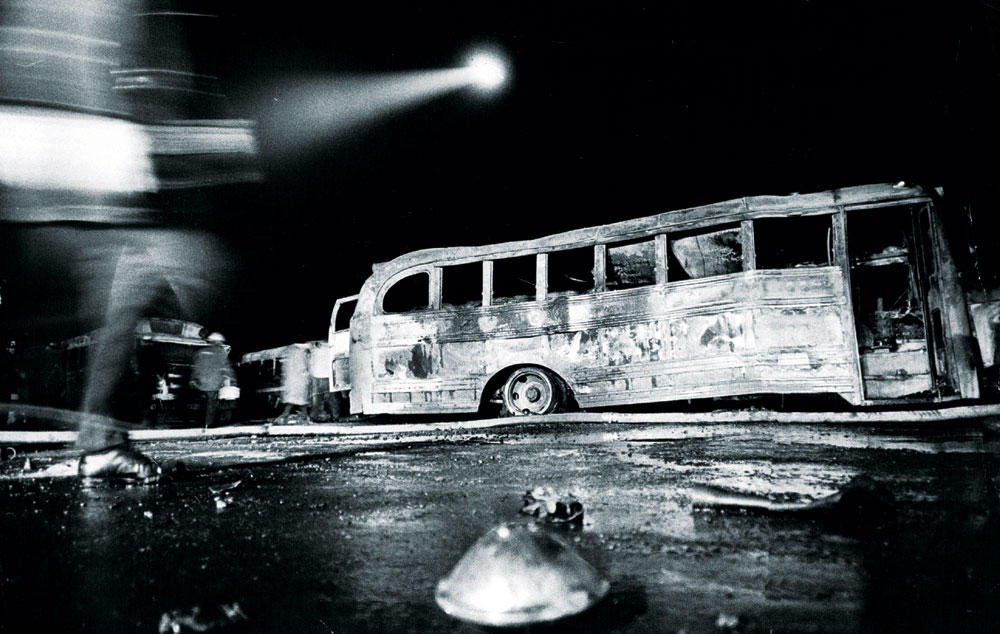

A light from a police helicopter shines down on some of the 38 fire-bombed buses at the DPS bus facility at 6th Ave and Federal on February 6, 1970. No one was ever charged with the crime. Photo by Steve Larson—Denver Post file photo

“Our nation, I fear, will be ill served by the court’s refusal to remedy separate and unequal education,” wrote Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. “For unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever learn to live together.” In the present moment of strained race relations wrought by profiling, police brutality and widespread distrust, Marshall’s 1974 admonition is as salient as ever.

Public schools have long been lauded as ladders of opportunity for the disadvantaged. Public schools have also been tasked with remedying segregation’s ills by teaching children not only how to learn, but to learn how to get along with people different from themselves. As the fastest growing urban school district in the nation and as the first northern district to undergo court-ordered desegregation, Denver Public Schools (DPS) is an important district to consider as our society reflects on how we might, in Marshall’s words, “learn to live together.”

September 2015 will mark 20 years since the federal court order mandating the desegregation of DPS was revoked. Eager to learn more about this chapter in Denver’s history, the Front Porch gathered leaders in Denver’s education community to discuss race and public education. The conversation was candid and hopeful, traversing topics ranging from bilingual education, affordable housing, and the challenges of recruiting faculty and staff of color. Ultimately, the participants agreed that although DPS has a long way to go to achieve equity for all members of its diverse population, the district has much to be proud of in its ongoing efforts to ensure every child succeeds.

Court-Ordered Desegregation

Denver’s desegregation history can be traced to the 1960s in the Park Hill neighborhood, where area activists challenged the school board’s system of gerrymandering enrollment zones to segregate Anglo students from African American and Latino pupils. These challenges culminated in the landmark Keyes v. Denver School District No. 1 (1973) decision. The court sided with the plaintiffs in Keyes, reasoning that Denver’s educational segregation was not only the result of housing trends, but that the school board had deliberately “created or maintained racially or ethnically segregated schools throughout the district.” This separation, as the court had famously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and as the plaintiffs aptly demonstrated in Keyes, was inherently unequal.

