Each month, the Indie Prof typically reviews one or more films from the theater or an instant-streaming service. This month he instead shares his views on the Oscars.

Each month, the Indie Prof typically reviews one or more films from the theater or an instant-streaming service. This month he instead shares his views on the Oscars.

Follow “Indie Prof” on Facebook for updates about film events and more reviews.

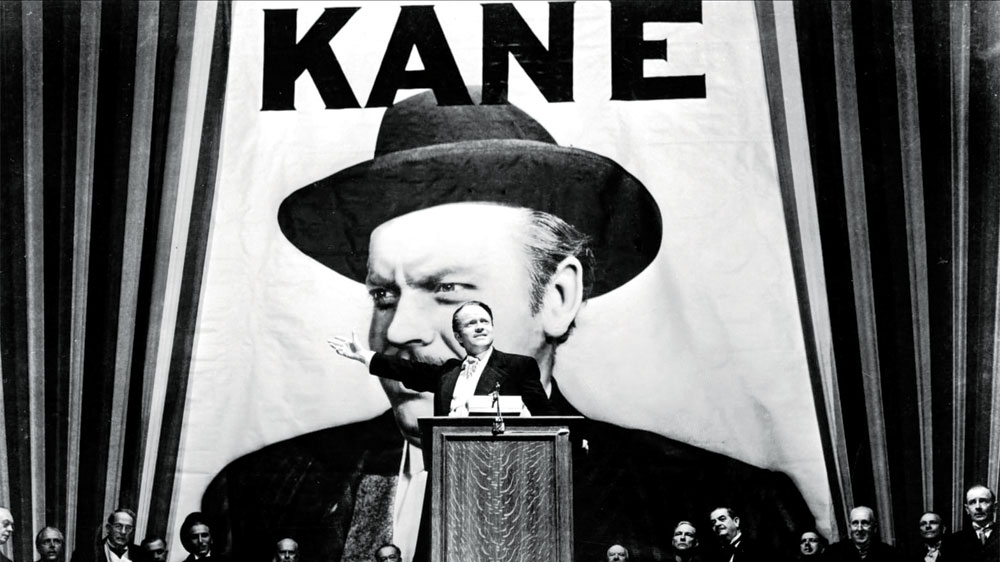

At the 14th Academy Awards in 1942, the Oscar for Best Picture went to How Green Was My Valley, directed by John Ford. It was Ford’s fourth Oscar for Best Director. The Awards themselves would have been forgettable if not for one vote: How Green Was My Valley beat Citizen Kane that year. Of course, Citizen Kane is now generally considered the greatest film ever made (a moniker this critic endorses). The reasons why Citizen Kane did not win are many, and most concern the treatment of its subject: William Randolph Hearst. Hearst was the biggest media tycoon of the era, and he bullied exhibitors into ignoring the film while keeping it out of his papers entirely. His efforts effectively denied the film any real exposure, and even its inclusion at the Oscars seemed to be a transgression. Still, Academy members were able to screen it and chose otherwise. This was just the beginning of politics infesting the Oscars.

Citizen Kane

In 1981, Ordinary People, directed by Robert Redford, won the Best Picture award while Redford won the Best Director award. Today, the film is hardly memorable; more memorable is the fact that Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull lost (and Scorsese lost as well). Today, Raging Bull is considered one of the ten best films ever made. Once again, the reasons for this slight are complicated: the film was controversial because of its violence, and coming on the heels of the also violent/controversial Taxi Driver a few years earlier, America was having a societal discussion about violence in general and at the movies in particular. But the less public issue was that Scorsese had been fighting the studios for several years over the use of cheaper color film stock and developing processes. The studios did not like Scorsese’s activism.

The political aspects barely scratch the surface of Oscar’s issues. The voting system is highly problematic and fraught with cronyism and voters overloaded with information. The Academy includes over 8,000 voting members consisting of past winners and others who can petition for voting rights (if you have previous film credits). The nominations are chosen by peers in each category: actors vote for actors, directors for directors, editors for editors, etc. Everyone gets to vote for Best Picture nominations, and everyone gets to vote for the winners in all categories. Therein lies the problem.

One voter who released his/her ballot this past year, highlights how the voting process can be so unseemly and downright ignorant. The voter stated they did not like Greta Gerwig’s Little Women because “English actresses had been chosen to play Americans, and that the characters all complained about how poor they were when they lived in a nice house with a cook.” Huh? Did this voter not know that the film was based on a book? The story has been around for over 100 years. And the voter was only responding to aspects of story, not acting, directing, cinematography, editing, costume design, production design, etc. It is entirely myopic, not to mention uninformed.

Another voter responded to the de-aging technique used in The Irishman. They abhorred the process and noted that “Francis Ford Coppola had rightly used different actors of different ages to play the same character in The Godfather.” Again, Huh? Yes, both Robert DeNiro and Marlon Brando played Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather, but that was in two different films! They were never in the same film. And besides, what does that have to do with the overall film anyway? The film was judged based on one small aspect.

These are just two anecdotes from this year’s Oscars, but stories abound about how members go about choosing the winners. Should 8,000 people, from 17 different areas of specialty, choose the winners in all categories? Should actors choose the winner for Best Cinematography or Best Sound Editing? Some may be well qualified, to be sure, but my guess is most are not. In my opinion, the award for Best Picture, for example, should not be subjective at all—it should be the film that is best in all categories—the sum total of Best Screenplay, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Editing, Best Acting, and so on. It should be an objective choice, and too many people who may not have the expertise, time, and/or all-around film knowledge are deciding the outcome. And that doesn’t even broach the issues of inclusivity, which have become more egregious in recent times.

What to do? I propose a voting system more akin to the nominating process where experts in the category vote for the winners. Still, that process exposes the voters to politics and pressure campaigns of voting for a specific studio film when your livelihood depends on that studio. People may vote according to who pays them. The voting for the winners, then, should be relegated to another set of jurors, much like the jury system used at film festivals, and consisting of 9 people in each category who must meet, in person, and decide the winners through discussion (like a jury!). The jury should consist of at least 5 members of the nominating category (5 editors for editing, etc.) but the remaining 4 should be outside the industry completely: critics, film academics/historians, and/or others without a vested business interest in the industry. For Best Picture, 5 of the jurors should come from a random sample of the 17 categories along with 4 outsiders. The jury should also be representative of the world population in terms of race, gender, ethnicity, etc. The 9 jurors must decide together, face-to-face, eliminating the possibility that they had not seen the film. The majority rules in the jury room.

To be fair, Hollywood in general has been historically progressive, and the Academy has made strides in recent years to include more women and people of color in response to non-inclusive membership and results. Those efforts are laudable, and the selection of Parasite this year is a small step in the right direction. In addition, most members have earned their voting rights, and it would be a bitter pill to take that away. Many are worthy, knowledgeable, and objective; however, the results over the decades have tainted the process, and it is time for a new direction with a fairer process.

The Oscars have always been encumbered by politics, misinformation, disinformation, sexism, racism, and downright ignorance. That needs to change if the Awards are to remain relevant.

The Oscars have become the movie version of Iowa’s role in politics—too white, too bloated, and too concerned with tradition. But it can change.

Vincent Piturro, Ph.D., is a Professor of Film and Media Studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver. He can be reached at vpiturro@msudenver.edu. And you can follow “Indie Prof” on Facebook and @VincentPiturro onTwitter.

Love the article. I totally agree with the concept of changing the voting procedures to make it a fairer process.