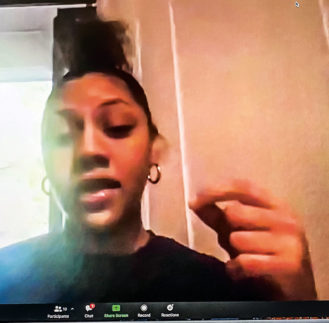

East High School teacher Matthew Fulford engages constitutional law students in a Zoom discussion about voting rights and other constitutional questions. Voting rights, for example, are not explicitly enumerated in the U.S. Constitution—and states are given lots of power over how to implement and interpret those rights based on the 14th and 15th Amendments.

![]()

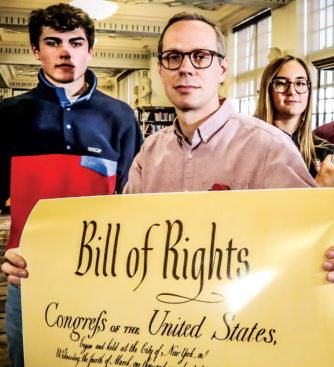

East High School constitutional law teacher Matt Fulford, pictured in East’s library, recently engaged his students in a discussion of current constitutional questions, including voting rights and the Electoral College.

As Denver voters mull over six long pages of candidates and ballot initiatives and wonder “Where do I find out about all these judges?” a group of East High School students is discussing big picture questions such as the franchise itself and the strengths and weaknesses of the Constitution. Following one such discussion, the Front Porch asked Colorado Rep. Jason Crow (D-06), whose name is also on the ballot as he seeks re-election, to reflect on the students’ ideas and other issues relating to our democracy.

The Limits of the Franchise

“Nowhere in the U.S. Constitution, other than in the amendments, is there an explicit declaration of the right to vote,” observes social studies teacher Matthew Fulford. He asks students what provisions—if any—imply a right to vote, and how suffrage has both expanded and contracted over time. Fulford teaches an AP Government and Politics (“Con Law”) class that competes in—and often wins—national contests; he brought students together via Zoom to share their thoughts.

“The Electoral College threatens democracy,” says Kari Jackson, who would like to see an end to what she believes is a biased institution.

Though not yet old enough to vote, these students are well-informed about the power and the limits of the franchise. Kari Jackson discusses the expansion of the franchise in the wake of the Civil War, but at the same time notes that the Fourteenth Amendment came with “a little loophole” that allowed states to withhold the vote from criminals. “And there hasn’t been an explicit voting right” to rectify this, she says. She believes revoking felons’ voting rights is deeply problematic, and just one way in which voter suppression persists.

Impact of Shelby County v. Holder

States retain a great deal of authority to interpret and implement voting rights as they see fit. Lilia Scudamore, the only senior in the group, cites the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder. That landmark decision led to some of the very changes that today are resulting in long lines at polling stations; namely, state and local governments can now make changes to voting laws and practices without federal “preclearance.” Scudamore says this decision essentially “undid the Voting Rights Act” (which outlawed discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after Reconstruction). “The same day that it passed, Texas disenfranchised 600,000 people in one day,” she says, noting that it (Shelby) disproportionately impacted non-White voters.

“It scares me….It’s very unnerving,” says Charlotte Donelson, when she hears Trump supporters on the news saying they won’t respect the election results if Trump loses.

In fact, many of the gains in minorities’ access to the franchise in the years following the 1965 Voting Rights Act were predicated on federal preclearance. The impact was greater representation of non-Whites in Congress and greater voter turnout by non-Whites. Eliminating this requirement led to swift changes in the wake of Shelby v. Holder that negatively impacted voter turnout and reduced polling stations, especially in African-American counties. Five years after the decision, The Atlantic concluded “it’s become clear that the decision has handed the country an era of renewed white racial hegemony.”

Crow understands students’ concerns, and says the House of Representatives has been working to safeguard democracy by enshrining protections through legislation. “We passed the Voting Rights Advancement Act last year in the House to address the Shelby v. Holder decision that really took the teeth out of the 1965 Voting Rights Act…. It reinserts some oversight and important protections for folks throughout the country.” [That 2019 bill passed by the House (228 – 187) was not passed by the Senate and signed into law.] Crow says much of the voter suppression that occurs around the country happens at polling stations. He thinks a lot of the inequities in voting could be short-circuited through the measures Colorado already has in place, including automatic voter registration and mail-in balloting. These measures increase access to voting while limiting the opportunities for voter suppression.

Ben Getches finds it ironic that the Electoral College, which was established to ensure representation, increasingly means “we’re focusing on the six or seven swing states,” which he sees as limiting representation.

Fundamental Changes Needed?

Many of the students advocate for fundamental reforms to suffrage as a solution to what they see as undemocratic practices limiting our democratic institutions. Rashad Brimah believes partisanship is a fundamental problem with our political system today: “People care more about their party than upholding the Constitution.” Ben Getches suggests ranked choice voting as a solution that would foster greater democracy. “The main way to fix this is ranked choice voting,” he says, suggesting that by ranking their candidates in order of preference, voters could show their support for more than the two main parties, making for a more representative system. “Then you could vote outside of partisanship.”

Though some states are using ranked choice voting, Crow says it has had mixed impacts. He suggests that these types of significant changes are premature when we have not exhausted the other options for reform. “I think there’s this instinct to want to jump several steps ahead on where we are, when you know a large number of Americans—millions of Americans actually—struggle just to exercise their fundamental right to vote and to have access to polling stations. I think the focus really has to start there,” Crow says.

Other students lay the blame for our democracy’s limitations at the feet of the Electoral College. Scudamore believes the Electoral College, too often, “is unrepresentative of the popular vote,” a problem that has increased as the U.S. population has grown. Reflecting on the Founding Fathers’ intentions in creating the Electoral College—to ensure smaller states’ representation in the national vote—Charlotte Donelson cites the example of Wyoming, with about half the population of Rhode Island but with almost the same number of electoral votes (Wyoming has 3, Rhode Island 4). “It is pretty outdated….we should get rid of it,” says Donelson.

Lilia Scudamore warns of the dangers of packing the Supreme Court, which would make “the one branch of the U.S. government that is supposed to be the nonpolitical branch possibly the most political.”

“A lot of the states that went red in the last election are states with stricter voter ID laws, so there’s definitely a lot of voter suppression in different states,” says Rashad Brimah.

Lindsay Bader says, “Since the President gets to appoint the Supreme Court justices, people we aren’t electing are deciding what the Constitution means for us.”

![]() While Crow appreciates that “There are population shifts that mean that more of the Senate represents fewer Americans and certainly that’s something that we need to talk about,” he doesn’t wish to “engage in hypotheticals two weeks out from the election of our lifetime.” He supports the present ballot initiative favoring the National Popular Vote, which would affirm Colorado’s participation in this national effort to circumvent the Electoral College. “I think it’s good for the state. I think it would help support the idea that one person equals one vote, and that the will of the people in the popular vote should select the president. I firmly believe that, and it’s about protecting our democracy and protecting the vote.”

While Crow appreciates that “There are population shifts that mean that more of the Senate represents fewer Americans and certainly that’s something that we need to talk about,” he doesn’t wish to “engage in hypotheticals two weeks out from the election of our lifetime.” He supports the present ballot initiative favoring the National Popular Vote, which would affirm Colorado’s participation in this national effort to circumvent the Electoral College. “I think it’s good for the state. I think it would help support the idea that one person equals one vote, and that the will of the people in the popular vote should select the president. I firmly believe that, and it’s about protecting our democracy and protecting the vote.”

U.S. Congressman Jason Crow talks to a constituent during his 2018 election campaign.

Protecting Democracy through Legislation

Whichever candidate one supports for the presidency, it is undeniable that the Trump administration’s unprecedented approach to governing has resulted in some valuable lessons. The things that voters and legislators took for granted because they were “the norms and customs and traditions of our democracy,” says Crow—like providing tax returns to the public—proved elusive at best over the past four years.

As a remedy, in September 2020, the House introduced legislation called the “Protect our Democracy Act.” Crow says it “puts protections in place and codifies things that we have come to terms with in the Trump administration, that need to be put into statute.” According to The Washington Post, “seven committee chairs signaled their legislation is intended to ‘prevent future presidential abuses, restore our checks and balances, strengthen accountability and transparency, and protect our elections.’” The new law would also come with enforcement power, including congressional subpoenas.

As the election nears, Crow says he is concerned about the president’s words that seem to lay the groundwork for a disputed election and the peaceful transition of power, should the president not win reelection. “I’m paying very close attention to that, having a lot of discussion with my congressional colleagues about it, and we’re going to be vigilant and defend our democracy, and defend the vote, and defend the election as we should do and as we have a constitutional obligation to do.”

0 Comments