Artist Edgar Degas experimented with new art mediums and techniques in his ‘attic laboratory’ overlooking Paris. The recreated studio lets visitors look over the artist’s shoulder into the processes of this restless scientist-artist, who was never satisfied and never finished. “Fortunately for me, I have not found my method; that would only bore me,” Degas wrote.

Degas is best known for his paintings of ballet dancers, but his palette of subjects was much broader, as was his range of artistic mediums. Degas: A Passion for Perfection, at the Denver Art Museum through May 20, opens our view of the famous artist and his personality. The exhibition covers a period of 60 years and includes Degas’s early historical scenes, his studies of horses, and his fascination with the nude—as well as his most familiar depictions of dancers.

Dance Examination, 1880. Degas captures the moment when two dancers are about to audition. One adjusts her stocking, while the other focuses on positioning her legs and feet.

“This exhibition is all about what people don’t know about Degas,” said Timothy Standring, Gates Family Foundation Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the DAM. The more than 100 works on display include paintings, drawings, pastels, etchings, monotype and bronze sculptures.

The presentation also serves as an introduction to the man behind the art. “Edgar Degas (1834-1917) was a man and an artist full of contradictions,” Standring said. “He was artistically radical, yet politically conservative. He had some training but could also claim to be self-taught. Fiercely independent, he exhibited with the Impressionists but refused to be labeled as one.”

To see print article, click here: Degas at DAM

A man of contradictions

The contradictions in Degas’s life and work come to light in his own writings, splashed on the gallery walls, including this quote: “I should like to be famous and unknown.”

The Denver Art Museum is the sole American venue for Degas: A Passion for Perfection, showcasing the prolific French artist’s works from 1855 to 1906. Visitors will get an intimate look into his creative process as well as his life.

“Crude and often cold, Degas was known as a curmudgeon with a sharp wit,” said Standring. “But he was also a poet, once writing that dancers had sewn his heart ‘into a pink satin bag, slightly faded satin, like their ballet shoes.’”

Degas’s artistic journey becomes evident as the visitor walks through the exhibition. From his early studies to his masterworks, Degas’s various motifs emerge. “He studied the old masters and even copied their paintings,” said Standring. “He studied figures, as all the artists did, at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and his first nudes are on display here. We see some of his plein air [outside] work, including small panels depicting the family villa in Naples.”

Horses, especially the movements of horses, were a fascination for Degas. He studied early films of running horses and captured the movement in bronze sculptures and paintings of races. “He was interested in movement, not static images,” said Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Mayer Director of the DAM.

Capturing the moment

His “bathing women” series, including works in pastels, charcoal and bronze sculpture, was intended to convey not only movement but immediacy. “He was capturing the moment; he was not interested in the next 150 years of viewers,” said Standring. “But it speaks to how infectious these works are, that we still talk about them.”

Degas was an innovator who experimented constantly with his materials and techniques. “He blurred the boundaries of traditional media and pushed them to extremes,” said Standring. “In order to imitate flat Italian painting, he invented an oil medium known as l’essence, in which the oils in oil pigment are leached out and then mixed together with paint thinner. Sometimes he used oils like watercolor, making them liquid-y, or he added water or oil to pastels, to blur the line between painting and drawing.”

Degas experimented extensively with monotype printmaking, in which pigment is applied to a smooth plate and then transferred to paper using a printing press. He frequently reworked the printed images with pastels. “Later in his life his family needed money, so he produced and sold a number of monotypes,” said Standring.

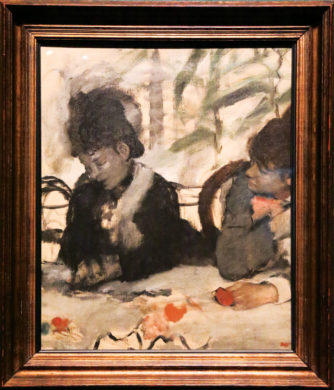

At the Café, about 1875-77. Degas’ focus on the women’s conversation is evident in his sketchy rendering of the foreground and the moving crowd in the background.

A restless artist

The artist repeated his subjects—horses, bathers, dancers—again and again, continually experimenting and making adjustments. “The viewer is engaged in his process,” Standring said. “He was obsessed with the repetition of making; he did not want to stop. He was a restless artist—never satisfied and never finished. Perfection, defined only on his terms—was a constant pursuit and elusive reward.”

Visitors enter the exhibition’s final, ballet-themed gallery through a mirrored hallway with a barre (handrail), evoking a dance studio. The showing includes some of Degas’ most iconic images, including Dance Examination (in the DAM collection), the large-scale Dancer with Bouquets and The Dancing Lesson, an example of his pastel-over-monotype technique.

“He was interested in the reality of the dancers’ experiences, not just the fantasy,” said Standring. “Like Degas, his dancers dealt in contradictions—beauty and pain, grace and vulgarity, playfulness and discipline.”

For more information and tickets, see denverartmuseum.org or call 720.865.5000.

0 Comments