Denver’s desegregation history can be traced to the 1960s in the Park Hill neighborhood, where area activists challenged the school board’s system of gerrymandering enrollment zones to segregate Anglo students from African American and Latino pupils. These challenges culminated in the landmark Keyes v. Denver School District No. 1 (1973) decision. The court sided with the plaintiffs in Keyes, reasoning that Denver’s educational segregation was not only the result of housing trends, but that the school board had deliberately “created or maintained racially or ethnically segregated schools throughout the district.” This separation, as the court had famously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and as the plaintiffs aptly demonstrated in Keyes, was inherently unequal.

Dr. Evie Dennis

Indeed, the quality of schools across Denver’s city core varied by racial population; inexperienced and probationary teachers were assigned to schools with large minority populations and these schools were both overcrowded and lacked the resources that the predominantly white schools enjoyed. To remedy these disparities, the court ordered a districtwide policy of desegregation. For more than 20 years following this momentous decree, DPS operated under the watchful eye of a federal judge—even as they worked in consultation with court-appointed consultants to design plans aimed to combat the effects of segregation.

These plans included the most common and most controversial provision of the era: busing. Although busing—removing students from their neighborhoods and transporting them to schools across the city to create more racially balanced student populations—became the symbol of opposition to desegregation in Denver, there was much more to the district’s desegregation strategy. Other provisions included access to bilingual and bicultural education, affirmative actions taken to hire more faculty and staff of color, and the reallocation of district resources to improve the quality of school facilities across the city. Dr. Evie Dennis, who was part of the DPS community relations team tasked with implementing the desegregation order, pointed out that it was only when Superintendent Lou Kishkunas’ daughter got bused to Cole Junior High—a formerly segregated school—that Cole “got new books, got painted, and got cleaned up.”

Happy Haynes

“Shining a Light”

“Sometimes the changes were painful,” admits DPS alumna, former city councilwoman and current school board member Happy Haynes, “but one of the things desegregation does is shine a light.” Haynes remembers her experience as a top student at Barrett Elementary, who then went to Gove Middle School and had to “scramble to compete” with white students. Although Haynes found the initial adjustment to an integrated atmosphere unnerving, she now identifies it as a source of her self-confidence. “For black and Latino kids in this environment . . . you found out you were just as good as they [whites] were. And you could see the difference in preparation, but you also said, ‘That’s okay. I can do that.’”

Rita Montero, DPS alumna, parent, and former school board member, suggests that the benefits of desegregation extended to the district’s white students as well. “What it did for white kids was to force white kids to be in an environment with black kids and Latinos. And they loved it! And now whites talk about it as older people as ‘the good old days.’”

Current DPS parent and former school board member Mary Seawell explains that, imperfect as its implementation was, the “court order made this something to talk about and people got angry and people were engaging and they were talking about their values around integration and democracy and what it all meant.”

Rita Montero

Dividing the City

This elevated public dialogue and these integrated life experiences did not come without great costs, however. As Denver’s school desegregation case made its way through the courts, arsonists destroyed one-third of the district’s school buses; a pipe bomb exploded on the front porch of the lead plaintiff in the case, and a bomb also went off in the district offices.

“What almost killed the district,” according to DPS alumna, parent, and former school board member Sue Edwards “was the families who fled to the suburbs.” Laura Lefkowits, also a former school board member and DPS parent, agrees. She refers to this flight as “the abandonment by the middle class of Denver Public Schools,” explaining: “We lost 30,000 kids in the first decade as a result of busing and they were almost all white or middle-class kids. They were families that had options.”

Laura Lefkowits

Not long after families began fleeing to the suburbs to escape court-ordered desegregation in the city, Colorado voters passed two amendments that would ensure the DPS desegregation order would not affect other Colorado districts. The Poundstone Amendment prohibited Denver from annexing the surrounding suburban areas and Amendment Eight stipulated, in part, that no “pupil be assigned or transported to any public educational institution for the purpose of achieving racial balance.” These two pieces of legislation, both passed by the 1974 state legislature, effectively isolated the federal desegregation order to the city of Denver.

