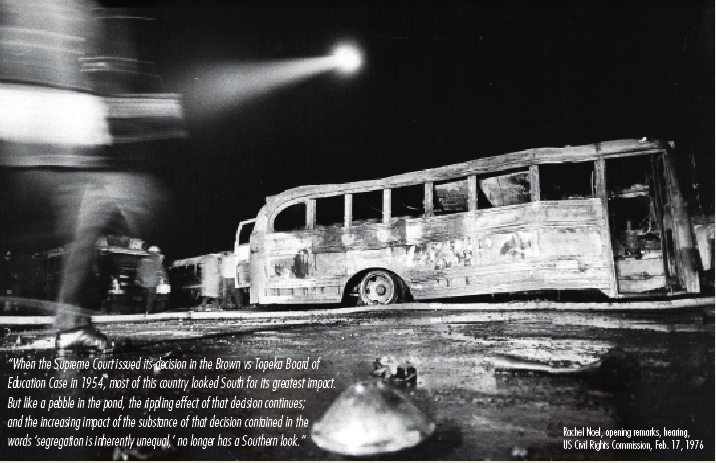

In 1970, 12 dynamite bombs destroyed 24 school buses and damaged an additional 15 at a DPS bus depot; the New York Times referred to this as a “massive and skillful demolition job.” Witnesses reported seeing three young White males fleeing the scene. DPS had been ordered to purchase new buses the year before to facilitate busing. To date, no one has been convicted. That same year, the Keyes family found a bomb outside their home; fortunately, no one was injured. Photo by Steve Larson for the Denver Post (now publisher/photographer for the Front Porch).

Brown v. Board of Education originated in a class action lawsuit filed by residents of Topeka, Kansas who wanted to be able to choose the school their children attended. The landmark 1954 decision represented an about-face for the Supreme Court, which in 1896 had approved Jim Crow segregation by sanctioning “equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races.”

Still, the 1954 decision lacked teeth and could not transform centuries of racism into acquiescence. In many cities, violence ensued as communities and officials resisted the mandate. The Little Rock Nine who bravely integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957, for example, did so at profound personal risk. President Eisenhower had to call upon the Arkansas National Guard and sent 1,000 paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division to protect the students and restore order.

In the decade following Brown, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in numerous cases against de jure segregation (segregation written into law), banning segregation in public accommodations from restaurants to golf courses to beaches.

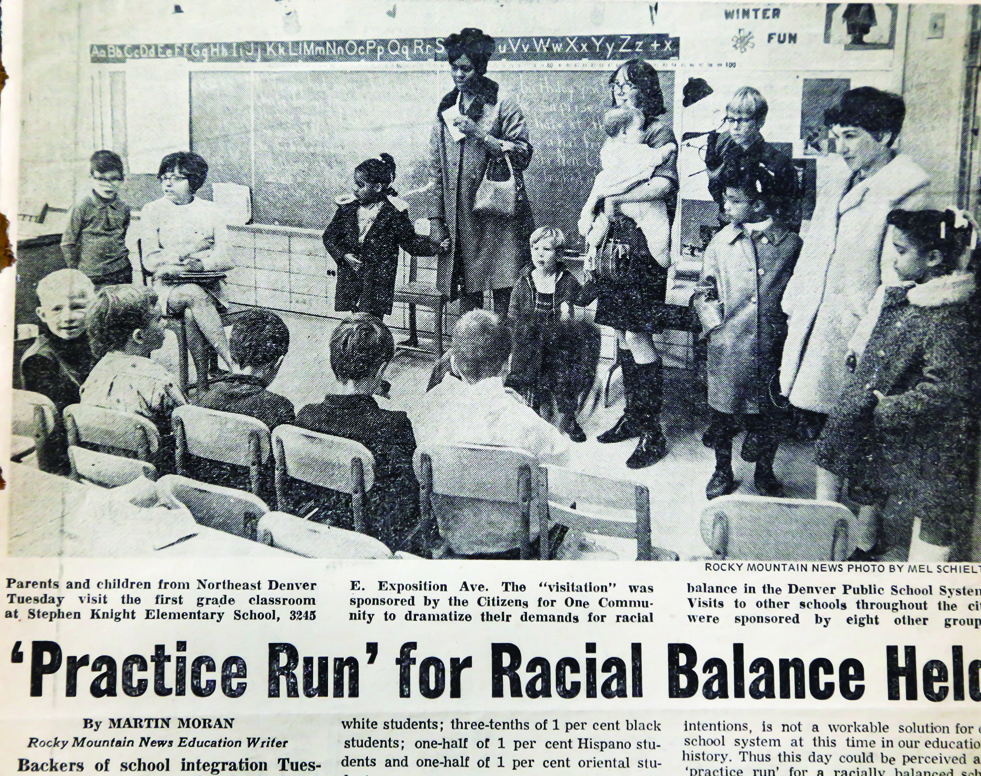

Helen Wolcott (right) and Anna Jo Haynes’ daughters, Lee Ann and Mary, visit Stephen Knight Elementary, 3245 E. Exposition Ave., in 1969. The visit was sponsored by “Citizens for One Community” that supported school integration. At the time, Stephen Knight Elementary, now Knight Center-Early Education, was 98.7% white. Today it is 68% white.

