Dr. Stefanie Huff counsels a new patient by explaining how buprenorphine works using a model. Buprenorphine is the active agent in Suboxone, which Briar Rose prescribes to patients trying to stop using heroin or other opiates.

The opioid addiction epidemic gripping the country has dominated the national news cycle in recent years. Every day seems to bring a new story: the Florida infants strapped into a car seats as their mothers overdose in the front seat; the school nurses trained to administer Narcan in rural towns beset by the epidemic; the cycle of hope and failure as addicts depicted in a New York Times story struggle to maintain sobriety.

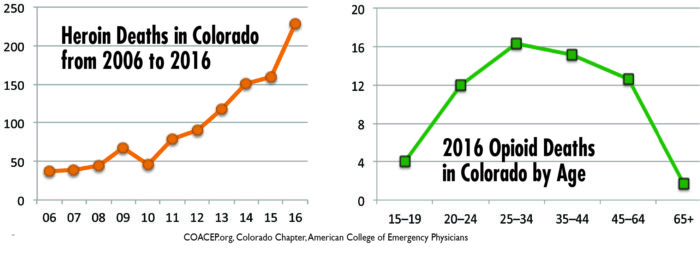

Although Colorado ranked 33rd in the nation in 2016 for its rate of total drug-overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that rate has been steadily rising, with a record of 228 heroin overdose deaths reported in 2016, up from 160 the year before, and 300 dying from opioid overdoses.

And it is not only a rural problem in Colorado— according to reporting by Westword, heroin deaths in Denver are up a whopping 933 percent over 14 years, with an estimated 31 deaths in 2016. The Denver Library, an informal haven for addicts, now carries Narcan and has saved nearly a dozen lives.

Robert Valuck, a professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of Colorado, says there is an 85 to 90 percent treatment gap for opioid addiction, meaning “85 or 90 people out of 100 that have an opioid use disorder and are seeking treatment can’t get it,” he said. For reference, this compares to a treatment gap rate of one to two percent in diseases like cancer. Substance abuse has “among the worst treatment gaps that there are,” said Valuck.

Medication Assisted Treatment

Erika Hurt, 26, sits in her car with her baby in the back seat in the Town of Hope, Indiana. Police said she appeared unresponsive from an overdose and had a syringe in her hand. Medics revived her with a shot of Narcan. She has been clean for over a year and is looking forward to the future with her child.

Photo courtesy of Town of Hope Police Department

As local and state government agencies grapple with the epidemic, private entities are also stepping up. Almost a year ago, Stapleton resident Dr. Stefanie Huff partnered with Dr. Matthew Ponder to open the Briar Rose Medical Group, a medication assisted treatment (MAT) clinic in Aurora. MAT involves the use of methadone or buprenorophine, usually in conjunction with counseling, to help addicts stop using heroin or other strong opioids.

Huff and Ponder have been longtime emergency medicine physicians in the Denver metro area. “We’ve seen the really bad side of things. We’ve seen overdoses that don’t come back. We’ve seen the ones that we saved [come back to the ER],” said Huff. Both had felt frustrated by the repeat visitors, frustrated that there was no effective treatment to offer them, until recently, when a drug called Suboxone became more widely used in the U.S.

Suboxone treatment for opioid is relatively new, gaining traction only in the last five or ten years, and “there is research to show that medication assisted treatment is the best treatment for opioid addiction,” said Ponder. Valuck agrees, “Medication assisted treatment has been shown to be the most effective form of treatment for opioid use disorder, so I strongly support it.”

Suboxone combines buprenorphine and naloxone and is administered under the tongue in film or pill form. Buprenorphine is the active component in the medication. It binds to the same part of the opioid receptor as heroin and other opiates. However, the way that buprenorphine binds is different so it does not give a euphoria like heroin, but diminishes the intense cravings and withdrawal symptoms that addicts suffer when they do not have opiates in their system.

Dr. Matthew Ponder (left) and Dr. Stefanie Huff (right) explain how buprenorphine, the active ingredient in Suboxone, binds to the same part of the opioid receptor in the brain as heroin and other opiates. It lessens withdrawal symptoms that addicts suffer when they stop using.

The naloxone part of Suboxone is an opioid antagonist, or reversal agent, and acts as a contaminant to deter against misuse of the Suboxone. “If a patient takes their Suboxone film and tries to melt it down or shoot it up, the naloxone in it deactivates it,” explained Ponder.

The challenge for providers like Huff and Ponder is convincing other people that Suboxone is a viable option, and not just swapping one addiction for another. Even within the addiction community, there’s disagreement, with some former addicts and counselors believing that since they made it through without medications, others can also.

Ponder and Huff persist, however, offering their outpatient clients Suboxone paired with addiction counseling. “The goal is to get them off Suboxone, but it’s not always possible,” said Huff. She compares it to blood pressure medication—patients can change their diet and exercise but still might need extra help from a medication to maintain their health. One of their patients needs just a milligram a day of Suboxone to maintain sobriety, for example, but her last attempt to go without it entirely ended in a relapse to heroin.

Unlike methadone, which requires patients to go to clinics daily for treatment, Suboxone can be prescribed monthly, allowing addicts to carry on with their lives. Many successfully hold jobs, raise families or go to school.

A typical monthly prescription costs $500, and Briar Rose offers clients a reasonable self-pay option, although most use Medicaid and some use Medicare. Briar Rose hopes to begin accepting private insurance once Ponder and Huff complete their board certifications in addiction medicine in the fall.

Huff and Ponder have been self-funding the clinic because they are so passionate about helping addicts get effective treatment. Reflecting on the national dialogue, Ponder says, “There’s a lot of talk, but it doesn’t seem like the help is there for the individuals who need it.” With politicians and the government mired in debate, Huff and Ponder hope that private outpatient clinics like Briar Rose can fill the gap to reach people who are ready to change.

0 Comments