Hanging in gorgeous gilded frames is DAM’s first comprehensive exhibition of France’s impact on American painting. Curator Standring said there’s a connective tissue throughout the entire exhibition, so when people view one painting and then the next, they say, “Oh, I get it now.”

Hungry for artistic technique and eager to make a name for themselves, ambitious American artists flocked to France from 1855 to 1913. Denver Art Museum’s (DAM) latest exhibition: Whistler to Cassatt: American Painters in France, which opened Nov. 14, follows the work of these artists in more than 100 paintings.

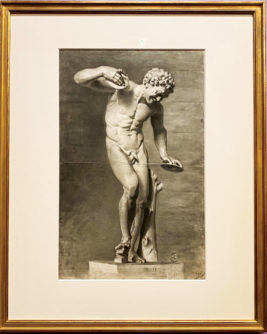

John Singer Sargent drew “The Dancing Faun” when he was only 18. It secured his placement in Carolus-Duran’s prestigious studio. Later he painted Carolus-Duran, an homage to his master.

Aspiring artists recognized that studying abroad was essential to their careers, says DAM’s Curator Emeritus Timothy Standring. Art schools in the U.S. weren’t as sophisticated as those in France. American students could have gone to Dusseldorf, to Munich, to Rome, to London, but most of them went to Paris—then considered the center of the art world. In Paris, they could experience the complexity of French painting from traditional academic paintings to canvases showing strains of realism and impressionism. American artists observed, experimented, and learned in the private studios of famous French painters or at the state Académie des Beaux-Arts. The curriculum included copying reliefs or plaster casts of classical sculptures and drawing and painting the human figure from life models. Many students were also required to copy and study at the Louvre once a week.

France offered another draw—the Paris Salon. The Paris Salon was an official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was arguably the most esteemed annual or biannual art event in the western world from 1748 to 1890. To be featured in the Paris Salon not only solidified your standing in the art world, it also meant you would be featured in the likes of New York Times Magazine, an accomplishment that meant your work was worthy of purchase and a springboard that catapulted many artists from starving to successful.

Standring anticipates “Mother and Child” by Mary Cassatt, which captures a tender moment between a mother and her sleepy toddler, will be a big draw for art enthusiasts.

When they weren’t studying, American artists and their French colleagues congregated in artist colonies to which some returned faithfully every year and others never left. They sketched together in the French countryside, and some of their works featured prominent academic figures placed in picturesque Parisian landscapes.

The French art world was neither a level playing field nor completely exclusionary. Women weren’t allowed to join the Académie des Beaux-Arts until 1897, and even then they attended separate classes. They also weren’t allowed to sketch nude male models. However, they were allowed to enter competitions and often walked away with the top prizes. Mary Cassatt achieved her first critical acclaim in 1868 when her “Mandolin Player’’ was accepted for that year’s salon. One critic wrote, “The French were wild over her.” Another said, “Babies, my God! How their portraits have repeatedly horrified me! A whole sequel of English and French daubers painted them in such stupid and pretentious poses! For the first time, I have, thanks to Miss Cassatt, seen the effigies of ravishing youngsters, peaceful and bourgeois scenes painted with a kind of delicate tenderness, all charming.”

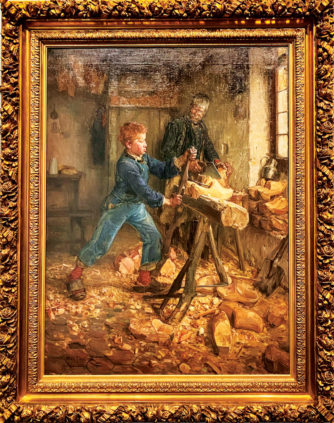

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the first African American man to submit a painting to the Paris Salon; he achieved international acclaim for “The Young Sabot Maker” in 1895.

African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner strove to master the single male nude evidenced in his piece, “Study of a Negro Man.” He eventually won a third-class gold medal and elicited high praise from critics. He was the first African American man to be submitted to the Paris Salon, about which he said, “In Paris no one regards me curiously. I am simply Mr. Tanner, an American artist. Nobody knows or cares what was the complexion of my forebears. I live and work there on terms of absolute social equality. Questions of race or color are not considered—a man’s professional skill and social qualities are fairly and ungrudgingly recognized.”

Upon returning home, many artists were criticized for honing skills that lacked “Americanness.” Having earned their place in the Paris Salon, several artists were disappointed to be excluded from New York’s National Academy of Design exhibition. So ten of them, eventually dubbed “The Ten” by the media, created their own collection, cohesive in theme and direction, and showcased it on their own. Later, a group called, “The Eight” followed suit asserting that each artist had the right to craft a completely individual approach to his or her stylistic inclinations.

“In this exhibition, visitors will experience the stories of renowned American artists, their challenges, triumphs, and learnings in the region [and how they] contributed to the fluorescence of this period’s paintings,” says DAM Director Christoph Heinrich. “By advancing narratives that reveal the deep cultural links between France and America, DAM’s exhibition provides audiences with a more comprehensive understanding of one of the most complex periods in American art history.”

Whistler to Cassatt will be presented in the Anschutz and Martin and McCormick Galleries on level 2 of the Hamilton Building through March 13, 2022. Entry requires a special ticket. For more information visit https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/exhibitions/whistler-cassatt.

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments