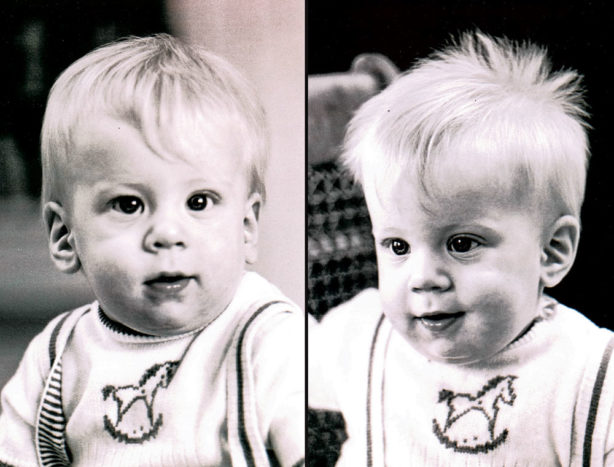

Identical twins Stephen and Peter Nash as babies. Photo courtesy of Stephen Nash

I have a clone.

He’s an identical twin brother, really. But as monozygotic twins derived from one fertilized egg, we share the exact same genome.

Since birth, we have been engaged in an inadvertent experiment to test whether nature (genetics) or nurture (culture) is more important in an individual’s development. As with any dichotomy, the reality lies not in the extremes but somewhere in the middle: Nature and nurture are important to an individual’s development.

That said, if nature were the more important force, we’d expect identical twins to be really similar people—physically, socially, psychologically, and otherwise. If nurture were more important, we would expect identical twins to end up as very different people.

