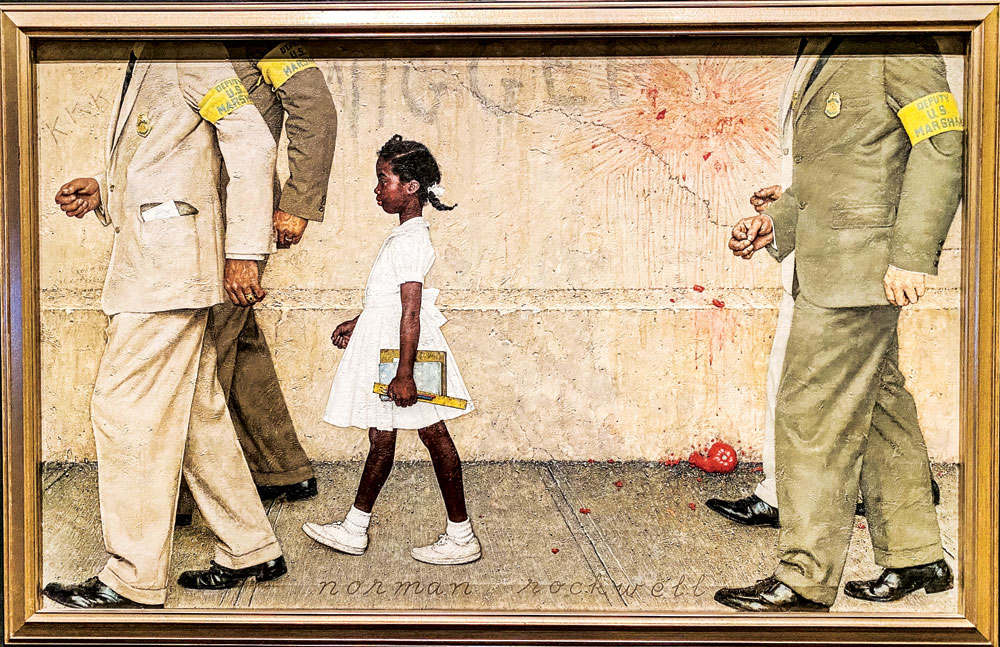

In the image The Problem We All Live With, 1963, for Look magazine, Rockwell depicts 6-year-old Ruby Bridges’ march to her first day at an all-White New Orleans school in 1960, escorted by US marshals. Bridges, the first Black child to desegregate a Southern elementary school, was shielded from the violent crowds protesting her attendance.

“I just wanted to do something important,” Norman Rockwell wrote in his autobiography. The famous illustrator strived to use his considerable skills as a tool for good.

A talented visual storyteller, Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) captivated the popular American imagination with his advertisements, posters, and magazine illustrations. Displayed in the exhibit entryway are some of the 300 cover illustrations he created for The Saturday Evening Post between 1916 and 1963.

“He was empathetic to the core,” says Timothy Standring, curator of Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom, on display through Sept. 7 at the Denver Art Museum. “We show Rockwell as not just a brilliant illustrator, but also a gifted storyteller who was socially involved.”

––– CLICK HERE TO VIEW A VIDEO OF THE EXHIBIT –––

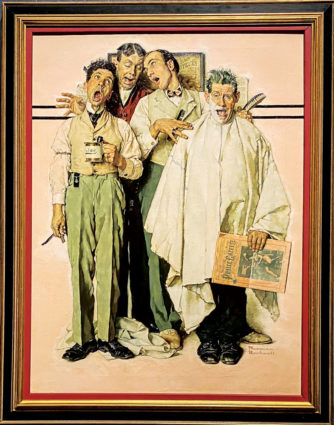

Barbershop Quartet was the cover of The Saturday Evening Post, Sept. 26, 1936. Rockwell’s lovable characters made him a household name.

Rockwell’s most famous works, including paintings that became covers for The Saturday Evening Post, show his penchant for lovable characters and domestic ritual. His later illustrations address the harsh realities of racism and violence in America. The exhibition includes videos and historical documents. “This is a different kind of show for the Denver Art Museum, a hybrid between art and history,” says Standring.

Standring calls it “prescient” that the exhibition was planned four years ago to run this year. He says it was intended to stimulate discourse in the election year. But the events of 2020 make the timing optimal to stimulate thought and discussion around racism and human rights. “Even our banner image, the multi-racial The Right To Know, connects the show’s subject matter to what’s going on in 2020,” says Standring.

Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter, 1943, became the heart of a World War II campaign aimed at recruiting women for defense industry work.

Rockwell was slated to open May 1, but the coronavirus lockdown closed the museum until early July. For the new opening, a few works were eliminated to allow more space for social distancing. In addition, Rockwell designers added prompts throughout the galleries, highlighted with thick yellow stripes to draw attention to questions on the theme “Has Anything Changed?”

“The bilingual prompts are intended to stimulate critical thinking and dialogue around such issues as racial and economic equality, privilege and war,” Standring said.

The exhibition includes about 125 works and opens with Rockwell’s depictions of American life during the Great Depression of the 1930s, a time of economic hardship. Despite the Nazis’ aggression in Europe, most Americans were concerned about solving domestic problems and reluctant to get involved in the war. President Roosevelt hoped to garner support for the war by proclaiming “four essential human freedoms” as a basic standard not just for America, but “everywhere in the world”: freedom of speech and worship, and freedom from fear and want.

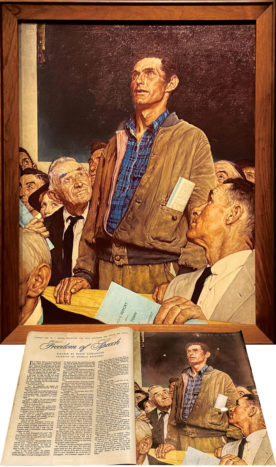

Freedom of Speech depicts a lone dissenter’s remarks at a town meeting. Rockwell appears in the scene at the corner of the blackboard to the left. Below the painting is the 1943 Saturday Evening Post article with the illustration.

A video shows Roosevelt’s impassioned Four Freedoms speech in 1941. It was followed by an aggressive propaganda campaign, but support for the war still lagged until Rockwell published his Four Freedoms illustrations in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943. Using his Vermont neighbors as models, Rockwell depicted the four freedoms in everyday scenes. “He controlled the settings, the light and the staging,” says Standring. “The paintings are brilliant visually in a way that speaks to us.”

The Four Freedoms paintings sparked investment in the war. But the faces depicted were overwhelmingly white, drawing criticism from Americans who wondered if the four freedoms applied to them. “[Your] posters . . . have crystallized in the minds of Negroes the realization of freedoms denied in large measure to most of them,” wrote Roderick Stephens, Chairman of the Bronx Inter-Racial Conference, in a letter to Rockwell in 1943.

For the duration of the war, Rockwell’s illustrations emphasized people rather than battles, creating a rich and poignant documentation of the time.

In the 1960s, Rockwell threw himself into the documentation of social issues. When he left The Saturday Evening Post in 1963, he was finally able to correct the editorial prejudices that had permeated his work. For example, Rockwell once had to paint out a Black person in a group picture because of the Post’s policy that people of color appear in service-industry roles only. The more progressive Look magazine allowed him to create forthright and confrontational images of racism, human rights violations and calls for moral decency.

Paintings including The Problem We All Live With, The Golden Rule, Blood Brothers and The Right To Know promote his progressive ideas on civil rights, human rights and global equity.

Rockwell painted Freedom from Fear while Europe was under siege. If not for the headline on the father’s newspaper, it might be read as a peaceful bedroom scene. Rockwell wanted to convey the promise of safety.

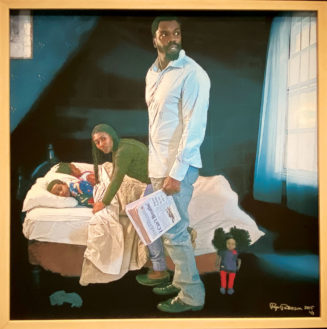

Freedom from What? (I Can’t Breathe), 2015, by artist Maurice “Pops” Peterson. Peterson’s take on Freedom from Fear explores the idea that not all American families enjoy the privilege of safety, and depicts a newspaper headline with the words “I Can’t Breathe.”

![]()

The final gallery presents contemporary artists’ reactions to Rockwell’s work, including re-creations of his Four Freedoms as more representative of diverse races, cultures and sexual orientations. Shepard Fairey’s We the People poster series features portraits of women of different racial and cultural backgrounds, reinforcing and updating Roosevelt’s four freedoms concept for today’s America.

“We hope this presentation helps us all to reflect on our assumptions,” says Standring. “Maybe we haven’t done some things right as a country. Some people will be uncomfortable, but it’s a dialogue we need to have, with civility.”

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments