Mayor Mike Johnston has held more than 30 town hall meetings across the city to explain his House1000 initiative that is designed to get 1,000 people who are currently living on the streets into temporary shelter by year’s end. He has met some angry resistance from people concerned about potential negative impacts to their neighborhoods.

Despite some pushback at public meetings, Mayor Mike Johnston’s ambitious plan to move 1,000 people currently living on the streets into temporary housing by the end of the year is still on track, according to Cole Chandler, the mayor’s lead advisor on homelessness. “We’re very much pushing forward and think it’s an achievable goal.”

Many people who attended meetings about the Mayor’s plan to establish micro-communities for the homeless said they were concerned about negative impacts on neighborhoods.

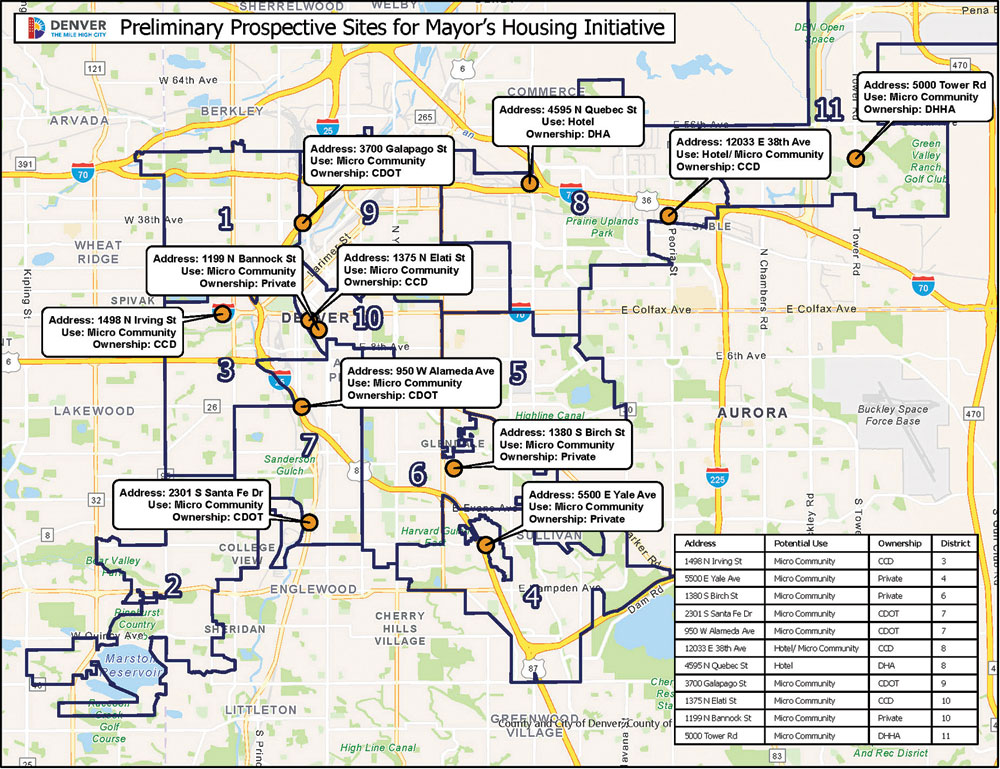

In late August, the city released a map of 11 potential micro-community sites located across the city in an initiative called House1000. Most of the micro-communities will be built on vacant land using tiny homes or pallet shelters, but in Northeast Denver, the micro-communities will be placed in two hotel buildings. They are the former Best Western Hotel located at 4595 N. Quebec Street and the former Stay Inn located at 12033 E. 38th Avenue. These buildings offer 194 units and 96 units, respectively.

The hotel conversions are budgeted at $24 million in the mayor’s 2023 budget and will be paid with federal dollars that the city received as part of the COVID-19 American Rescue Plan Act. Adding together the purchase price of the buildings plus the expected renovations, the cost per unit will be between $100,000 and $150,000, a price that Chandler calls “astronomically low” if you compare it to the market price of condos in Denver.