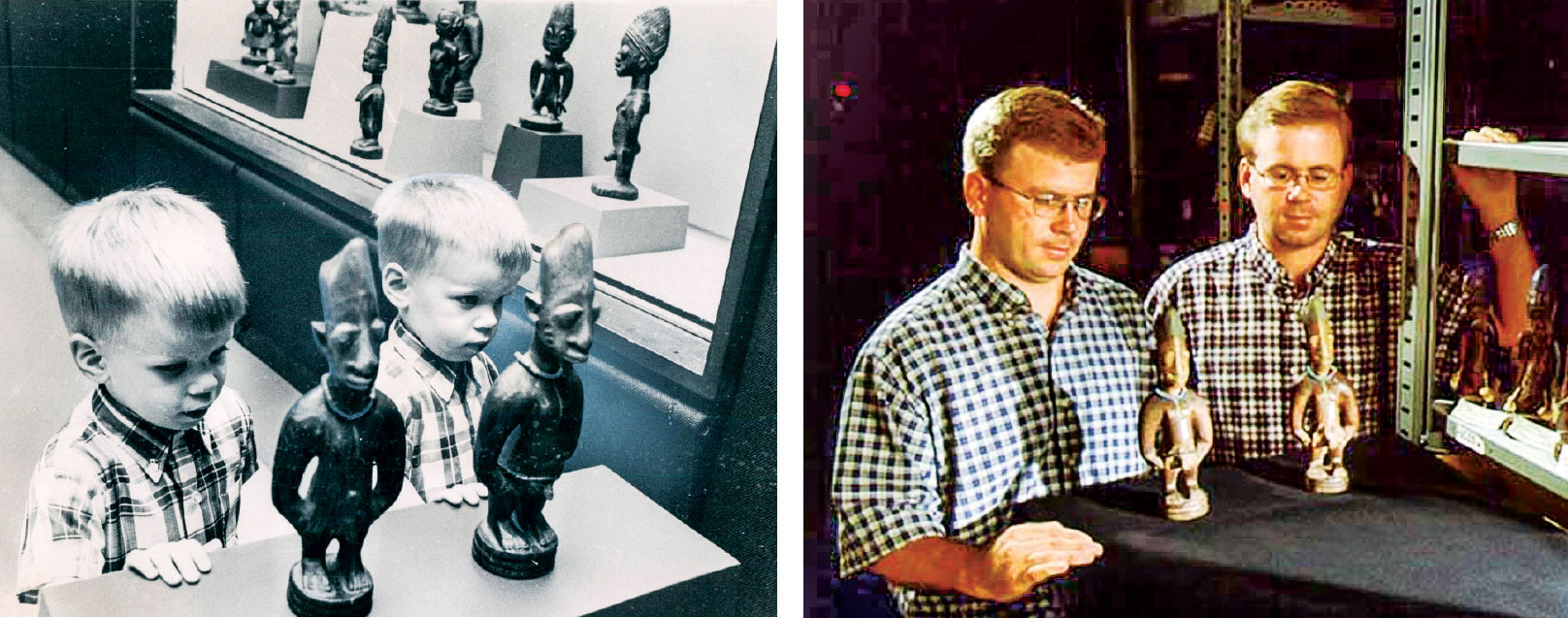

While working as Head of Collections in Anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago, Steve Nash realized the ibeji collection triggered a memory. His mother confirmed his recollection and pulled out the childhood image (above left) of Steve (left) and his brother Peter looking at ibeji twin statues. The brothers recreated the photo as adults, surprising their parents when they saw it in the museum’s magazine. Left photo: STM-037871176, by John Lenahan/Chicago Sun-Times. Right photo: © The Field Museum, GN89822_4c, Photographer Mark Widhalm

Twins make for a fun existential thought experiment—one that philosophers, anthropologists, theologians, biologists, and parents have pondered deeply through the ages. In some parts of the world, such as in southwestern Nigeria, rich cultural traditions about twins have emerged over time.

As a twin, a parent of twins (you read right: fraternal boys), and an anthropologist, I’ve thought a lot about how people around the world understand the phenomenon of twinship.

In the Yoruba culture in Nigeria, artists were commissioned to carve ère ìbejì, statues of twins, when one or both of a set of twins died.

© Denver Museum of Nature & Science

My brother and I were born in Hyde Park, a neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, in 1964. Our mother was an admissions counselor at the University of Chicago; our father was an editor at the Field Museum of Natural History. Their primary network of friends consisted of anthropologists and other scholars from those institutions, as well as an eclectic, steady stream of students, postdocs, and young faculty members who came through the university.

At that time, Hyde Park was known for its social and political activism and for the scholarly atmosphere offered by a world-class university in a diverse, cosmopolitan city. Although our folks were not full-blown hippies, they were strong supporters of the anti-war, civil rights, and women’s liberation movements.

Our parents were also keen readers of Dr. Benjamin Spock’s influential book The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care. (Now in its revised 10th edition, the book has since been renamed Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care.) Spock confidently told nervous new parents: “You know more than you think you do,” and “trust your own common sense.” He advised them to take a more laissez-faire approach to parenting than their own parents likely had and suggested they shower their children in permissive affection. (Conversely, he also advocated corporal punishment.)

Following on Spock’s advice, my parents encouraged my brother and me, from birth, to establish our own identities. On the surface, we were (very) identical twins, but the message from our folks was clear: Be your own person.

Steve Nash and his wife Carmen Carrasco live in Park Hill with their children (from left) Ben, age 17, who attends East HS and twins Thomas and Charles, age 13, who attend McAuliffe International School. Front Porch photo by Christie Gosch

Looking back, we may have taken that advice to its extreme—we often defined ourselves as the antithesis of the other. I went to Grinnell College and went politically further to the left; he went to Macalester College and took a hard turn to the political right. I became an anthropologist; he went into finance.

Nurture ate nature for lunch.

I now serve as the director of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS). In June, we obtained a National Endowment for the Humanities CARES grant to keep members of the department employed during the economic downturn resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. That grant specifically provided funding for us to conduct research on the World Ethnology Collections, which include a small but significant collection from Africa. Given that we don’t have an African collections expert on staff, I volunteered to accept the charge.

