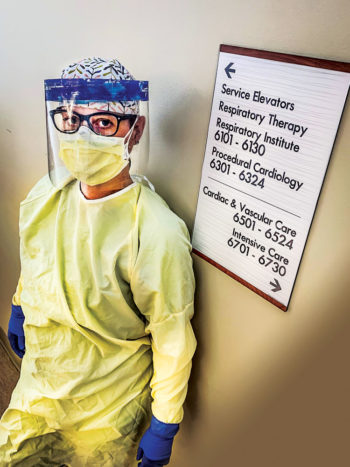

“This is a very serious disease still,” says Dr. Tim Tran, an anesthesiologist specializing in cardiothoracic critical care at UCH, “and I think that the unnecessary risk right now of carrying the virus and passing it to other people is still very high.” Photo by Dr. Madiha Yazdani.

The 1980s anthem “Don’t Stop Believin’” has taken on new meaning for Kimberly Schmitten, an RN at St. Joseph Hospital in Denver. “It is the greatest feeling,” she says, when she hears Journey’s familiar tune over the hospital intercom at the end of a day. The song signals that there’s been a success in the hospital’s efforts to help a patient overcome COVID-19. “Success” may mean that a patient has been extubated and can leave the ICU to step-down care.

Within two days of Gov. Polis’ April 3 recommendation that Coloradans wear masks in public, the Jacobson family donned homemade masks they had just been given by a neighbor. TJ (right), a first responder, pushes Liam, 4. Brooke (left), pulling Brittany, 7, and January, 1, works from home, so the stay-at-home restriction has impacted their lives less than for so many others. Brittany had no problem adapting. Her view: “I love being with my family all the time.”

Ode to Nurses: Artist Austin Zucchini – Fowler created a larger-than- life mural of a nurse wearing boxing gloves as a tribute to the frontline workers. It’s visible driving west on E. Colfax in the alley at Williams.

“People hear that it’s a virus and think that we’re being overly cautious, but it’s not like the flu…It really goes for your lungs….and it’s way more deadly,” says Schmitten, a Stapleton resident who has been working in the ICU as needed since the pandemic began. She volunteered to care for COVID-19 patients as an ICU Extender, a support position for ICU nurses.

She had misgivings and fears before taking on this new role, but her calling as a nurse ultimately took precedence. “It’s like, if you have a lifeboat and everybody is drowning…why would you not help. I am able to help people when they really need me now.” Though she feared getting the virus herself or possibly passing it on to her family, “Once I got over that initial fear, my drive to help this community kind of took over.”

She loves the new mural of a nurse in boxing gloves on E. Colfax, and says nurses think the image is “awesome” and “motivating.” One co-worker, however, says she “doesn’t want to be hero-worshipped, and wishes people would focus their energy on fixing the problems that the government had in response to the virus.”

Schmitten follows a thorough decontamination routine after work, leaving her scrubs at the hospital, wiping down her car, and showering “before I even breathe in the general direction of my husband and my kids.” Schmitten says the speed with which the disease progresses is frightening. People may walk into the Emergency Department short of breath and need to be intubated a few hours later. Intubation in turn requires sedation to synchronize respiration with the ventilator, and patients are kept in isolation.

Schmitten, who works at St. Joseph Hospital, bristles at comparisons to the flu: “It’s not like the flu. It’s much more contagious, and if it hits you hard, it’s far more deadly.” Photo by Jessica Patel, RN.

Both Schmitten and Dr. Tim Tran, who is an anesthesiologist specializing in cardiothoracic critical care at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), say that it takes several nurses as well as a respiratory specialist to turn a patient, which has to be done every two hours. To minimize exposure, the medical team must be extremely efficient in all of its interactions. For the 2-3 weeks someone is on a ventilator, contact is minimal, a reality that is exceptionally hard on family waiting at home for news, as well as for healthcare workers.

Schmitten reflects on one of her patients, whose wife called her frequently for updates on his condition. She learned about his life and family through their conversations, and when she went into his room, “even though he was intubated and sedated, I would talk to him about his wife and kids,” she says. She hoped that hearing his name and a kind voice talking to him about his wife and children would somehow reach the sedated man. He has since been extubated and Schmitten hopes he gets to return home soon.

While patients and their families long for a return home, a small vocal minority is getting impatient staying at home. April’s protests over the stay-at-home orders in Denver and elsewhere disturb and sadden these healthcare professionals. “It’s personal. I am putting my life and my family on the line to protect the community, and for them to completely disregard it, gathering in large groups, not wearing masks, it’s a slap in the face,” says Schmitten.

“I am empathetic to people who want to be independent and return to ‘normal,’” says Tran, who lives in Stapleton. He cautions, though, that “this is a very serious disease still, and I think that the unnecessary risk right now of carrying the virus and passing it to other people is still very high. We don’t have great labs yet to consistently test fast and test everybody so I’m kind of saddened by that [the protests].”

When she’s not caring for COVID-19 patients, Kimberly Schmitten cares for her 7-month old twins with her husband, Chris. He is active military but now provides “daddy daycare” so she can serve on the frontlines. Photo by Micheal Anderson.

