Colorado’s wildfires are getting worse. There are more of ’em every year. And more Coloradans, too.

When we read statements like these, it’s easy to assume that wildfires are caused by having more people around. But that isn’t always the case because correlation does not equal causation.

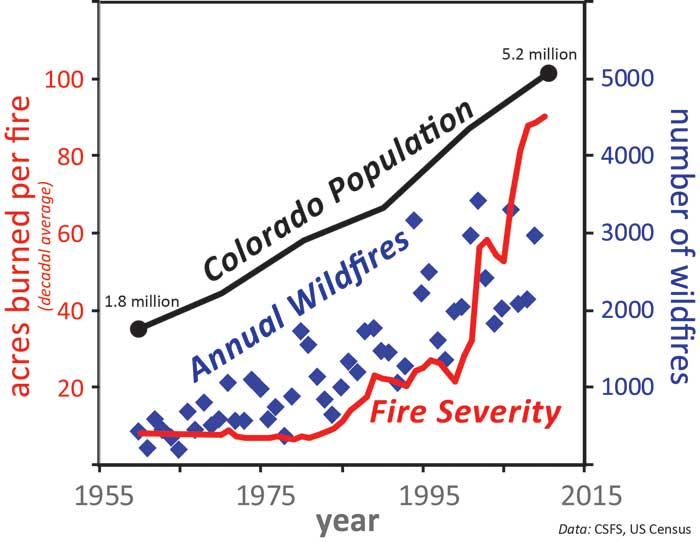

The severity of our wildfires is increasing at the same time our population is growing. But this relationship is only a “correlation”—a type of association where one pattern mirrors another. It makes sense that population size could cause an increase in wildfire severity; more people = worse fires. But this is not true. Rather, the increase in severe fires is caused by a combination of changing weather, forest conditions, forest evolution and historical fire-suppression practices.

Although we often make decisions based on such correlations, we have to be careful not to infer causation from correlation. Just because two things are “linked” or correlated doesn’t mean that one causes the other.

“Causation,” which is when something produces an effect, usually requires identification of a mechanism or dependence. Thus, although the severity of Colorado wildfires is not related to population growth, the frequency of such fires appears to be. More people = more chances for accidents —> causes more wildfires. This is especially true for human-caused wildfires, given that more houses are being built at the interface between urban and wildland areas.

Correlation, causation, or both? Wildfire data is from non-federal Colorado lands, with average wildfire size used as a metric for fire severity.

At other times, cause is harder to identify because it is indirect. For example, pine bark beetles have been ravaging more and more of our forests every year, and this pattern correlates with a pattern of warmer winters. The correlation occurs because fewer beetle larvae are being killed during our normally frigid winters, allowing more of these critters to wreak havoc on forests. But it isn’t the beetles that are causing the biggest increase in conifer tree deaths, it is the nasty “blue stain” fungus they infect trees with, and which symbiotically help them to thrive.

Sometimes correlation does not lead to an understanding of causation, but to other discoveries. For example, French citizens, despite their fatty diets, have relatively low rates of coronary heart disease. After this initial correlation was noted, there was debate about what caused this “French paradox.” Investigations are ongoing, but because red wine was one of the hypothesized causes, dietary effects of alcohols were scrutinized. Surprisingly, results indicated that moderate consumption of alcohol facilitates “good cholesterol” production, which inhibits “bad cholesterol” retention and thus causes less buildup of plaque in arteries. Red wine, in contrast to beer or other spirits, has additional compounds that cause less plaque formation and growth. Unfortunately, although this research triggered a renaissance in both wine drinking and the study of wine compounds, neither completely explains the French paradox.

Correlation can be useful even if we don’t yet understand causation because it can alert us to problems that might occur. For example, Colorado is at the epicenter of a correlation that may have national implications—marijuana availability and kids’ accidental marijuana consumption. Recently reported incidents at Aurora’s Children’s Hospital Colorado mirror national trends in child marijuana exposure, where rates of possible marijuana poisonings have increased by approximately 40 percent in the last two years. These increases are concomitant with widespread rollout of marijuana dispensaries. If this correlation is causal, it predicts that such incidents will become more common with the full-scale legalization of marijuana in Colorado. It also begs questions of causation: Does marijuana availability cause more kids to accidentally ingest it? Or does it merely correlate with increased incidences of accidental marijuana ingestion? For children, a key mechanism for poisoning is eating marijuana-infused food products. Is the cause of these poisonings the product’s packaging, or the children’s curiosity, or negligent parents forgetting to put away the cannabis brownies and THC lollipops?

Colorado is at the leading edge of other similarly contentious issues. For example, will adoption of tighter gun-control laws reduce shootings or make our schools safer? Will loosening restrictions on over-the-counter sales of the morning-after pill lead to increased rates of teen sexual activity? Although we don’t yet know the answers to these questions, identification of correlations and causes for these issues will be amplified well beyond Colorado—in the national debate about how to address them. By understanding the difference between cause and correlation, you can provide an informed voice in such discussions.

James W. Hagadorn, PhD, is a scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Suggestions and comments welcome at jwhagadorn@dmns.org.

0 Comments