Fazal Sheikh has spent 28 years traveling the world to photograph displaced and exiled people and document their experiences. His photo exhibit, Common Ground, is at Denver Art Museum.

“I wanted to convey a sense of what refugee life is like—to build understanding, one person at a time.” —Fazal Sheikh

Fazal Sheikh’s portraits convey more than just faces; they tell the stories of people surviving and triumphing over unimaginable hardships. Sheikh’s life work is raising awareness of international human rights issues through his documentary photographs. “My photos reach across boundaries of gender, nationality and religion. I hope to bring change by connecting people across the world,” Sheikh said at a media preview of the exhibition.

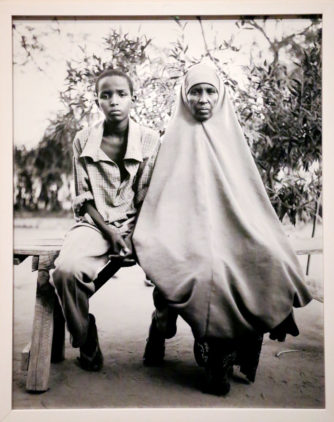

Salado Hassan Aden and her son Ahmed, Somali refugees at the Dagahaley camp in eastern Kenya, from the series A Camel for the Son. An estimated 500,000 people have been killed in Somalia since the start of the civil war in 1991.

Common Ground: Photographs by Fazal Sheikh 1989-2013, at the Denver Art Museum (DAM) through Nov. 12, features more than 170 portraits and landscapes chronicling individuals in displaced and marginalized communities around the world. Their circumstances are mainly the result of war, exploitation and poverty.

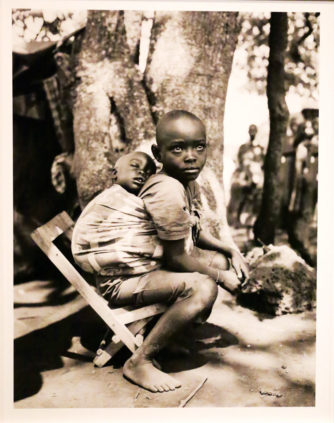

Sheikh’s global travels connect him to refugees living in exile camps in East Africa, Afghanistan, Kenya, Pakistan, India and the Netherlands. His early portraits capture refugees of the African wars in the 1990s, including a portrait of two Borana war widows who walked 600 miles barefoot at night to reach a safe camp. “You can see their resolve and their resilience,” said Eric Paddock, curator of photography at the DAM.

Born in 1965 and raised in New York City, Sheikh is the son of a Kenyan father and an American mother. While attending Princeton in the 1980s, Sheikh visited his father’s native land and was shocked by the victims of war in Africa. “I was ill at ease with the media coverage coming out of this because the people were so generalized,” he said. “I decided to share instead the specific, intimate voices of the people there. I wanted to convey a sense of what refugee life is like—to build understanding, one person at a time.”

Since context is so important to his work, Sheikh spends long periods of time in the places he photographs. He spent three years in various Somali war camps and nearly four years in Afghanistan. “I sit with the people, drink tea, listen and talk with them through an interpreter,” Sheikh said.

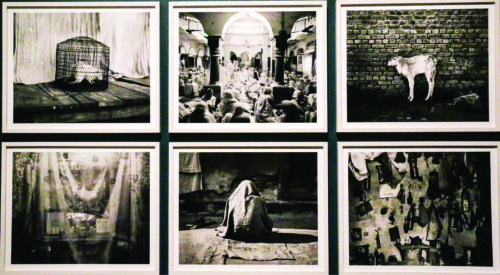

Scenes at an Indian ashram where widows live after they are put out of their homes. “The widows often chant for eight hours at a time,” said Sheikh. From the series Moksha [heaven].

Sheikh documents the stories of the people he meets in a set of publications, the International Human Rights Series. In keeping with his mission to further the understanding of complex human rights issues, the publications’ text and photos are available online free of charge at fazalsheikh.org.

Several of his publications have been brought to the attention of the media and political representatives to confront societal prejudice. His Ramadan Moon book, about a woman exiled from Somalia with her young son and detained in the Netherlands, was brought before the Dutch government. Ultimately, she was allowed to return to Somalia to retrieve her two daughters.

Manjula (portrait above) and other young women flee to shelters to escape draconian practices against women in India. Manjula tells the story of her arranged marriage: “I was 16 and I had no choice in it. After a few years, my in-laws and my husband began to abuse me physically. If we are divorced, my husband will keep the children. After all, they are boys.”

The exhibition features excerpts from refugees’ testimonies, including that of Abshiro Aden Mohammed, the leader of the women’s group in the Dagahaley Somali refugee camp in eastern Kenya: “Often the women who go to gather firewood in the surrounding bush [just outside the camp’s borders] are raped. But we go instead of the men because they are killed. The ability to listen has been lost. The Koran says that women are to be honored and not mistreated. If a person cannot fear and respect Allah, how can he respect a human being?”

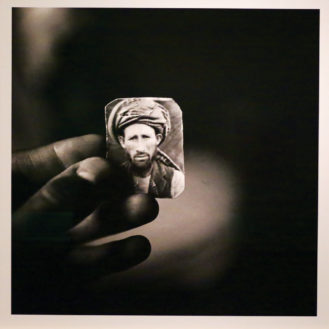

Abdul Aziz holding a photograph of his brother Mula Abdul Hakim, killed while fighting Communists who had taken their home village. Taken at Khairabad Afghan refugee village in North Pakistan, 1997, from the series The Victor Weeps.

In India, Sheikh visited women who had been cast off by their families, including widows who were put out of their homes after their husbands died. The widows live in an ashram in Vrindavan, considered to be the birthplace of Hinduism. “Their stories revealed how powerless some of the women had been under the strictures of traditional Hindu law,” says Sheikh’s website. “They were victims of enforced marriage, physical violence, sexual abuse and neglect. Some had been evicted from the family home once their children were married. But they had formed a sisterhood at the ashram.”

From the sisterhood grew the activist organization Shakti Shalini, formed to help the widows’ daughters escape cruel practices against women. “Dowry death is a practice wherein if a bride’s dowry is insufficient, she might be found ‘accidentally’ burned to death,” said Sheikh. “Domestic violence is rampant, as is the practice of aborting female fetuses or killing girls at birth. Shakti Shalini provides both shelter for women and advocacy to the Indian government to bring gender equality and an end to violence.

A boy carries his brother to the safety of a refugee camp. In 1991 and 1992, refugees from the wars in Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia flooded into camps along the eastern border of Kenya.

“People say I am an activist, but I am just a witness to the real activism that the people themselves undertake.”

Common Ground from Steve Larson on Vimeo.

0 Comments