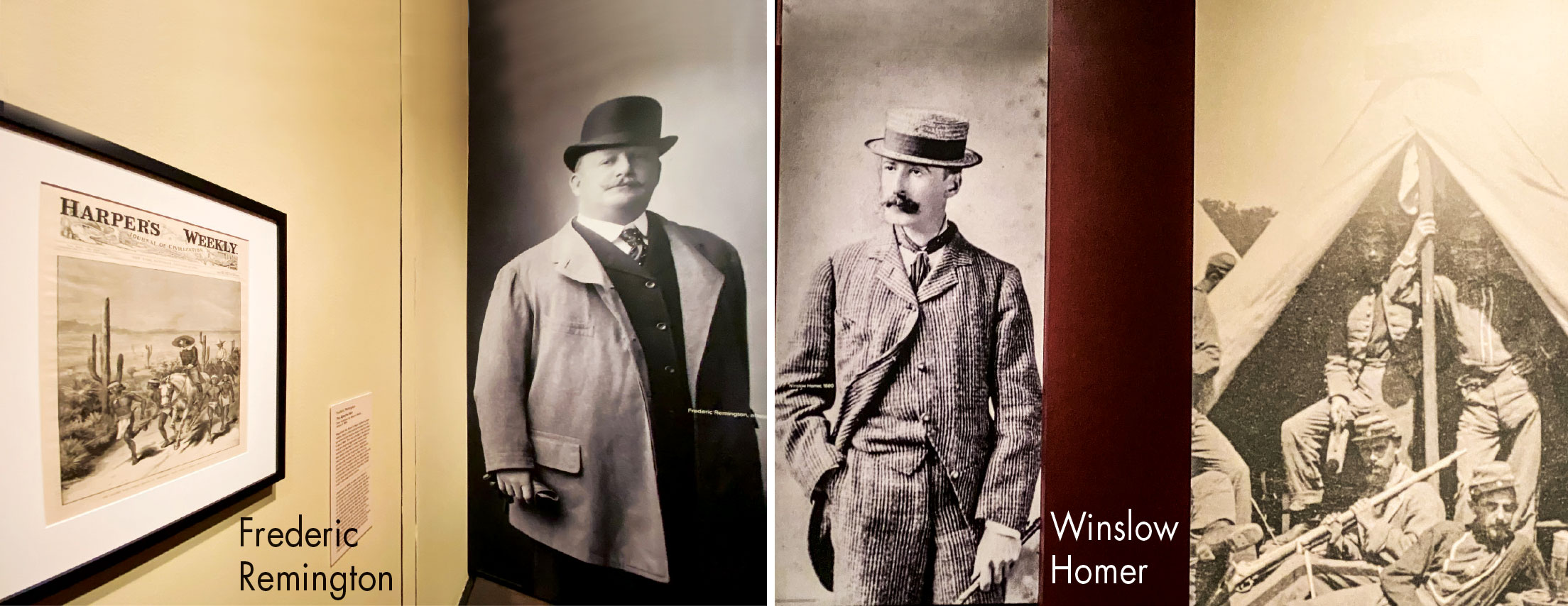

Natural Forces: Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington connects the work of two acclaimed American artists during the changing times around the turn of the 20th Century. Above: Remington’s The Cheyenne, ‘burning the air’ with all four hooves off the ground.

Frederic Remington (1861-1909) created images of the American West that still define our notions of the cowboy. Winslow Homer (1836-1910), considered the most original painter of his time, created masterful depictions of the Eastern Seaboard.

For the first time, works of the two masters are brought together side-by-side at the Denver Art Museum through June 7. Included in the exhibition are 60 works, including paintings, illustrations and bronze sculptures.

For the first time, works of the two masters are brought together side-by-side at the Denver Art Museum through June 7. Included in the exhibition are 60 works, including paintings, illustrations and bronze sculptures.

“Did they ever meet? We know they shared a love of narrative art [art that tells a story] and illustration, but we don’t know whether they knew each other,” says Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Meyer Director of the DAM.

Remington re-worked his oil painting, The Old Stage-Coach of the Plains (1901), into a cover illustration for The Century Magazine in 1902.

The exhibition showcases the works of Remington and Homer, connected by the time in which they lived. Born a generation apart, both artists captured the American spirit during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “They were seeing the same time period from different parts of the country and through their different personalities,” says Erica McIntire, senior vice president at Bank of America, a sponsor of the exhibit.

Both artists started their careers as war correspondents, working on the frontlines and publishing their illustrations in Harper’s Weekly, a popular magazine. Homer captured the American Civil War by illustrating battle scenes and camp life. Remington produced illustrations related to Geronimo and the American Indian Wars and, later, the Spanish-American War.

The Fall of the Cowboy (1895), Frederic Remington. The cowboy era is gone as a fence restricts the open range. This is an elegy for the cowboy.

“While photography existed before the Civil War, there was not yet the reproductive technology to print photos in publications,” says Jennifer Henneman, associate curator of Western American Art at the DAM. “The illustrations told a visual story, conveying the drama and power of the moment. They channeled both feelings of loss and of hope.”

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century era was a time of growing industrialization, urbanization and modernization. Remington and Homer shared a connection to the Adirondack mountains in upstate New York, where they went to escape urban life and enjoy hunting, fishing and the wilderness. “Their depictions of beauty and peacefulness were popular with urban audiences,” says Henneman. “The paintings were nature therapy for city-dwellers: If they couldn’t be there themselves, they could look at the art.”

Sunset on the Plains (about 1905), Frederic Remington. One of Remington’s nocturnes, here the sun is going down on a vanished culture.

But nature is not always solace, as both artists demonstrate in the Natural Forces section of the exhibition. “Nature is a force to be reckoned with, a challenge to test oneself against,” says Henneman, pointing to Homer’s Undertow and Remington’s Dash for the Timber.

The final gallery examines the somber and psychological works of the two artists toward the end of their lives. “Now they had shed their documentary roots for pure art,” says Henneman. “In the 1880s and ‘90s, Remington knew the American Western frontier was closing and the wilderness was disappearing. His paintings allude to the anxieties of the time, especially for men. In Who Comes There, the riders are looking at something outside the frame. He left something out for the viewer to take away.”

Homer’s Fox Hunt (1893) is similarly mysterious, depicting a fox seemingly pursued by crows. “Are the crows hunting the fox?” asks Henneman. “One explanation is that the fox is Homer himself, in isolation after he moved to rural Prouts Neck, Maine from New York City.”

West Point, Prouts Neck (1900), Winslow Homer. The painter spent many days getting the high sea and tide just right. He considered this his best work.

Homer and Remington created some of their greatest works from the 1880s into the twentieth century, says Henneman. “Homer began to experiment with watercolor and Remington with bronze. Homer, well established as an artist, painted selectively and marketed his work until his death in 1910. The younger Remington desired the same kind of critical acclaim and worked prolifically to produce paintings for his solo shows in New York until his unexpected death in 1909 at age 48.”

Left: Watching the Breakers (1891), Winslow Homer. Two women stand in this crashing seascape, gazing toward the water. In their statuesque poses, the women are symbols of strength. Right: Undertow (1886), Winslow Homer. The waves feel vibrantly alive, while the sculptural figures seem emotionally disconnected, as if each is alone with his destiny.

0 Comments