Sue Edwards

As the decades wore on, the desegregation order became unpopular among even those communities it was most tailored to benefit. Rev. Aaron Gray, a former school board member and later employee on DPS’s Community Relations team, explains his eventual opposition to the desegregation order as “not so much anti-busing as more that communities needed to be restored and communities needed to be built up… one of the things that gives a community pride is that it can identify ‘our schools.’” Related to the notion that communities rally around their neighborhood schools, is the idea Gray wanted to “affirm for the kids: that they did not have to leave their communities and go somewhere to go to school and then come home,” which he thinks sent the message that their neighborhoods were inferior.

Lessons Learned

Mary Seawall

In September of 1995, Federal Judge Richard P. Matsch released Denver from the desegregation order, explaining that the “Denver that is now before this court is very different from what it was when the lawsuit began.” Matsch acknowledged, “The current mayor of Denver is black. His predecessor was Hispanic. A black woman has been superintendent of schools. Black and Hispanic men and women are in the City Council, the school board, the Colorado Legislature and other political positions.” The city’s diverse leadership, Matsch reasoned, was now capable of ensuring resources were more equitably divided among the district—a decision influenced, in part, by Mayor Wellington Webb, who favored an end to busing because of the negative impact it had on the city.

Both the city’s leadership and the racial composition of DPS had changed dramatically during the busing era. Not only had the student population declined by more than 30,000 pupils, by the mid-1990s two-thirds of district’s population were racial or ethnic minorities. This demographic reversal, coupled with the return to neighborhood schools, has only compounded the racial isolation of DPS students in the last 20 years since the desegregation mandate was revoked. Today, fewer than 20 percent of schools across the district would meet the former court-ordered criterion that “required DPS to maintain a ratio of the races that was plus or minus 15 percent of the district average,” explains Lefkowits.

Firemen hose down the buses in the February 1970 bus bombing. No one knows who did the bombing and no one claimed responsibility, but it has been assumed that it was related to racial tensions.

Photo by Steve Larson—Denver Post file photo

Landri Taylor

And yet, DPS confronts this racial isolation armed with wisdom won from experience. Gray, for instance, underscores the need for “consistent leadership,” recalling that the frequent turnover among DPS superintendents during the busing era impeded the desegregation order’s success. Lefkowits suggests further that “the district never had consistent positive leadership that would call people out on their racism,” even as she praises the present board for explicitly acknowledging the district’s opportunity gap. “You’ve got to call it out, you’ve got to name it,” says Haynes, referring to the marked disparity in graduation rates as well as reading and writing proficiency between the district’s Anglo and its African American and Latino students. The board’s five-year strategic plan, the “Denver Plan 2020,” pledges to narrow this chasm.

Alongside the need for consistent positive leadership, Seawall suggests that Denver’s history teaches us “that you can’t just put kids together in a building and think it’s going to all be okay.” Instead, “You really have to be intentional about creating school cultures that are aware and dedicated to having all kids empowered, if you really want to have successful integration.” DPS grandparent, parent and alumnus Chris Martinez concurs: “You can put people and resources into every school,” but “you’re not going to get the same results if you don’t change the cultures within those buildings.”

Chris Martinez

Those cultural changes—of high expectations for each child, of support and resources to help every child

Rev. Aaron Gray

succeed, and of valuing the unique perspectives diversity engenders—are nurtured through broader societal dialogue, agreed the discussants. “The most productive thing,” recognizes current school board member Landri Taylor, “is having these conversations in a way that we have no fear.” Rich uninhibited dialogue is what helps make “Denver a great city,” according to Dr. Evie Dennis, who became the district’s first female and first African American superintendent. “I still believe in it,” Dennis says of the district she helped navigate through the uncharted era of desegregation. “I still have great belief in the school system, I really do. As I look at school districts across the country, Denver can be proud. We can be proud,” declares Dennis.

Stapleton resident Maegan Parker Brooks, PhD, is writing a book about debates over the desegregation of public schools in the American West. She will be moving to Oregon to join the faculty at Willamette University this fall.

0 Comments