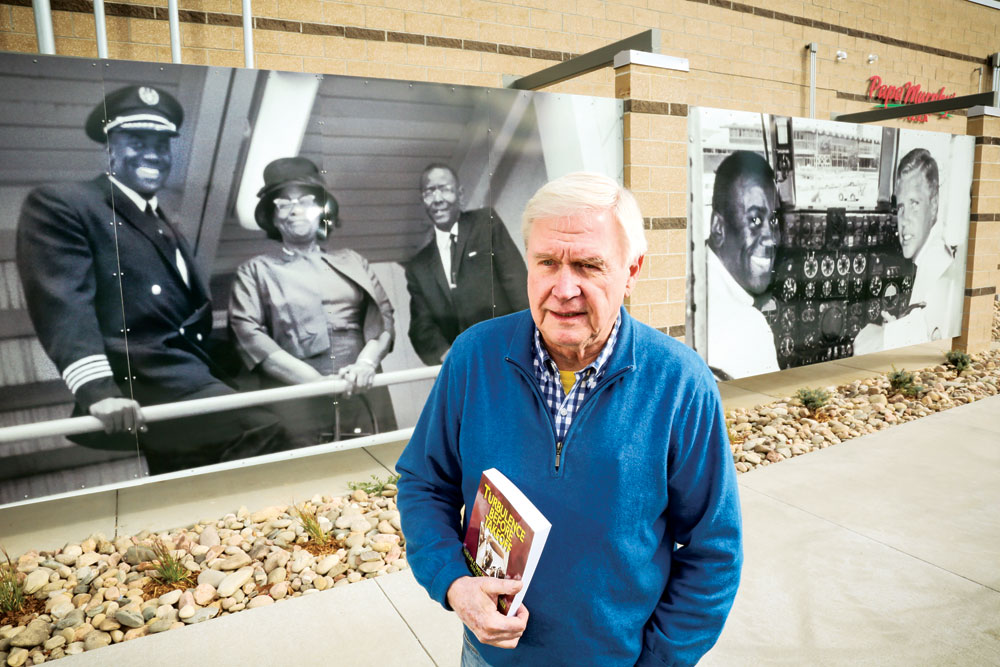

Marlon Green biographer Flint Whitlock holds his book at the site of the Marlon Green graphic screens in the Eastbridge Town Center just west of MLK and Havana.

Pilot Marlon Green broke racial barriers when he won a Supreme Court case banning racial discrimination in airline hiring practices. Green started his career with Continental Airlines at Stapleton International Airport in 1965. Now, two large graphic screens bearing his image have been installed at the new Eastbridge retail development in Stapleton. Green was inducted into the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame in October.

Although far from a household name like Jackie Robinson, Marlon Green was similarly pioneering in breaking through racial barriers. Local author Flint Whitlock chronicled Green’s inspiring history in his 2009 book, Turbulence Before Takeoff: The Life and Times of Aviation Pioneer Marlon Dewitt Green. Racism impacted virtually every stage of Green’s life, and yet he persisted, becoming one of the first black commercial airline pilots in the country.

Marlon Green began his aviation career in the Air Force, where he earned his pilot’s wings and became a commissioned officer.

Stapleton United Neighbors’ president, Amanda Allshouse, was influential in bringing Green’s story to life through these graphic screens. Allshouse had come across Green’s story while researching local history, she said, and brought it to the attention of Evergreen Development, who then worked directly with Marlon Green’s daughter to procure the photographs. Evergreen is installing a commemorative plaque next to the graphics to give an overview of Green’s remarkable story.

Early Life and Air Force Career

According to Whitlock, Green, who was born in Arkansas in 1929, was always a high achiever. His academic prowess in high school earned him a scholarship to Xavier University Prep School in New Orleans, where he was co-valedictorian. After a brief stint in seminary, which was cut short under circumstances that appeared to have racist overtones, Green decided to join the Air Force in 1947, which was still segregated at that time.

Green began in the maintenance unit but developed a keen interest in flying and quickly moved up the ranks in the Air Force. He was one of very few black cadets at the flight school in Randolph, Texas, where he earned his wings and officer commission, specializing in multi-engine aircraft.

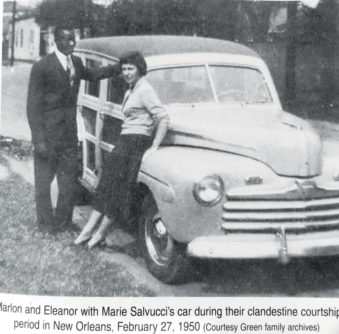

During this period, Green began corresponding with, and later proposed to, a white teacher from Xavier University named Eleanor Gallagher. “She was from Boston, from a very, let’s say, prejudiced family,” recounted Whitlock. “When they heard that she was going to marry a black man, her father said, ‘You’re throwing your life away. I never want to talk to or see you again.’” Unable to get married in Louisiana where Green was to be stationed, the couple tied the knot in Los Angeles in December 1951. Once married to a white woman, however, Green wasn’t allowed to live in Louisiana due to the laws against mixed-race marriages, so he was reassigned to the Strategic Air Command (SAC) base, Lockbourne, in Columbus, Ohio.

Green experienced racism throughout his life, and certainly during his tenure in the Air Force. “General Le May refused to shake his hand in a receiving line, barbers on base wouldn’t cut his hair, and he had his promotion from second lieutenant to first lieutenant held up for about six months because one day he was written up for wearing a pair of nonregulation mittens,” recounted Whitlock. But nonetheless, in the Air Force, Green flew planes and earned regular wages.

