At the University of Colorado School of Medicine, students learn to be empathetic and caring doctors by understanding patients’ illnesses within the context of their lives. They do this through communication courses, which are integrated into all 4 years. Communication coaching in the preclinical years occurs mainly in small groups, but as students move into clinical rotations and come to demonstrate skills at the CAPE. Students are recorded doing role plays with standardized patients (actors), which are reviewed by faculty. Kirsten Broadfoot, communication skills specialist, and donnie betts, Standardized Patient Educator, discuss how medical students are communicating with their patients.

At a recent doctor visit after two weeks of feeling miserable, the doctor patted me on the back and said, “You’re definitely sick. I’m sorry.”

That simple gesture gave so much relief I almost hugged him. He understood and compassionately expressed he felt bad for me. I had never experienced such a human moment with a doctor before.

Along with diagnosis and treatment, doctors provide emotional support in what are often stressful times for patients. This dual role as social workers and medical providers is a more recent idea.

Search the National Library of Medicine and a slew of articles pop up about the growing importance of physician communication and “emotional intelligence.”

“We think communication is a key skill in being a physician and healing and sharing people’s lives,” Dennis Boyle says. He has helped develop the communication program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

When Boyle went to medical school in the ’70s, empathy wasn’t a valued skill in medicine. He remembers one slide about it: “Be nice to patients.” He now teaches practicing physicians, who like himself never learned it in medical school, how to communicate and connect emotionally.

“It’s about taking the communication techniques and building them into your style. It’s not just a thing you do, it’s a part of you,” Boyle says.

At CU, communication is taught with rigor from day one and continues throughout the four years. Some students from day one can naturally communicate and express compassion; others have compassion, but struggle showing it; and some, though not uncaring people, only speak in clinical terms.

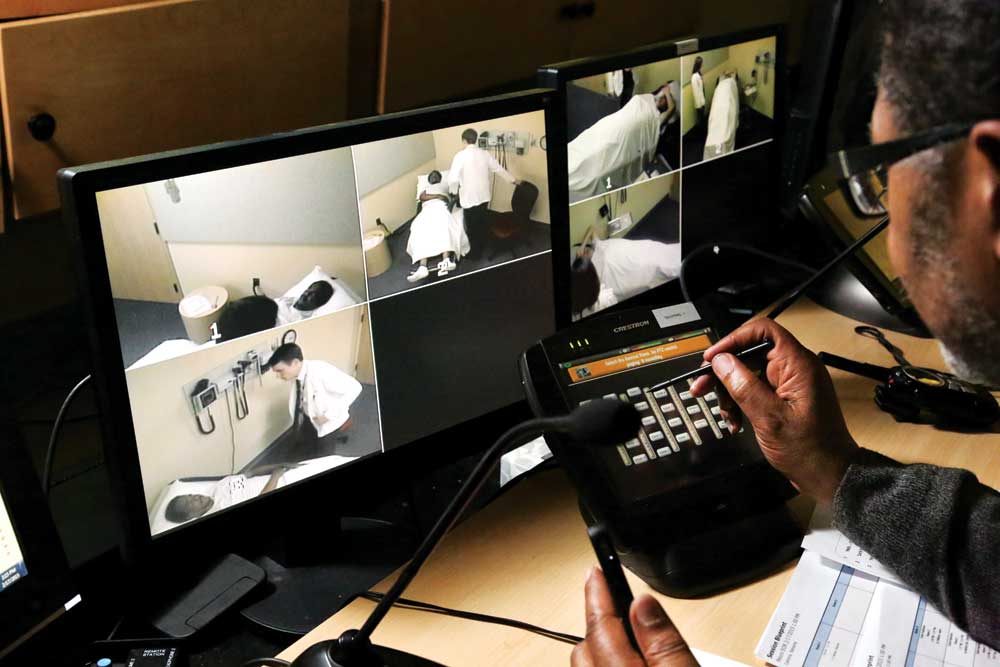

Standardized Patient Educator donnie betts is able to control camera angles so communication coaches can observe every part of how students interact with patients.