Intermittent news stories about different medications and treatments offer flashes of hope, but Tran says at this point “There’s no silver bullet. As of now there’s nothing that’s a guaranteed cure or treatment for any of this.” In early April, UCH became the first Colorado hospital to treat a COVID-19 patient with convalescent plasma. To date, 17 patients at UCH have received transfusions of convalescent plasma, but data on outcomes is insufficient at this point and more plasma donors are needed, according to Jessica Berry, Senior Media Relations Specialist with UCH.

Tran sees room for optimism as the curves in New York and Washington states slowly flatten. “We can overcome the pandemic with appropriate measures,” he says. Unlike the Journey song, however, beating this disease is not merely a matter of “believin’.” Re-opening businesses and beginning a return to “normal” will require more testing capability than currently available in Colorado. “You would need 1) the ability to test for the virus itself rapidly and widely and 2) the ability to test for the antibody levels as well, to see if you actually developed some kind of immunity,” says Tran.

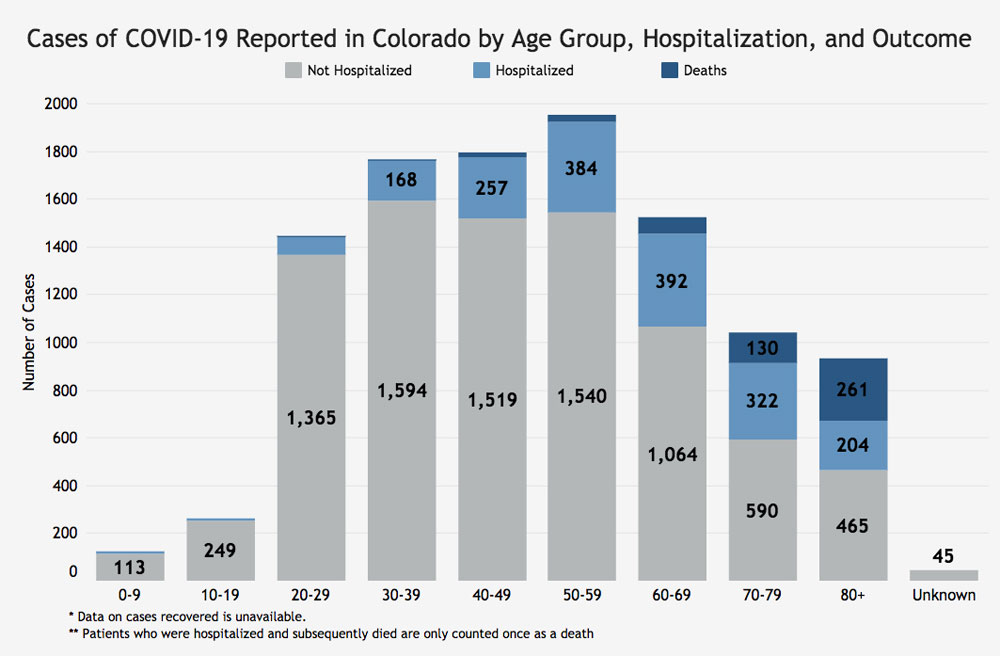

Colorado Hospitalizations and Deaths Due to COVID-19

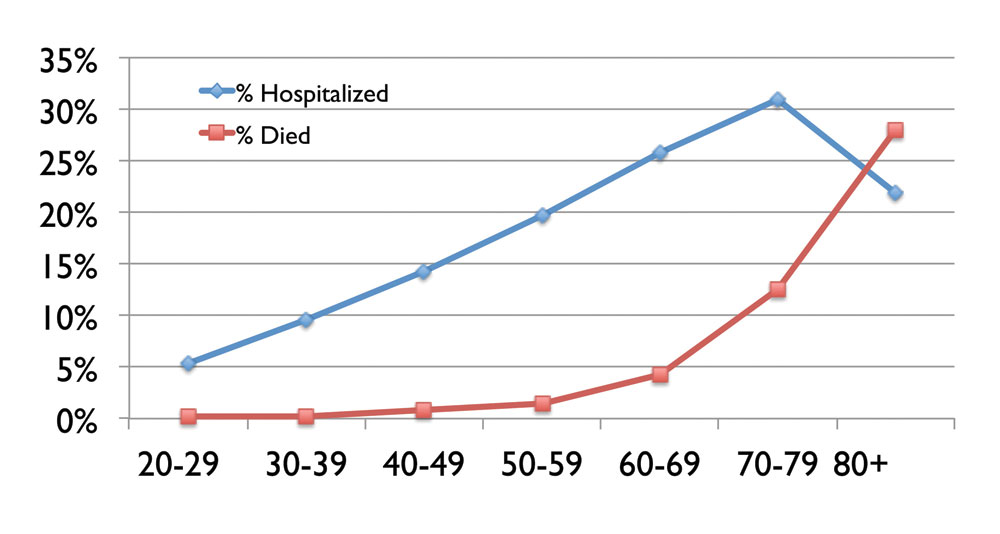

These statistics as of April 23 show the percent of Colorado COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized or died in each age range. While the risk of death remained relatively low before age 50, then jumped dramatically, the rate of hospitalization increased steadily from the 20s to age 70.

0 Comments