The state’s first COVID-19 drive-through testing station opened on March 11 in Lowry and was able to test 100-150 people per day with doctor’s orders. After two days, it moved to the Coliseum to better manage logistics; it is now being moved to different locations around the state.

Denver Mayor Michael Hancock’s March 23 “Stay at Home” order underscored the half-hearted response to social isolation. The weekend before this order, Denver parks and playgrounds were crowded again after a thaw in the late March snow. Buy-in for social isolation is understandably challenging for many in a society that cherishes individual freedoms and individualism over the collective. The pandemic highlights how our behavioral norms as well as our nation’s overarching political philosophy may be incompatible with a crisis of this nature. Front Porch interviewed several local experts for their thoughts on the tensions inherent in an individualistic, democratic society curtailing individual freedoms to reduce contagion.

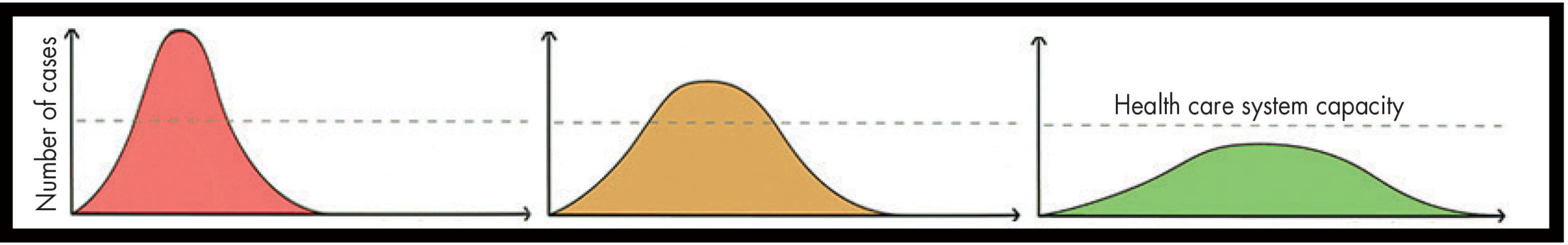

“Flatten the Curve” has suddenly become part of our everyday language—and it’s all about changing people’s behavior so the health care system doesn’t get overwhelmed. “Even if every person on earth comes down with COVID-19, there are real benefits to making sure it doesn’t all happen in the next few weeks,” says the Director of CU’s Public Health Program, Matthew McQueen. In this article, three experts talk about the challenge to accomplish that.Graphic courtesy of Matthew McQueen

Is Our Political System An Obstacle to Fighting a Pandemic or a Strength?

Left: Park Hill resident Dr. Karen Adkins, Professor of Philosophy. Middle: Univ. of Denver Sturm College of Law Professor Govind Persad. Right: Lowry resident and public health ethicist Dr. Daniel Goldberg

Dr. Karen Adkins, a professor of philosophy and Park Hill resident, is in her 24th year of teaching at Regis University. She understands this central conflict in terms of libertarianism, which she describes as the idea that “government should be as small as possible because individual liberty is what defines us, and the more we give over our liberty and our autonomy to governmental limits, the less we become fully human.” Though she appreciates the libertarian philosophy, “big crises tend to reveal their weak spots; big problems can’t really be solved by a concatenation of individuals, because the problems are bigger than you can reliably depend on an assembly of individuals to solve.”

“…romanticizing the WWII era of shared sacrifice omits that “we were able to pull together, in part, because we were demonizing others…we were interning the Japanese and saying ‘they’re dangerous’…and we see some of that now.”—Dr. Karen Adkins

The Founding Fathers valued individual liberties, Adkins says, but the government they established was mixed; because “they lived in small towns, they were deeply interdependent.” Though some of that sense of interdependence has been lost in the modern U.S., the pandemic reveals how very interdependent we remain at a global level.

For Dr. Govind Persad, a professor at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law whose work centers on the confluence of healthcare and law, the pandemic suggests the strengths of our federalist system: “There’s no expectation that everybody needs to listen to one authority…even if the response at the federal level has not been what it could have been, a lot of states have stepped up in creative ways to think about strategies to slow the progress of the pandemic.”

As families fill their time together with activities at home, the language we all now associate with COVID-19, “flatten the curve,” has entered the lexicon of sidewalk graffiti.

Persad extolls individualism insofar as it continues to inspire novel approaches to the novel coronavirus: “You’re seeing scientific labs and other groups thinking innovatively about different strategies for addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and I think that’s something that’s really exciting to see.”

“We better all start pulling in the same direction if we want to leave our houses in the next 12 months, because otherwise the only hard stop to all of this is sufficient herd immunity, which would require a huge amount of morbidity and mortality to get to.” —Dr. Daniel Goldberg

But, as we watch New York battling the first and most intense wave of COVID-19 in this country, giving us a glimpse of what scientists tell us will happen elsewhere, it seems clear that viruses do not respect state and local borders. Therefore, any response that is not cohesive and comprehensive will ultimately be insufficient to exorcise COVID-19.

The state’s first drive-through COVID-19 testing site in Lowry created logistical and safety problems due to the long lines. It was quickly moved to the Coliseum.

When asked about enforcing social isolation in a society that cherishes individual freedoms, Lowry resident Dr. Daniel Goldberg, who specializes in public health and serves on the faculty of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, says, “There’s no question that more collectivist societies do this better,” referencing Singapore and South Korea as examples. Goldberg also cites the more robust social welfare systems and safety nets elsewhere, and says, “There’s no question that some of what the U.S. is experiencing now and some of the trouble everybody sort of thinks we’re in for…is almost certainly a function of the fact that we don’t have much of a social safety net.” This fact, Goldberg believes, coupled with decades of underfunding public health despite credible predictions of a pandemic, have put us where we are today.

