The majority of Coloradans depend on the prairie—and don’t even know it. It’s much more than a flat carpet of tumbleweed-infested dirt clods—it’s an economic catalyst. Covering about 40 percent of the state, it impacts mountain towns and underlies the Mile-High City.

A prairie is an ecosystem or habitat. Here in Colorado it exists east of the Rocky Mountain foothills, on a rolling landscape that’s part of North America’s Great Plains.

The Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge is trying to recreate a native prairie ecosystem as much as possible in an urban area. Their efforts have included bringing in a herd of bison.

But Colorado’s plains aren’t like those of the Midwest’s Corn Belt. They’re a mile high because when the Rockies rose upward 70 million years ago, they lifted the plains like canvas over a tent pole. Since then, the part of this landscape that underlies most Front Range cities has been dissected by rivers, creating a broad bowl-shaped valley littered with small hills. Called the “Piedmont,” from Italian, meaning “at the foot of the mountain,” this region differs from the flatter terrain to the east, known as the “High Plains” or “Eastern Plains.”

The most direct economic impact of our prairie is on agriculture, a multibillion-dollar industry in eastern Colorado. By understanding how native prairie ecosystems succeeded, we’ve harnessed the soils and unique climate of the plains to grow corn, wheat, hay and sugar beets, and to raise cattle, sheep and poultry. Hemp is a recent addition.

The high elevation of these settings makes it challenging to live or to farm there, because they’re more susceptible to temperature extremes. And, to wind. If you’ve spent time here, you know what I’m talking about. Autumn wind. Winter wind. Spring wind. And of course, the summer winds. A recent drive to Hays, Kansas, provides an example. On a rail-straight, east-west-trending highway, I steered left for five hours heading east, and then steered right during my entire return trip. Wind scoffed at me the whole time. Yowza!

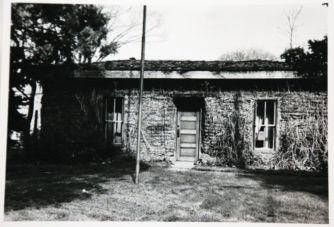

The sod home at the Wheat Ridge historical society was built around 1860 of two-foot chunks of sod. It was covered with plaster for preservation.

Farming the prairie isn’t straightforward, and many failed during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, when a series of droughts, overcultivation and deep plowing caused massive erosion of the topsoil. Collapse of the region’s agricultural community soon followed. Many of these abandoned efforts were purchased by the government and consolidated into the Pawnee and Comanche National Grasslands, where short- and mid-grass prairie and its associated fauna are slowly returning to their natural state.

Fortunately, many of the prairie’s physical and biological components are resilient, and biologists and conservationists are working to protect those that aren’t. The prairie’s anchoring fauna and flora have evolved to repatriate disturbed and new areas, so in some cases they can be successfully reintroduced to plains habitat. Witness the ongoing prairie rehabilitation of Colorado’s most toxic Cold War relics—the Rocky Mountain Arsenal and Rocky Flats.

Surprisingly, the prairie has a strong impact on mountain ecosystems. For example, the prairie is the breeding ground for miller moths. Plentiful supply of these nocturnal pals is pretty important—once hatched, they migrate from the prairie up to mountain meadows, where they pollinate vast numbers of wildflowers, providing a foundation for local food webs. Prairie-born moths are also a yummy and nutritious food source for all sorts of mountain beasts—from tiny bats to hulking bears. To learn more, see https://frontporchne.com/article/moth-madness/.

Mountains also affect the prairie, acting like the lead cyclists who break the wind for riders drafting behind them. In the case of the Rockies, eastward-moving moist air rises over the peaks, loses moisture, and flows past the Front Range and much of eastern Colorado without dumping much precipitation. This “rain shadow” is what keeps the eastern half of Colorado so dry, even in winter.

This photo shows the house with the plaster removed during a renovation project.

The dearth of rainfall means our prairie has few tall grasses or trees. Instead it’s dominated by short- and mid-height grasses. These grasses are drought-, cold-, heat- and grazing-resistant, and can go dormant when conditions are unfavorable. They have amazing root systems to help them survive. In creek bottoms and lowlands where taller counterparts of these grasses lived, early settlers cut the grass’ sod into bale-shaped blocks, using them to construct homes. The root structure of such sod is oodles stronger than that of the turf you see on fields and lawns today. You can visit one of these homes at the Plains Conservation Center or at the Wheat Ridge Historical Society.

Today’s prairie endures as tiny patches on the plains’ quilt of agriculture, urban life, and invasive species. Its humble terrain houses an incredible diversity of plants, animals and scenic vistas. By carefully shepherding its resources and diversity, it can grow, be enjoyed, and support our future.

This is OK with me, Richard. Good luck in Roxy. James

Good information. Thanks. I have been working with a team on discussing homesteads in Roxborough State Park. May I use your information to discuss the eco system of the Park?

Thanks,

Richard

As a courtesy to our writer, James Hagadorn, you should contact him directly at jwhagadorn@dmns.org. He’ll be interested to know where and how you’d like to use this information. Please credit the Front Porch or the Historical Society for the photos.