Mark Shaker (second from left) and dignified stakeholders smile at the opening of an obstetric hospital in Niger built to treat fistulas, a hole caused by tissue damage from a prolonged obstructed labor.

Many know Stapleton resident Mark Shaker as the man behind Stanley Marketplace, a massive project at 25th and Dayton that will transform an abandoned military aircraft ejection seat manufacturing plant into a citywide marketplace.

But few know Shaker as the man behind the success of the Worldwide Fistula Fund. “People call me a real estate developer, but I’m not really. I’m a social worker. I look at things differently to find creative solutions and engage stakeholders,” he says.

So what exactly is the Worldwide Fistula Fund? The story begins in 1995 when Dr. Lewis Wall, an OB-GYN from Washington University in St. Louis, started the organization. He had traveled back and forth to Niger in western Africa for several years performing fistula surgeries.

As part of Shaker’s work to eliminate fistulas, he began a prevention program that trained one woman and one man from each village to educate other villagers how to prevent fistulas. He created an illustrated flipchart, shown here, because many villagers were illiterate.

A fistula is a hole caused by tissue damage from constant pressure on the vaginal area during a prolonged obstructed labor. A hole can be created either between the vagina and bladder or vagina and rectum. Fistulas generally do not cause severe pain, but women can be uncomfortable and get secondary infections. The hole causes leaking, and, due to the smell, women are ostracized from society much like lepers.

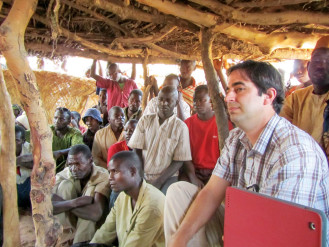

Shaker sits with villagers at an educational meeting about how to prevent fistulas.

Fistulas do not exist anywhere in the world with modern medicine, but are common in impoverished areas. Niger has the highest fertility and poverty rates in the world. Many women have prolonged obstructed labor due to lack of health care or lack of access to a hospital during labor. On top of that, malnutrition and child marriage make delivering a baby much more problematic.

In 2009, Shaker, who was getting his executive master of business administration degree at the University of Denver, read an article in The New York Times about Dr. Lewis Wall and his work to raise awareness and funds for women with fistulas.

Much like Wall, Shaker could not believe this segment of human life existed. “It was absolutely horrific. It was mind-blowing, like how can this exist? How did I not know about this?”

Shaker and three others, including Megan Von Wald who is now a partner in the Stanley project, reached out to Wall and provided pro bono consulting work for six months. Then, the board of directors asked Shaker to be the CEO to help take the organization to the next level. He agreed, and soon after, Shaker flew to Niger to set up the groundwork to build a freestanding obstetric hospital.

After arriving in Niger, Shaker quickly realized it was not the right time to build a hospital. No relationships had been established between the Niger people and the organization. The hospital is located on Christian missionary property in a 99 percent Muslim country with complicated tribal politics. Each group had different priorities and kept to themselves; many hadn’t even met one another despite being neighbors. Shaker needed time to understand the stakeholders, bring them together, and grow support for the hospital before launching into construction.

“There are typically people who come in to these West African countries and stay a few weeks but don’t have continued communication or relationships,” he says, and often make cultural faux pas.

They delayed the project and for six months Shaker had no agenda except to get to know the people.

He carefully navigated the web of stakeholders, including the tribal chiefs, government leaders, the Ministry of Health, the women and families affected by fistulas, and more. After a while, Shaker learned the culture and how to approach each stakeholder. He flew back and forth from the U.S., and each time he arrived, though weathered and exhausted, made sure to go straight to the chiefs and let them know he was in town and looked forward to working together. He went from being totally ignored by the people to being known as “Sugarba,” or “Boss” in the native Hausa language. Village people fought over who got to host him for dinner when he was in town.

Everyone experiences some degree of sorrow or trauma in Niger, according to Shaker, so he wanted to create a reason for the people to celebrate—every time Sugarba was in town there was a dance party.

People began to take pride in the hospital by being involved in the project. Shaker gave villagers responsibilities that were essential to the project’s development. “These people were always told what to do in their lives. They were never a part of a process before. By being a part of the project, they were contributing to the development in a meaningful way and actually wanted to help build the hospital.”

He also created a fistula prevention education program called “When the Sun Sets Twice” that teaches if a woman is in labor for two sunsets, she needs to get to a hospital to prevent a fistula. Because 85 percent of the women are illiterate, he created a flipchart with educational drawings and traveled to all the villages within 100 miles of the hospital. He went over the importance of getting to a doctor quickly, and came up with an evacuation strategy with each group of women. He demonstrated riding in a donkey cart to the next village where there was a car to drive to the hospital. As part of the prevention program, one man and one woman in each village were trained to be educators, which was seen as a great honor.

Within one year of the hospital opening, new cases of fistulas were completely eliminated. The hospital is a model prevention program for similar fistula prevention initiatives around the world. Over time, the hospital operated efficiently enough that Shaker’s role became obsolete and he returned to the U.S. full time, where he started the Stanley Marketplace project.

Located on the boundary between Stapleton and Aurora, Stanley Marketplace has its own web of stakeholders. Much like in Niger, Shaker has sought out the chiefs in Aurora and Stapleton and figured out how to approach them. He has also demystified people’s perceptions of the building, which was locked off and abandoned for many years.

“The concept of really understanding all the stakeholders and meaningfully engaging with them is exactly the same with Stanley as in Niger,” he says.

Inspired by the African markets where people go for the entire day, Shaker wants Stanley Marketplace to be a gathering place for people across the city to come celebrate and spend their day. Much like the hospital that gave new life to Niger, he hopes Stanley will give new life to Northwest Aurora. “So no, I would not call myself a real estate developer. I’m a social worker,” he says.

0 Comments