Denver dignitaries lead a crowd of nearly 30,000 people at the 2015 Martin Luther King “Marade” on January 19 in City Park. Improving police-community relationships was one of the issues addressed.

Left to right:

Albus Brooks, City Councilman, District 8

Anthony Grimes, Pastor

Stephanie O’Malley, Executive Director of Safety

Robert White, Chief of Denver Police

Angela Williams, State Representative, District 7

Elias Diggins, Interim Sheriff

Michael Bennet, U.S. Senator

Michael B. Hancock, Denver Mayor

John Hickenlooper, Governor, and his son Teddy

Wellington Webb, former Denver Mayor

Corey Gardner, U.S. Senator

Far right, unidentified

The death of unarmed 18-year-old African-American Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. and the decision not to indict white officer Darren Wilson, who shot him, has captured national attention. While the exact details of the interaction and subsequent events remain unclear, it is very clear the American public is reacting.

The event brings to light a national concern that black lives matter less. Renewed conversations about racial disparities occupy city forums, neighborhood meetings, and family dinner tables.

In Denver, 30,000 people gathered on January 19 at City Park for the Martin Luther King “Marade,” one of the largest turnouts in the city’s history. Many wore shirts that read “Black Lives Matter.”

While Denver has not experienced an event like Ferguson, the event sends a forlorn message to the African-American community of what can happen to their young men. In a roundtable discussion about race relations, Mayor Michael Hancock said he prays for his son every day.

State Representative of District 7, Angela Williams knows her son has been racially profiled several times. Williams is pushing for police reform that includes better training and strengthening the current racial profiling law.

“Tensions between police officers and minorities are a timeless tale,” says Assistant State Historian Erin Cole. Incidents in which black men are killed by white officers, whether it is right or wrong, continually fuel distrust of the Anglo establishment, which law enforcement traditionally has been, she explains.

In the 60s and 70s in Denver, there were protests against police brutality, not much different than the recent protests surrounding deaths of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, according to Cole.

Officers today are well trained on what they can and cannot legally do. They almost never break the law but may push the limits of their power, according to Denver Police Chief Robert White.

“Part of my job as the chief—part of my job in policing altogether—is to really raise the bar and officers’ consciousness and say, before you make some of these decisions that are impacting people in a negative way, you need to ask yourself, is it really necessary?”

An elementary example is a senior citizen who parks on a street to go to Sunday service. She and an officer across the parking lot wave to each other as she walks inside. After service, she returns to her car to find a ticket for parking too close to the intersection. While she was at fault, was this necessary?

White says no. The senior citizen may tell her friends about the experience and be less inclined to call the police in the future—two strikes against the police. While continuing to educate about the law, White wants young cops to understand the culture he is trying to create at the Denver Police Department. He has taken the opportunity presented by Ferguson to look honestly at the department’s relationship with the community and its perception of racial profiling.

“There are no guarantees that there can’t be a Ferguson in any city in America. What I think we can do is minimize the chances of that occurring and we’ve done that by the philosophy of understanding the police and community are one,” White says.

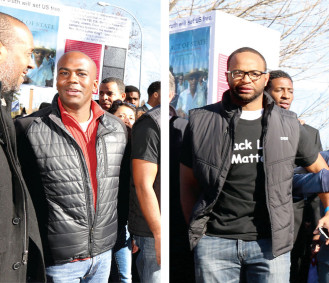

Interim Sheriff Elias Diggins (far left), Denver Police Chief Robert White (middle) and District 7 State Representative Angela Williams (right) take their places at the beginning of the Martin Luther King “Marade” on January 19 at City Park.

He calls policing the trust business; winning the community’s trust is key to their success. Trust begins with exposure. During his three years as chief, he has focused on getting officers involved in the community. Denver officers work the same hours in the same areas each day and are required to know a complete profile of where they patrol, such as businesses and churches.

District 11 City Councilman Chris Herndon says officers in his district are proactive community members.

There has been a lot of national talk whether officers need to reflect the community they patrol. Should a black community have all black officers? Should a Latino community have all Latino officers? “It’s not practical, nor do I think it’s right,” White says. “To say that you have officers in a neighborhood who have an appreciation for the challenges, respect and understanding of the culture of that neighborhood, now that would be accurate. That’s not necessarily determined by the color of an officer’s skin.”

District 511 Lieutenant Robert Wyckoff, who is white, previously worked in District 2 where he was regularly around gang members. He focused on finding similarities with the gang members—both have families, spend their time in the same community, celebrate the same holidays. Going into a community that doesn’t know or trust an officer makes it a lot more difficult, he says. “If you’re uncooperative with me, I’m still going to give you the benefit of the doubt and say ‘OK, you’re going to go to jail and I know you don’t want to wear the handcuffs, but I’m going to talk you into them right now.”

District 511 Lieutenant Robert Wyckoff, who is white, previously worked in District 2 where he was regularly around gang members. He focused on finding similarities with the gang members—both have families, spend their time in the same community, celebrate the same holidays. Going into a community that doesn’t know or trust an officer makes it a lot more difficult, he says. “If you’re uncooperative with me, I’m still going to give you the benefit of the doubt and say ‘OK, you’re going to go to jail and I know you don’t want to wear the handcuffs, but I’m going to talk you into them right now.”

Participants began at the MLK statue in City Park and marched to the State Capitol.

The trust goes both ways, though. If officers don’t trust their communities, they may act out of fear, which can be interpreted as racism, according to Dr. John Nicoletti, a national expert in Police and Public Safety Psychology. He has worked with the Denver Police Department since 1976 and been a part of several high profile investigations, including the Columbine High School and the Virginia Tech shootings.

Nicoletti says people don’t think of cops as humans who make mistakes. “They have families too, and they can get nervous,” Nicoletti says, citing the volume of threats against Denver officers since Ferguson.

Often, encounters between an officer and a citizen are fused with adrenaline. One is in control and the other is “being punished,” according to Steve Charbonneau, executive director of Find Solutions.

Find Solutions is a private mediation company that contracts with police departments in Denver, Boulder, and Douglas counties, as well as Aurora and Colorado Springs. They receive the majority of citizen complaints filed to the Department of Internal Affairs, including discourteous, unprofessional, failure-to-communicate, and racial profiling complaints. They average 200 complaints a year. Denver is one of few U.S. cities that use a mediation service for complaints against officers.

The officer and citizen meet with a professional mediator and discuss what happened and how each party felt. After removing the adrenaline of the initial encounter, officers and citizens are able to discuss the incident civilly and see the other side. Officers learn how they’re being perceived from the racial profiling perspective and the community member learns there is a lot more involved than their race or gender.

City Councilmen Chris Herndon, District 11, (left) and Albus Brooks, District 8, (right) attended the MLK “Marade” in City Park. Like many in the crowd, Brooks wore a “Black Lives Matter” T-shirt, as part of the movement that began after the grand jury declined to indict Ferguson, Mo. officer for shooting and killing unarmed African-African teenager Michael Brown.

“Whether you’re the officer or the community member, those [complaints] are largely based upon perception by either of the parties and so it’s most helpful for people to sit down and talk about that,” Charbonneau says. Officers are significantly less likely to have complaints against them for the same reason after doing mediation.

To hold officers accountable and provide better evidence in situations like that in Ferguson, the Denver Police Department is currently seeking funds to purchase body cameras. Some research suggests body cameras decrease the number of complaints against officers and decrease the use of force by officers.

When officers do make mistakes, they need to have the courage to admit it, according to Lieutenant Wyckoff. “We need to get out in front of the story before it takes on a life of its own. So many “negative” stories can be prevented by courageous leaders who admit to the mistakes we sometimes make. The overwhelming majority of contact our Denver officers have with the public is positive in nature, but if we screw up, we admit to it, involve the community by listening and understanding, correct the problem through discipline and training, and we move forward.”

This article ends with this quote “When officers do make mistakes, they need to have the courage to admit it,” according to Lt. Wyckoff. Huh? In my 25+ years of challenging police brutality, I have never once heard a cop admit he made a mistake. Obviously the shooters/abusers of Landau, Booker, Ronquillo, Kindall, Hernandez and others made huge mistakes but they are never going to admit it. Why do police officers continue to protect the bad apples? That benefits no one. Not the good cops. Not the victims. And certainly not the community.