As I went through cabinets full of baskets, masks, textiles, and other artifacts, I spotted a pair of exquisite wooden statues, roughly 12 inches high. They looked vaguely familiar to me, but I couldn’t remember why.

One statue is biologically female, the other biologically male. They look like fraternal twins because of their similar expressions, hairstyles, jewelry and accoutrement, stances, and decorative pigments. Their arms and legs are bent as if engaged in (or poised for) some action, perhaps a dance of some kind. The gaps between their torsos and arms add to their depth and dynamism; they are clearly meant to be seen in the round.

A quick review of our files confirmed my suspicions. The statues are Yoruba twin statues, or ère ìbejì. Usually between 6 and 12 inches high, ère ìbejì come in a great variety of styles.

Yoruba women in southwestern Nigeria have one of the highest rates for twin births in the world. Between 4 and 5 percent of all Yoruba births yield dizygotic (fraternal, or two egg) twins compared to a rate of between 1 and 2 percent for births in other societies. Scientists have been unable to explain why this population’s twinning rate is so high, but one theory—by far my favorite—is that a diet high in yams might be to blame. (I’d like to think my brother and I are the result of some dietary quirk of the early to mid-1960s. Anyone up for a glass of TaB or Tang, perhaps?)

Sadly, Yoruba artists were once commissioned to carve ère ìbejì when one, or both, of a set of twins died. As surrogates for the deceased, the ère ìbejì were carried by the mother of the twins; she fed and cared for them as if her babies were still alive. She did so because some Yoruba understood that twins, in addition to being sacred and powerful, shared a soul. If one twin died, that collective soul was then out of balance, hence the need for a stand-in.

Some ère ìbejì display distinctive wear patterns, particularly on their faces, demonstrating that their mothers actively cared for them for years and, in some cases, decades.

After working with these statues for a time, I finally realized why they looked so familiar to me. My brother and I spent some time with a similar set of statues when we were very young.

In 1967, before our third birthday, the Field Museum presented an exhibition of 68 pairs of ère ìbejì.

My father, then working in the museum’s public relations department, thought it would be cool to stage a photograph of us with a set of ère ìbejì. (Even though our parents made every effort for us to be different, they, and we, occasionally took advantage of our twinship.) The resulting photograph ran in the July 7 issue of the Chicago Sun-Times under the headline “Chicago Twins Meet Yoruba Twins.” I look at it from time to time, amazed that we were that identical as children.

Now, years later, the photograph reminds me that cultural diversity is a wonderful thing. People may be born in different times, in different places, and with different technologies, but we are all humans who have to address issues like life, love, and death. Through culture, humans address those issues in a myriad of ways. As one of my students wrote long ago: “The epic sweep of humanity is indeed mighty cool to behold.” He was right.

What, then, does it mean to be a twin?

Honestly, I’m ambivalent about it. Growing up, I enjoyed always having someone of the same age available to play with, but that meant there was always someone around to fight with as well.

I can’t really say what it’s like to be a twin because I don’t know what it’s like not to be a twin. Most of the twins I know—and I know a surprising number of them—were raised, like my brother and I were, to be different. Our identities and our public personas do not focus on our twinship. We cannot engage in telepathy, as some twins claim to do. Our interests, feelings, and emotions are often more divergent than identical.

And we don’t, like some Yoruba twins, share a soul. Sometimes I wish we did.

Stephen E. Nash is a historian of science and an archaeologist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. His expertise includes dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), the history of museums, the archaeology of west-central New Mexico, and Russian gem-carving sculptures by Vasily Konovalenko. Nash has published numerous books, most recently Stories in Stone: The Enchanted Gem-Carving Sculptures of Vasily Konovalenko and An Anthropologist’s Arrival: A Memoir. Follow him on Twitter @nash_dr.

This article was originally printed on Jan. 12, 2021 in the Anthropology Magazine Sapiens.org.

0 Comments