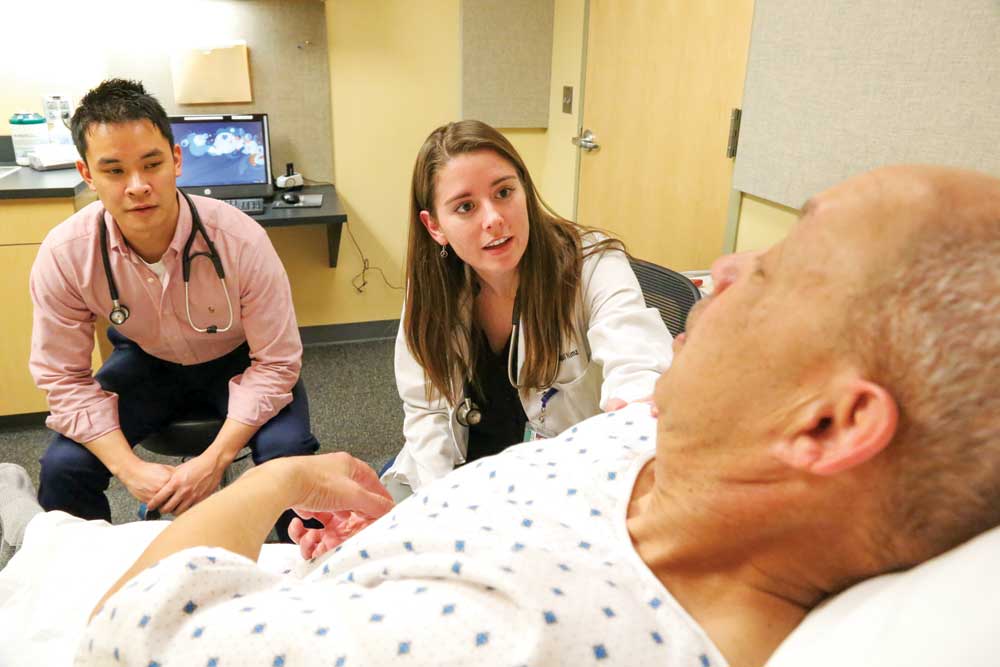

Medical students Paul Tran (left) and Abby Nimz are recorded diagnosing and treating Standardized Patient Donahue Hayes, who is re-enating a stroke.

Tran diagnosing the severity of Hayes’ stroke. In addition to diagnosing and treating illnesses, students are taught to provide emotional support in often stressful situations like this.

Associate Director of Communications Deborah Seymour believes medical school can help students learn to be caring and understand illnesses within the context of patients’ lives.

CU uses the Calgary-Cambridge approach, a set of 72 skills on how to hear a patient’s story and respond “empathetically, clinically, humanly and professionally.”

Students practice communication at the school’s Center for Advancing Professional Excellence (CAPE)—a simulated (but very convincing) clinical setting equipped with manikins that have pulses and make breathing sounds. There are 15 outpatient exam rooms, three consultation rooms, and three simulation rooms that can be transformed to look like an ER, inpatient hospital room, labor and delivery suite, or operating room. Most of the simulation rooms in the Rocky Mountain region are gathered on this campus.

Students are filmed interacting with standardized patients (actors) while communication coaches watch in real time from a control booth. Afterward they give feedback including everything from eye contact to body language to providing clear information.

The communication skills can be adapted to all clinical settings.

Kirsti Broadfoot is a communications skills specialist at CAPE and implemented the Calgary-Cambridge approach in 2012. She coaches students how to strike the right balance between social worker and medical provider. How an individual finds that balance cannot be predicted and it shifts. “Medical school is about creating a person,” she says.

While she always wants students to be empathetic, she is conscious of their personal lives and how tiring it can be in the current healthcare setting. Doctors don’t have enough time to see patients, get the diagnosis, prescribe treatment and then give emotional support. Burnout is a big problem.

Because of the time crunch, doctors may revert to teaching mode and try to share as much information as possible. At the end of giving this information, there is no time left to provide patients emotional support.

These types of doctor’s visits stick out to Michael Rudolph. At age 3, he had lymphoma, which was cured, but he has experienced residual health effects into his adult life. At times he’s felt like doctors don’t listen or believe what he’s experiencing.

These “bad doc” experiences drew him to medicine and inspired him to be the “good doc.” He is now a fourth-year med student at CU. “It’s easy to get lost in the medicine and the science, and trying to get the right diagnosis and all the right tests,” he says. “Obviously that’s important, but I think that when you get so heavily into that you seem to forget that ultimately there’s a person who you are doing all this stuff for.”

Nearing the end of his schooling, he is still in medicine for the same reason—simply to help people. He tries to keep his patient experience in mind. Interacting with people and experiencing human moments, like a pat on the back, continue to make the profession fulfilling.

0 Comments