as using her skills as a midwife, cook and nurse. She also used her earnings to help miners get started. “In Central City she was a picture of kindness—so much so that the miners repaid her services with grubstakes [shares in their profits],” said Suzanne Ramsey, librarian and technology teacher at Bill Roberts School in Stapleton. Ramsey (formerly Suzanne Frachetti) wrote Clara Brown: African American Pioneer in 2011 for third- and fourth-graders.

When the miners made money, so did Clara—a lot of money. “A great deal is made of the fortune she acquired through hard work and wise investment,” said former Gilpin County Manager Roger Baker. “But the ways in which she used that fortune went well beyond anything I had ever heard—or I think beyond what anyone today really understood.” 1

Dr. George Junne, professor of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado, is pictured doing research at Dearfield, an abandoned African-American townsite in Colorado.

Photo by Woody Myers for the UNC Magazine

Filmmaker Patricia McInroy produced Clara, Angel of the Rockies, a documentary that premiered on PBS in 2017. “Once I heard Clara Brown’s story, I couldn’t not do the film,” McInroy said.

Brown shared all she had with people in need. She became known as an “angel” because she helped people of all races who were in need of a place to stay, a home-cooked meal, or a kind word. In 1890, the Denver Republican wrote, “She was always the first to nurse a sick miner or the wife of one, and her deeds of charity were numerous.” 2

Her generosity was even more remarkable given her background. Born into slavery in Spotsylvania County, Va., Clara and her mother were sold to a farmer named Ambrose Smith when she was about 3 years old. Smith’s family moved to Russellville, Ky., where Clara and her mother worked as field hands.

“She was converted at age 8. It was a great awakening that influenced her life from that point on,” said Gwen Scott, a former reenactor who portrayed Clara Brown. 3

“She never lost that faith,” Junne said. “It was the basis for what she did.”

At age 18 she married another slave named Richard and had four children, including twins Eliza Jane and Paulina Ann. Paulina Ann drowned when she was 8. In 1835, Ambrose Smith died and his family had to sell the farm and all the slaves. Slave families were often sold separately to bring the most profit. “It was a typical thing for families to do when there were bills they couldn’t pay,” said Tamara Rhone, instructor of ethnic studies at East High School.3

Clara’s family was broken up and everyone was sold to different owners, her husband and son to owners in the Deep South. “It was like being sold down the river, which definitely shortens your lifespan,” said Rhone.

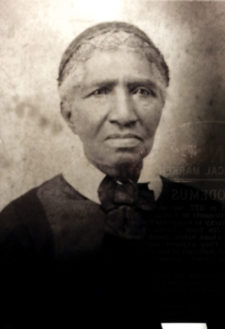

This Clara Brown portrait was photographed at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“It’s inspiring to me that through her hardships, she never became embittered or angry,” said Ramsey.

Clara was bought by a Kentucky hatter named George Brown and spent the next 20 years with his family as a house slave and surrogate mother to the family’s three daughters. She took “Brown” as her last name, as many slaves took the name of their master. While she was with them, Clara became known as “Aunt Clara.”

“The term ‘aunt’ can be taken two ways,” Junne said. “At this time, many white people wouldn’t call a black person Miss, Mrs. or Mr.; they used ‘aunt’ or ‘uncle’ to move away from that. It depends on who’s doing it and for what reason. I prefer to call her Mrs. Brown.”3

In 1856, George Brown died and Clara was granted her freedom papers. Because Kentucky law said that a slave had to leave the state within a year or else be put back into slavery, George Brown’s daughters found Clara a job in St. Louis.

There Clara heard that her eldest daughter had died of a fever, and that her husband and son were lost. She was determined to find her daughter Eliza Jane and, thinking she might have traveled west, Clara traveled to Denver with a wagon train in 1859. It was against the law for an African-American to buy a ride on a wagon train, so the trail boss let her cook and do laundry for the 26 men to pay her way. She walked alongside and slept under a wagon at night.2

When she arrived in Denver in 1859, it was just a few tents and cabins along the river. The U.S. Census listed only 23 black people living in Denver. By 1860, the Gold Rush had moved to the mountains. Clara traveled to Central City on a stagecoach, posing as a young man’s servant because non-white people could not buy a ticket. 4

“She was a true pioneer because she traveled into the unknown with only her abilities and her sense of self-worth,” said Ramsey.

Her success in Central City in the laundry business, and as a mining investor, allowed her to acquire real estate there, as well as in Denver and other mountain towns. “She had $10,000 in her saving account, which is like $150,000 today,” said Rhone.3

This stained glass window of Clara Brown is in the old Supreme Court Chamber at the Colorado State Capitol Building.

“She believed in giving back so she didn’t keep her money,” said Junne. “She took Christianity to mean to be Christ-like; she took it to heart. When the Civil War ended in 1865, blacks were moving out of the South because Ku Klux Klan-type groups were forming. Brown had gone back to Kentucky to find Eliza Jane but instead found ex-slaves in need of help. She paid for a wagon train to take a group of ex-slaves—as many as several dozen—back to Colorado, and found them jobs in the mines.”3

By 1880, Brown’s health was bad and she had lost many of her properties to fires and floods. She moved to Denver for the lower altitude. “She continued to look for her daughter,” said Rhone. “Thinking that Eliza Jane was still out there—that was her resilience. She never gave up that hope.”3

“She asked every wagon train of black people what they knew of her daughter,” said Junne. “Finally a letter arrived with a clue that Eliza Jane was in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Clara’s in her 80s now, but she gets on a train.”3

It was raining in Council Bluffs and according to witnesses, when Clara and Eliza Jane met they were hugging and they fell in the mud. There they sat, unwilling to let go. 5

Eliza Jane had four children, so Clara found grandchildren she didn’t know about. When Clara died on Oct. 26, 1885, she was surrounded by her family. Her funeral was attended by Denver’s elite, including Denver Mayor John Routt and Colorado Gov. Benjamin Eaton.3

“It shows how highly thought of she was, not only by black people but by white people,” said Junne.3

Watch the documentary at www.pbs.org/to-the-contrary/watch/6806/film-festival-winner-for-us-history_-clara_angel-of-the-rockies.

——————————————————

- Calhoun, Patricia. “Gilpin County Manager

Roger Baker on Why Colorado Remembers

Clara Brown.” Westword, Jan. 4, 2017.

- Frachetti, Suzanne. Clara Brown: African

American Pioneer. Palmer Lake, Colorado: Filter

Press, LLC, 2011.

- Clara Angel of the Rockies. Produced by Patricia

McInroy, 25 minutes, 2017.

- Danneberg, Julie. Amidst the Gold Dust: Women

Who Forged the West. Golden, Colorado:

Fulcrum Publishing, 2001.

- Lowery, Linda. One More Valley, One More Hill:

The Story of Aunt Clara Brown. New York:

Random House, 2002.

What a great woman, to bad the world went to hell after people like this left it. RLM