This Denver Art Museum (DAM) exhibition is the most comprehensive showing of Claude Monet’s work in 25 years, featuring 120 paintings spanning his entire career. Denver is the sole U.S. venue for this insightful presentation of the famous Impressionist’s work. The exhibit will be open through Feb. 2, 2020.

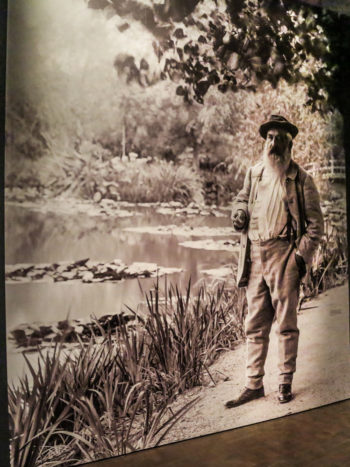

This photo of Monet shows where he greeted visitors in his garden at Giverny, with its Japanese-style footbridge (background).

“Above all, I wanted to be truthful and exact,” Claude Monet wrote about his painting. “He felt that to understand a subject, he needed to look at it every day and paint it from the same spot—to grasp the tone and spirit—the truth—of a place,” said Angelica Daneo, the Denver Art Museum’s curator of European art before 1900 and curator of Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, at the museum through Feb. 2, 2020.

The DAM exhibition, featuring 120 paintings, focuses on the famous French Impressionist’s relationship with nature and his response to the varied and distinct places he visited. “Visitors will gain a better understanding of Monet’s creative process,” said Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Mayer director of the DAM.

Monet (1840-1926) is best known for his landscapes and especially his waterlilies. But early in his career he specialized in caricature drawings of his teachers and other locals in Le Havre, in the Normandy region where he grew up. When he was a teenager, Monet began painting landscapes under his mentor, painter Eugène Boudin. Boudin opened his eyes to light and the love of nature, Monet said. From then on, Monet committed himself to understanding and painting nature. “The richness I achieve comes from nature, the source of my inspiration,” he said.

Farmyard in Normandy, 1862-63, one of Monet’s early paintings. At age 16 he met artist Eugène Boudin, who became his mentor. Boudin taught Monet “en plein air,” the techniques for painting outside.

Monet became a master at capturing quickly changing atmospheres, the reflective qualities of water and the effects of light. “Monet was indefatigable in his exploration of the different moods of nature,” said Daneo.

The exhibition features several of Monet’s most famous Paris scenes, including Boulevard des Capucines (1873-74), painted from a vantage point high above the street to convey the energy of the crowds. But his increasing interest in nature led him to abandon any human presence in his landscapes, immersing himself in nature. He moved with his family several times farther away from the city, following the Seine River.

Monet’s paintings of the Seine, many from the same vantage point at different times of day, were the beginning of his focus on series of the same subject. These series included his haystacks, poplar trees, Waterloo Bridge and waterlilies.

Charing Cross Bridge, Reflections on the Thames, 1899-1904. “What I like most about London is the fog,” Monet wrote. “It assumes all sorts of colors.” The painting depicts a misty, impressionistic London, with barges moving slowly and the Houses of Parliament barely visible in the background.

The painter’s extensive travels inspired many of the paintings featured in the presentation. He wrote that the rugged Normandy coast produced images of the sea with “a sinister and tragic quality.” The sunny Mediterranean enchanted him and inspired paintings of villas in bright, jewel-like colors.

Water-Lilies, 1913-14. Monet’s earlier waterlilies were realistic but his later representations were indistinct shapes that served to break up the reflections on the water. They show a freer brushwork that anticipates the abstract painting of the Mid-20th Century and inspired painters including Kandinsky.

Monet labored over his colors, writing, “Color is my day-long obsession, joy and torment. I chase the merest sliver of color…I want to grasp the intangible. Color lasts a second, or several minutes at most. Then they’re gone and you have to stop. Ah, how painting makes me suffer!”

A gallery of Monet’s winter paintings shows how he could transform white into a whole spectrum of colors.

Three different views of the Rock Needle on the coast of Normandy (1885-86). Monet’s series of the same subject reflected his desire to understand its essence. “One canvas was not enough to grasp the spirit of a thing,” said Angelica Daneo, DAM curator of the exhibition.

During the last years of his life, Monet created his gardens at Giverny, which he then translated onto the canvas. “He not only painted but created his own motif,” said Daneo. “His creative process established a unique intimacy with his subject.”

Monet ordered waterlilies no one had seen before, and he painted them repeatedly. While his earlier waterlilies were realistic, his later representations show a freer brushwork that anticipated the abstract painting of the Mid-20th Century. “He was an artist in two centuries,” said Heinrich.

Heinrich said children will enjoy this exhibition and be enriched by it. “They’ll experience Monet’s respect for nature, which is so important. And it will nourish their love for art, realizing that a painting is not a photograph.”

0 Comments