From the Crawford Hotel mezzanine level, Dana Crawford looks over the Denver Union Station great hall that she considers “Denver’s living room.” She is the subject of a new biography by Mike McPhee titled, Dana Crawford: 50 Years Saving the Soul of a City.

On a bench in the “great hall” of Denver Union Station sits Dana Crawford, on her cell phone, conducting business. Seeing her interviewer approach, Crawford hands the phone to her associate, who comments, “Wherever Dana is, that’s her office.”

We are meeting in what she likes to call “Denver’s living room—do you know it’s open 24/7 and never locked?” The bench is just across from the lobby of the Crawford Hotel, named in her honor and in recognition of her 50 years of work revitalizing Denver. It’s a mission she continues as head of Urban Neighborhoods, a real estate development company she founded in 1988. She shows no signs of stopping, with numerous projects underway and apologizes for cutting short the interview.

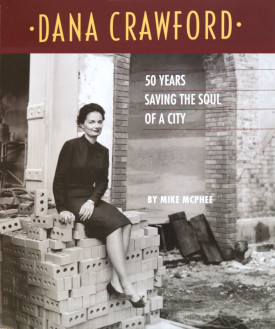

Fortunately for all of us, Mike McPhee has summarized Crawford’s importance to Denver in a highly readable, beautifully illustrated book, Dana Crawford: 50 Years Saving the Soul of a City (2015 Upper Gulch Publishing Co.). McPhee is a retired Denver Post reporter who has launched a second career as a biographer.

McPhee claims Crawford is the “most quoted woman in Colorado history.” A partial list of her accomplishments suggests why:

- Creator of Larimer Square in the mid-1960s at a time when all development trends were spinning out to the suburbs

- Developer of the Oxford Hotel

- The person who brought industrial warehouse loft living to Denver

- Charter member of Historic Denver

- Recipient of the highest award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Leader of the partnership that re-developed Denver Union Station (DUS)

She was such an early leader in historic preservation, she put Denver on the map—consulting nationally on how to link legacy buildings with urban revitalization. She was 50 years ahead of today’s millennials and their affinity for urban living. And sitting today in the DUS great hall, she worries that when commuter rail opens for service next April, the place will get overcrowded. Being practical and a visionary, she can foresee that the bathrooms in RTD’s bus concourse and in DUS will not be adequate. Despite the concern, she still wants A Line riders to hop on the train and get acquainted with DUS and all that LoDo has to offer.

She was such an early leader in historic preservation, she put Denver on the map—consulting nationally on how to link legacy buildings with urban revitalization. She was 50 years ahead of today’s millennials and their affinity for urban living. And sitting today in the DUS great hall, she worries that when commuter rail opens for service next April, the place will get overcrowded. Being practical and a visionary, she can foresee that the bathrooms in RTD’s bus concourse and in DUS will not be adequate. Despite the concern, she still wants A Line riders to hop on the train and get acquainted with DUS and all that LoDo has to offer.

McPhee’s book makes a strong case that Crawford’s legacy is nothing less than a healthy Denver. Those with an historical perspective know what Denver was like 50 years ago and that things could have gone very differently absent leaders like Crawford.

McPhee’s book traces Crawford’s small town, central Kansas upbringing on to junior college, Kansas University and to graduate business school at Radcliffe. This was a time when women weren’t admitted to Harvard even though “we took the same classes from the same professors and studied the same cases as the Harvard Business School.” That kind of gender bias was undoubtedly formative in shaping the hard-nosed businessperson she became, a reputation that McPhee addresses in his book. Internships in Boston and New York acquainted her with urban living. After graduation, at a friend’s suggestion, she moved to Denver and soon wrote to her mother, “After New York, everyone here is so damn nice. I LIKE Denver.”

Landing a job in public relations, she was soon introduced to city leaders and took on a high-profile assignment to “help sway public opinion about ‘Big Bill Zeckendorf,’” an eastern developer with a disdain for suburbia and big plans for Denver’s future (he eventually built the I.M. Pei-designed May D&F department store and plaza at 16th and Court Place as well as numerous other projects). Experiences like that, plus memories of Boston’s Back Bay and New York’s Greenwich Village, and exposure to Aspen’s revived 19th-century Victorian mining town ambience began to coalesce in the back of Crawford’s mind even as she raised four boys and continued with her consulting career.

Seeking to be a developer herself, eventually she settled on redevelopment of the 1400 block of Larimer Street, a place steeped in Denver’s pioneer history but better known by the 1950s as the city’s skid row. Countering the prevalent trends in urban renewal, she brought in “rebuilding crews” instead of wrecking crews. She set out to “transform a shabby district into a handsome and useful one … it will contain the nucleus of Denver’s nightlife.” She attracted investors, assembled parcels, refurbished buildings, vetted potential tenants and in 1965, welcomed the world to “Larimer Square.”

Author Mike McPhee, who wrote Dana Crawford’s biography, sits with her at Union Station near the Crawford Hotel.

This lively, mixed-use district of older buildings formed a distinct contrast to the acres of vacant properties and parking lots elsewhere in LoDo created through the building demolitions facilitated by the Denver Urban Renewal Authority’s 27-block Skyline project. Through Crawford’s tenacity, Larimer Square itself had been saved from demolition when it was granted an exemption from DURA action and protected as a “rehabilitation area.”

The rest, as they say, is history—but one that continues to play out today in Denver. McPhee sees Crawford’s work as the crucial first step in revitalizing Denver as a thriving core city and showing the way to others across the country. He notes the impressive series of Denver mayors who “imagined a great city” and then went out and did something about it. He recounts Mayor Federico Peña’s shock at finding that the 4,600 acres of the Central Platte Valley in the early 1980s contributed a grand total of $40,000 in property taxes to the city. Crawford herself says that Peña doesn’t get enough credit for the vision and effort he brought to transforming Denver.

However, it is clear from the numerous testimonials in McPhee’s book that city leaders in the know believe that it all started with Crawford. Peña: “Dana was truly a visionary. She set up historic preservation in Denver. There’s no one else like her.” Wellington Webb: “Dana’s hands are on everything in this city … So many of her projects were ones that everyone else gave up on and said they couldn’t be done.” John Hickenlooper: “Dana had the foresight and the appreciation of what those buildings had to offer, that no one else at the time seemed to have … She single-handedly saved lower downtown Denver.”

McPhee notes that Crawford was so far ahead of the market that it diminished her personal financial returns. The example he gives is the requirement by banks that she pre-sell residential loft units because they had so little confidence in her warehouse renovation projects. This prevented her from profiting from the units’ price appreciation. McPhee writes, “By all appearances, she’s financially fit and comfortable but without the extensive holdings of the most successful real estate developers.” McPhee said it’s unfortunate that our society tends to measure success in dollars because Crawford is a true success who cares more about doing things right.

Crawford ended our interview by mentioning her involvement in 18 separate projects at the present time. Now in her mid-80s, she admitted to working more than fulltime. Many of her projects are still downtown but she has branched out to help the City and County of Broomfield fashion their own downtown with a project at First and Main. She also said she has been contacted by the owners of the Argo Mine near Idaho Springs. With a twinkle in her eye, she said she is considering a hotel and restaurant project at the mine itself, her latest venture in making something new and better out of something older and undervalued.

0 Comments