Segregation in Denver Public Schools

In Denver, de facto segregation (segregation in practice) was every bit as nefarious as de jure segregation. And because it was not codified, it endured long after Brown and subsequent Court decisions.

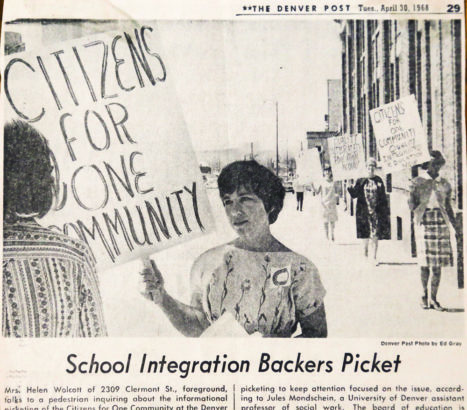

Helen Wolcott talks to a pedestrian about school integration outside the Denver School Administration Building in 1968. She and fellow picketers demanded DPS make a plan for integration.

As demographics in Northeast Park Hill shifted from 3% to 70% African American between 1960 and 1967, locals watched national events with increasing anxiety, fearful that the volatile combination of civil rights protests, unemployment, alcohol, drag-racing youth at the Dahlia and Holly Shopping Centers, and summer heat would erupt in violence. As it turned out, Denver’s de facto segregation would be what put the city at the forefront of the national civil rights scene as the 1960s waned. What Brown v. Board of Education represented for de jure segregation in 1954, Keyes v. School District No. 1 symbolized for de facto segregation in 1973.

Notwithstanding a 1959 Fair Housing Law in Colorado, redlining and other discriminatory practices meant that neighborhoods and schools in Denver were extremely segregated. For years, the school board continued drawing school boundaries to safeguard segregation. Denver’s Black population, which was growing in the 1950s, increasingly exerted pressure on DPS to provide all children quality education. The result was several committees that examined schools’ racial and ethnic composition, boundaries, and other considerations.

A 2016 photo of Helen Wolcott (left) and Anna Jo Haynes taken by Steve Larson for the Front Porch. Newspaper clippings are from Wolcott’s scrapbook.

Due to changing demographics, Park Hill was the subject of particular concern, especially when DPS in 1960 built Barrett Elementary (near Colorado Blvd. and 29th Ave.). The school seemed to have been erected deliberately to exclude its predominantly Black student population from the much better-equipped White Park Hill Elementary School. Within a few years, the Office of the Mayor’s Commission on Community Relations reported that Northeast Park Hill’s two elementary schools were “de facto segregated”—and the junior high school was “integrated, but changing very rapidly into a de facto segregated school.”

The same report concluded “The Negro community of Denver is essentially separated and/or alienated from the majority white community in Denver. There is not equal opportunity for members of the Negro community in areas of employment, education, housing or recreation.” (Aug. 31, 1967, Rachel Noel Papers at Blair-Caldwell Library).

DPS Integration Plan

Undaunted by harassing phone calls, in 1968, the Denver school board’s first Black member, Rachel Noel, introduced a resolution directing the superintendent to submit to the board a comprehensive plan for school integration. The following year, however, voters elected anti-integrationists, who quickly rescinded Resolution 1490 (the Noel Resolution). Civil rights attorneys and eight Denver families decided to move forward with a lawsuit, with Park Hill’s Lylaus and Wilfred Keyes family serving as lead plaintiffs. District Judge William Doyle’s ruling in favor of the plaintiffs began the case’s trajectory to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In his 1973 majority opinion, Justice William Brennan wrote that the school board was guilty “of following a deliberate segregation policy at schools attended, in 1969, by 37.69% of Denver’s total Negro school population, including one-fourth of the Negro elementary pupils, over two-thirds of the Negro junior high pupils, and over two-fifths of the Negro high school pupils.” To remedy the situation, DPS launched mandatory school busing, triggering widespread White flight.

Melba Pattillo Beals, one of the Little Rock Nine, writes in her 1994 memoir, Warriors Don’t Cry.: “The effort to separate ourselves whether by race, creed, color, religion, or status is as costly to the separator as to those who would be separated.” Her words are just as potent today, as we reflect on over half a century of missteps in the struggle for desegregation and consider not only what Brown and Keyes meant, but where they fell short and how we can achieve true and meaningful integration for our children and grandchildren.

Hi Martina, I’m a student of Architecture and Urbanism, I’m currently doing a research on urban-social segregation in Latin Americans living in the Summit County area. I found a blog in which you talk about segregation in Colorado, just the state of my study. So, I would like to do a short interview with you or I could have reference to your research, holding it as a reference author. I look forward to your prompt response.

Well worth a read. Got great insights and information from your blog. Thanks.