Applying for Commercial Pilot Jobs

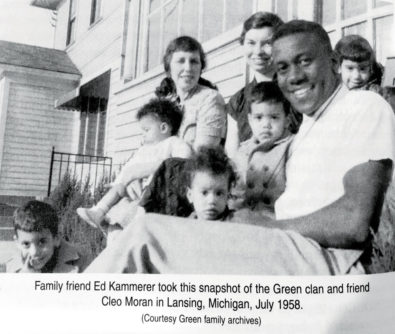

While stationed in Japan, Green read in Time magazine that U.S. domestic airlines were moving away from discriminatory policies that had kept black pilots from flying. With a growing family that would ultimately include six kids, Green resigned his Air Force commission in 1957 and moved back to the States, where he began applying for jobs with commercial airliners and other corporations that needed pilots.

Green courted future wife Eleanor Gallagher, pictured here in 1950, clandestinely.

With over 3,000 hours of flight time, Green was more than qualified, but hundreds of his applications were uniformly rejected. “He got everybody he could think of—senators, congressmen—to write letters of support for him, but still nothing,” said Whitlock.

“Even if your qualifications were 100 percent perfect, we wouldn’t hire you because you’re black,” Green was told by the vice president of United Airlines, according to Whitlock. Whitlock said the airlines were afraid that white customers would refuse to fly if they found out the pilot was black. And, in a country that still adhered to Jim Crow laws of segregation, finding separate hotel and restaurant accommodations for a mixed crew presented logistical problems, especially in the South.

Job applications to commercial airlines required applicants to check off a box designating their race and include a photograph. After rejections from major airlines back East, Green sent in an application to a smaller, regional carrier, Denver-based Continental Airlines, without checking off the race box or enclosing a picture.

In 1957, Green got an interview with Continental and tested in Denver with a group of white pilots. He knew from talking with them he had better qualifications, but in the end Continental hired every other applicant except Green. According to Whitlock, this event was what gave Green “rocks in the jaws”—a feeling of anger so intense that Green finally turned to the law for recourse.

“Rocks in His Jaws”

In August 1957, Green filed a complaint with the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission which ruled Continental had to admit him. Continental refused and took the case to Denver District court, arguing they were not subject to the Anti-Discrimination Commission since they were involved in interstate commerce. The case was ultimately dismissed. To support his family, Green started working menial jobs and became increasingly destitute and desperate.

Through connections at a Catholic church Green attended in Denver, he found attorney T. Raber Taylor to represent him. Green’s suit continued through the Colorado Supreme Court, which ruled against him in 1962, after years of back and forth that laid waste to Green’s finances. Taylor and Green decided to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, and many supporters helped, including Robert F. Kennedy, who filed an amicus brief.

The Greens, shown here in 1958 with family friend Cleo Moran, had six children together. Photos from Turbulence Before Takeoff: The Life and Times of Marlon Dewitt Green by Flint Whitlock.

The court heard the case in March 1963, and a month later came back with “a unanimous verdict in Marlon’s favor,” said Whitlock. “They said that Continental discriminated against him because of racial animus.”

After working out details related to seniority, in 1965, Continental finally hired Green, who flew out of Stapleton International Airport at the beginning of his 14-year career with the airline. While he was not the first black pilot—another man, David Harris, began flying with American Airlines in 1964—it was because of his persistence that the industry opened its doors to people of color.

Green’s successful case resulted in the establishment of the Organization of Black Airline Pilots (OBAP) and helped open up employment for black women to work as part of the cabin crews in commercial airlines. “His victory was really a signature event in airline history and race relation history. It wasn’t just him getting a job as a pilot,” noted Whitlock.

To read more, see Flint Whitlock’s Turbulence Before Takeoff (2009). Not only does it tell Marlon Green’s story in full, but it provides the backdrop of the civil rights struggle by interspersing highlights from the news of the time throughout the book.

Editor’s Note: This version contains corrections provided by Marlon Green’s daughter. We apologize for the errors.

The correct title of the book is Turbulence Before Takeoff: The Life and Times of Aviation Pioneer Marlon Dewitt Green.

Marlon Green attended Xavier Prep School. He corresponded with, and later married, a teacher at Xavier University, not one of his teachers from Xavier Prep.

The explanation of his complaint with the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission and Continental’s suit in Denver District Court was revised for clarification.

Cpt. Marlon Green was my dad’s, Marvin L Chachere’s classmate/best friend through OCS in the Air Force in Texas. My dad told me, Philip M. Chachere, on his dying death bed that Cpt. Marlon Green was the pilot who flew the Air Force plane that transported us from Japan to Guam in 1956, during my adoption to the U.S. Our family was best friend with Marlon’s family for years. Unfortunately dad passed away in 2012. I am forever grateful to Cpt. Marlon Green for helping me in my future life. RIP Marlon

Capitan Green was an inspiration to many black Americans. I was hired by Continental Air lines in 1967 and flew with Captain Green as member of his cabin crew.

Wow great info. As the top aveator in the aerospace industry my people are one of the first and largest black familys to homestead here in Denver . Thanks to pioneers like Green I soon became the first FAA A&P tech to get a pilot certificate and later become both a Ph. D and owner of a airline which I’m now turning into a spaceline with the FAA AST dept called Blue Ridge Spacelines. Thanks guys for doing what you do and showing me the way. Will name one of our spaceships afther you and Ed Dewight God bless. Dr. Doug Haynes 720-434-0183 http://www.blueridgeairlines.com. http://www.bluenebula.com

Thank you, Amanda Allshouse. I see you and appreciate you.