“She’s a ticking time bomb.” The desperation in the mother’s voice is palpable as she talks about how her middle school student spent many months self-harming and has even threatened to kill herself. Her daughter has gone through numerous therapists, multiple visits to the emergency room, a six-day stint at Children’s Hospital, and several outpatient treatment facilities. Nothing has worked and her mother isn’t sure where to turn next. “These facilities have set up an assembly-line system. They don’t examine the underlying behaviors and so they release kids from treatment without really treating them.”

“She’s a ticking time bomb.” The desperation in the mother’s voice is palpable as she talks about how her middle school student spent many months self-harming and has even threatened to kill herself. Her daughter has gone through numerous therapists, multiple visits to the emergency room, a six-day stint at Children’s Hospital, and several outpatient treatment facilities. Nothing has worked and her mother isn’t sure where to turn next. “These facilities have set up an assembly-line system. They don’t examine the underlying behaviors and so they release kids from treatment without really treating them.”

To protect the child’s identity, Front Porch is not publishing the mother’s name, but in a series of interviews, the Central Park mom talked about how the mental health system in Colorado is failing her child. She says most facilities can’t take new patients and those that do “treat ‘em and street ‘em. They want to get kids in and out as quickly as possible, so they triage out anyone they don’t want to deal with,” she says.

She is not alone. Jim Wiegand is a Jefferson County father of seven; four were adopted from the foster care system. One child experienced a severe mental health breakdown when she entered middle school and “the trauma dam burst. Everything came uncorked,” says Wiegand. The young girl suffered PTSD and threatened suicide. For two years, she went through multiple treatment programs in Colorado until officials told Wiegand they couldn’t serve her anymore. In desperation, Wiegand sent his daughter to a residential treatment center in Georgia, where she stayed for 15 months. She is now back home and doing well, but Wiegand is frustrated that Colorado seems to lack essential services to help young people in severe crisis. “Families should not have to fight this hard to get the care their kids need to heal and thrive,” says Wiegand.

She is not alone. Jim Wiegand is a Jefferson County father of seven; four were adopted from the foster care system. One child experienced a severe mental health breakdown when she entered middle school and “the trauma dam burst. Everything came uncorked,” says Wiegand. The young girl suffered PTSD and threatened suicide. For two years, she went through multiple treatment programs in Colorado until officials told Wiegand they couldn’t serve her anymore. In desperation, Wiegand sent his daughter to a residential treatment center in Georgia, where she stayed for 15 months. She is now back home and doing well, but Wiegand is frustrated that Colorado seems to lack essential services to help young people in severe crisis. “Families should not have to fight this hard to get the care their kids need to heal and thrive,” says Wiegand.

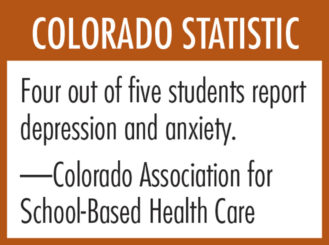

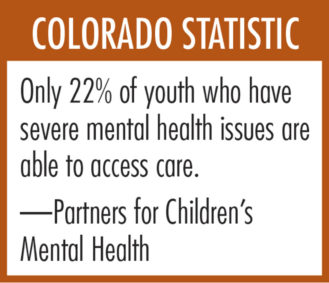

The statistics about the youth mental health crisis are sobering. Only 22% of Colorado children and youth who have severe mental health issues are able to access care. Colorado ranks 42nd in the nation for access to mental health services for children and youth. And, most alarmingly, suicide is the number one cause of death among youth ages 10-19.

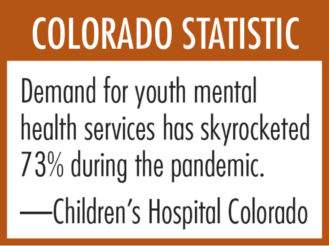

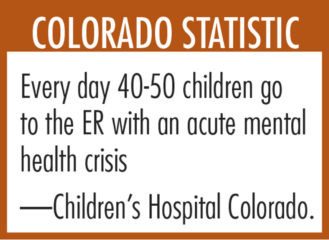

David Brumbaugh, chief medical officer at Children’s Hospital of Colorado says the need for youth mental health services has skyrocketed by 73% since the pandemic began. “From the start of the year to mid-October, there have been more than 5,000 emergency room behavioral health visits for children in crisis,” says Brumbaugh. “On any given day, there are 40-50 kids suffering an acute mental health crisis presenting to our emergency departments.”

David Brumbaugh, chief medical officer at Children’s Hospital of Colorado says the need for youth mental health services has skyrocketed by 73% since the pandemic began. “From the start of the year to mid-October, there have been more than 5,000 emergency room behavioral health visits for children in crisis,” says Brumbaugh. “On any given day, there are 40-50 kids suffering an acute mental health crisis presenting to our emergency departments.”

Two weeks ago, Brumbaugh and a consortium of health and school officials sent an urgent plea to elected officials: it’s time to make significant investments in youth mental health or the crisis will continue to spiral out of control. They say more mental healthcare workers need to be trained and hired, in-patient facilities need to be expanded, and community and school-based clinics need to be more broadly available.

Sophia Meharena is on the frontlines of the crisis. A community physician with Every Child Pediatrics in Aurora, she has created an integrated model of care with behavioral health professionals based at her clinic. But most clinics can’t afford to implement that model because they don’t get reimbursed for mental health consultations. Meharena says the overall system is too reactive and needs to move more toward prevention. “We need to have a system that engages care givers, youth, the community, and primary health providers.”

Meharena joined the other healthcare professionals in calling on Governor Jared Polis to devote $150 million from the American Rescue Plan Act to youth mental health services. The coalition also wants the state’s congressional delegation to ensure that the Build Back Better Act includes $2.5 billion each year for five years in grants to children’s hospitals to increase their capacity to provide pediatric mental health services.

Meharena joined the other healthcare professionals in calling on Governor Jared Polis to devote $150 million from the American Rescue Plan Act to youth mental health services. The coalition also wants the state’s congressional delegation to ensure that the Build Back Better Act includes $2.5 billion each year for five years in grants to children’s hospitals to increase their capacity to provide pediatric mental health services.

Jenna Glover, director of psychology training at Children’s Hospital said the state’s mental health services system for children and youth needs to be completely rebuilt. “We are calling on the Colorado congressional delegation to take advantage of this generational opportunity to invest in a system that works for kids by strengthening the mental health workforce, building on the success of telehealth, and enhancing mental health insurance parity to improve access-to-care.”

Although the medical health professionals say elected officials need to take immediate action to fund these kind of mental health initiatives, they know that rebuilding the system won’t happen overnight. “The type of commitment that is going to be needed for long-term sustainable change is not going to be measured in months,” said Brumbaugh. “Long term investments in building or building out residential treatment facilities, that’s going to take years.”

Although the medical health professionals say elected officials need to take immediate action to fund these kind of mental health initiatives, they know that rebuilding the system won’t happen overnight. “The type of commitment that is going to be needed for long-term sustainable change is not going to be measured in months,” said Brumbaugh. “Long term investments in building or building out residential treatment facilities, that’s going to take years.”

That’s little comfort for the Central Park mother who worries every day that her daughter may do something to harm herself or others. “I love my kid. I just want to help the child that I know is inside before it’s too late.”

0 Comments