“We’re faced with an ethical dilemma here, which is two potentially catastrophic outcomes. The one is letting coronavirus run like fire through our populations. That’s no good, obviously. But the other is the public health catastrophe of asking people to practice extreme physical distancing for 12 months.” —Dr. Daniel Goldberg

If we hope to leave our homes in the coming year, Goldberg says we need “massive, community-based public health surveillance testing.” He stresses that this is not point-of-care testing but community-based testing that would allow experts to “identify exposures, epicenters, and hotspots.” This sort of data will allow for “targeted mitigation” rather than the current blanket mitigation requiring everyone to stay at home. The alternative, barring a vaccine which is at least a year away, is to achieve “sufficient herd immunity, which would require a huge amount of morbidity and mortality to get to,” says Goldberg.

On March 23, Mayor Hancock strengthened Denver’s restrictions to stop the spread of COVID-19. All non-essential businesses were ordered closed and a Stay-at-Home order went into effect at 5pm March 24. A copy of the order, with the list of excepted businesses is posted at frontporchne.com/article/governor-mayor-heighten-restrictions/

The day before, Gov. Polis made a plea to all Colorado residents to strictly abide by social distancing, and recommended that people in their 70s and 80s and those with medical conditions not leave their homes.

The Costs of Social Distancing

The closure of DPS schools and Denver City rec centers and libraries on March 16 was just the beginning of the closings ultimately needed to prevent a spike in COVID-19 cases. Restaurants and bars were ordered to close the next day, except for carry out service.

Social distancing and other restrictions come at a cost to individual freedoms. “Every day that we’re doing this extreme physical distancing from each other we are imposing harms, and I certainly think that they’re justified at the present, but the longer it goes on, in my view, the more the ethical justification for it has to be questioned—and the legal justifications— because as a public health lawyer, we can’t ask a country of 300 million people to engage in extreme physical distancing from each other for 12 months. It’s not reasonable. It’s not possible. We’re faced with an ethical dilemma here, which is two potentially catastrophic outcomes,” says Goldberg. “The one is letting coronavirus run like fire through our populations. That’s no good, obviously. But the other is the public health catastrophe of asking people to practice extreme physical distancing for 12 months.” One of the best predictors of mortality among older adults is social isolation, and he and other public health experts worry that social distancing may result in further casualties.

Persad likewise emphasizes the importance of “really carefully tailoring any rules that you put in place in a way that tries to maximize the good that they do versus the burden that they cause.” He stresses the importance of using data from other places to craft flexible approaches, designing measures that yield equivalent benefits while mitigating some of the costs. If the burdens on individuals are too onerous, he worries that people may “break down,” and say “I can’t do this anymore. I’m going to stop [e.g. social distancing].” He suggests metering access to stores or public facilities as a way of mitigating the burdens.

With restaurants and bars closed, the Stanley Marketplace interior may be empty, but multiple restaurants there are offering curbside pickup in the parking lot. Numerous East Metro/Stapleton/Northfield/Lowry carry out options can also be found at ToGoDenver.com.

The day before Mayor Hancock’s order to stay at home, Gov. Polis made a plea to all Colorado residents to strictly abide by social distancing, and recommended that people in their 70s and 80s and those with medical conditions not leave their homes.

Though some have likened the current emphasis on self-sacrifice to the homefront during World War II, Adkins cautions that our romanticizing of this era often forgets that “we were able to pull together in part because we were demonizing others…we were interning the Japanese and saying ‘they’re dangerous’…and we see some of that now.”

Will the Pandemic Cause Changes in Public Health Policy in the U.S.?

“We actually need to be much more serious about public health and how we approach health care in this country, and I don’t have a ton of confidence that people will be ready for that kind of national conversation when the crisis is over,” says Adkins. She reflects on our tendency towards episodic unity in the wake of severe weather events like Hurricane Katrina’s devastation: “The frequency and severity of catastrophic weather events has not really prodded a broad discussion of climate change and its impacts and how we should be funding a whole host of initiatives.”

Students these days might be found at the kitchen counter, the coffee table, the computer—but not at their desks at school.

If we reflect on the words of the Declaration of Independence, there is no tension between individual liberties and the current restrictions imposed for the common good, suggests Adkins. “Life, liberty, and then the pursuit of happiness…life comes before liberty. They are clearly ranked,” she says. As Governor Jared Polis recently stated, if we are unwilling to relinquish some of our individual freedoms during the pandemic, inadequate resources—hospital beds, face masks, and respirators—will force nurses and doctors to make even tougher moral choices, leaving the Grim Reaper to exercise his authority.

For more information: https://www.childrenscolorado.org/conditions-and-advice/parenting/parenting-articles/how-to-talk-to-kids-about-tragic-events/

Great article! Quick comment, the populace certainly is rightfully concerned about loss of freedoms that are inherent in our constitution. “.. Life, liberty, AND the pursuit of happiness” – there is no “then.” Not a ranked issue but equal. Just like a recipe, order does not denote rank. Such a strange time..

Thanks for your comment, and for reading! Actually, recipes do rank ingredients in order of their use in the recipe, so that may not be the best comparison to make your point. I’m a historian by training and always thought they were ranked, too, but I think we’d need a Jefferson scholar to weigh in on this question to be certain.