Since he took office in mid-July, Mayor Johnston has held more than 30 town hall meetings, with at least five more narrowly focused meetings slated for October. At several of the meetings, angry residents spoke out in opposition to the plan citing the high costs, fears that Denver would become a magnet for unhoused people in other parts of the country, and concerns that certain sites are located too close to schools or will cause too much disturbance to residential areas. Johnston has said that he wants feedback and is open to new ideas for locations, but insists that the micro-communities must be spread out across city council districts so that one area of the city isn’t overburdened. “The way you solve this is to deconcentrate poverty. You want to spread people out to get services so no one neighborhood has to carry a disproportionate share. That’s the most successful way to do it and the most fair way,” Johnston explained at a particularly contentious town hall.

Cole Chandler leads the Mayor’s homelessness initiative called House1000.

Chandler says the city is pushing forward with permitting and doing its due-diligence with site design, although he concedes that some sites could still be changed. Each of the micro-communities will include wrap-around services that include mental health and addiction services, employment counseling, and housing navigation. There will not be a sobriety requirement to move in, Johnston explained at a town hall, since other successful housing programs around the country have found that sobriety requirements don’t work. “What they found was you have to get people in and stabilized and get them services to get out of addiction.” Johnston added that doesn’t mean there won’t be rules or accountability in the micro-communities. “City laws still apply. You cannot deal drugs. You cannot commit acts of violence. You cannot assault people.”

Ana Gloom is an activist with Housekeys Action Network Denver, a non-profit that elevates the voices of the unhoused to help shape policy for the city. Gloom, who was homeless on and off for about 10 years, says she has been shocked by the vitriol expressed by some citizens at the town hall meetings. “It’s vile. Suggesting that everyone is a drug addict or that the people in encampments want to live on the streets.” Gloom is disappointed in the Johnston plan because she wishes more attention was being given to long-term housing solutions rather than these temporary micro-communities. “I wish he would stop saying he will house 1,000 people. He’s going to shelter 1,000 people. Pallet houses are not houses,” says Gloom.

Chandler says the first priority is getting people off the streets, but the next step is to get people into permanent housing. “But we also know that we’re facing a housing shortage, so part of the long-term plan that you see reflected in the mayor’s 2024 budget is building 3,000 new units of affordable housing per year.” Chandler envisions that it will take most people 6-12 months to transition from the micro-communities into permanent housing.

Chandler says the first priority is getting people off the streets, but the next step is to get people into permanent housing. “But we also know that we’re facing a housing shortage, so part of the long-term plan that you see reflected in the mayor’s 2024 budget is building 3,000 new units of affordable housing per year.” Chandler envisions that it will take most people 6-12 months to transition from the micro-communities into permanent housing.

Many Denver businesses and members of the faith community have offered to help people make that initial transition from the streets to temporary housing. Rev. Ian Cummins of Montview Boulevard Presbyterian Church has been working with other religious leaders and the City to collect items for a welcome kit, which will include bedding, towels, socks, toiletries, and other small necessities. Montview, where Johnston is a member, has raised $13,000 to buy blankets, towels, and laundry bags for the first 500 people that are expected to move into the micro-communities in November.

Mayor Mike Johnston has fielded numerous questions about the site selection process for the micro-communities that will shelter people currently living on the streets. Johnston says it is important that the communities are located throughout the city.

Cummins says that he understands why some people might at first resist the notion of having the micro-communities located in their neighborhoods. “I feel some of those concerns myself, as a father of two and wanting them to have a safe city to grow up in. At the same time, this [housing initiative] is part of the answer of how we change Denver and make it feel safe.” Cummins hopes that as Denver residents learn more about the plan, they will embrace it. “What’s so valuable about Mike’s approach is that it’s grounded in relationships,” says Cummins. “Instead of seeing the unhoused as a threat or something that we just wish would go away, can we find the compassion to make a turn ourselves and say, ‘How can I help?’”

The city has unveiled 11 potential sites for micro-communities to house 1,000 people who are currently living on the streets. The sites in Northeast Denver would involve converting two former hotels: one located on North Quebec Street and one located on East 38th Avenue. Graphic from www.Denvergov.org

That’s exactly what Chandler hopes will happen too. The next round of community meetings will be focused on creating “Good Neighbor Agreements” to facilitate clear communication about goals, responsibilities, and accountability for both the micro-communities and the neighborhood. The next community meetings about the hotel conversions in Northeast Denver will be held on Oct. 5 from 5:30–6:30pm at the Martin Luther King Jr. Rec Center and Oct. 17 from 5:30–6:30pm at the McGlone Academy. For more information about the Mayor’s House1000 plan, visit denvergov.org.

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments