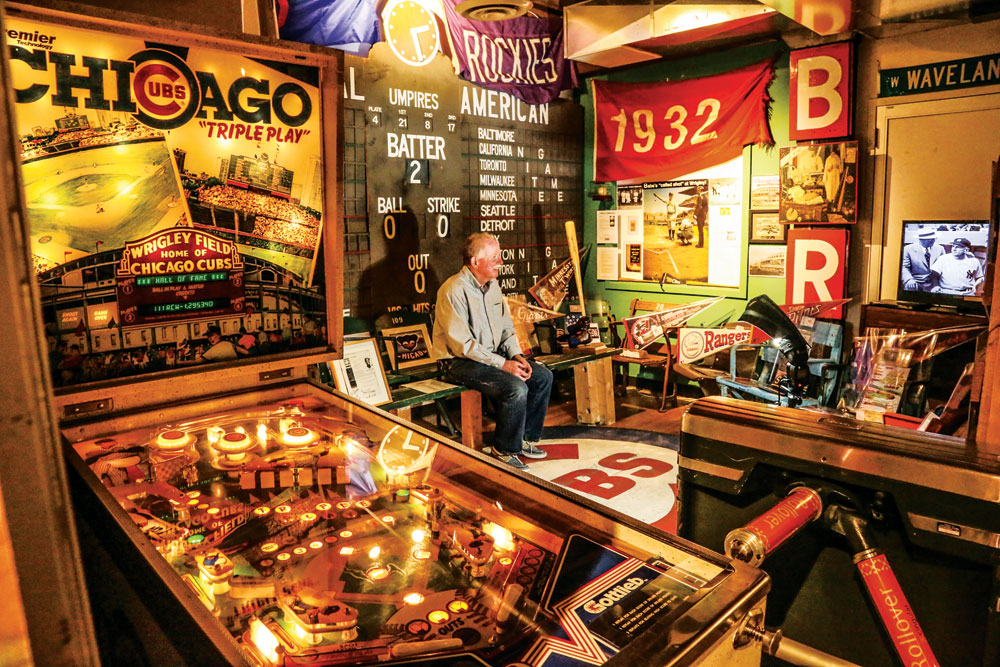

The author goes back in time in the museum’s area devoted to Wrigley Field and the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs pinball game in the foreground is one of the museum’s treasured acquisitions. A miniature reproduction of Wrigley’s famed hand-operated scoreboard dominates the room, which includes the home team’s on-deck batting circle.

Bruce Hellerstein stands at the door of The National Ballpark Museum located on Blake St., a block west of Coors Field. A Rockies game and visit to this treasure trove of memorabilia would satisfy the most baseball-hungry fan.

When I walked through the front door of the National Ballpark Museum I was instantly transported to the days when I was a 14-year-old baseball fanatic, rushing down to the local drugstore to buy a copy of Street & Smith’s pre-season magazine, to hours spent playing the table-top baseball game APBA (motto: “Say App-bah”), to my misplaced fixation on memorizing the starting lineups of all sixteen major-league teams.

Bruce Hellerstein stands at the door of The National Ballpark Museum located on Blake St., a block west of Coors Field. A Rockies game and visit to this treasure trove of memorabilia would satisfy the most baseball-hungry fan.

It’s Bruce Hellerstein’s fault. Known to one and all as “B,” Hellerstein is creator and curator of the museum, housed in a storefront at 1940 Blake Street, a long fly ball from Coors Field. The CPA is a certified baseball nut (he once constructed a miniature field in his backyard), but his real passion is old ballparks, like Crosley Field in Cincinnati, Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park in Chicago, and the Polo Grounds in New York City.

“This is what I tell people in the museum,” he said, enthusiastically launching into his favorite subject. “What they are seeing with these old-fashioned parks you will never, ever see them again because the league would never approve of them for all the different distances and having batting cages in the middle of centerfield (as at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh) or whatever it might be. They won’t do it.

Stadiums, current and former, are the focus of the National Ballpark Museum near Coors Field. Hundreds of photographs, bricks from long-gone parks, turnstiles, signed baseballs, and other memorabilia fill several rooms. Chicago won the National League pennant in 1932, lost to the New York Yankees in the World Series, the one in which Babe Ruth is said to have called his home run in Game 3.

One of the reasons for the museum is people are seeing something they will never experience.

“When I was on the Coors Field design committee, I thought why not make centerfield like it was at the old Polo Grounds, make it 500 feet away and don’t have your little garden out there, whatever. Baseball will not do that. Baseball can get really stuck in their ways and they’re extremely conservative and don’t like anything ‘radical’ like the old ballparks represented. So I tried to do the next best thing and put it in a museum.”

To Hellerstein’s knowledge no players have made the walk across Blake Street to the museum.

“The problem is that the players of today, most of them could care less about the history of the game. It’s very sad but it is what it is. Today’s ballplayers, the money drives most everything.”

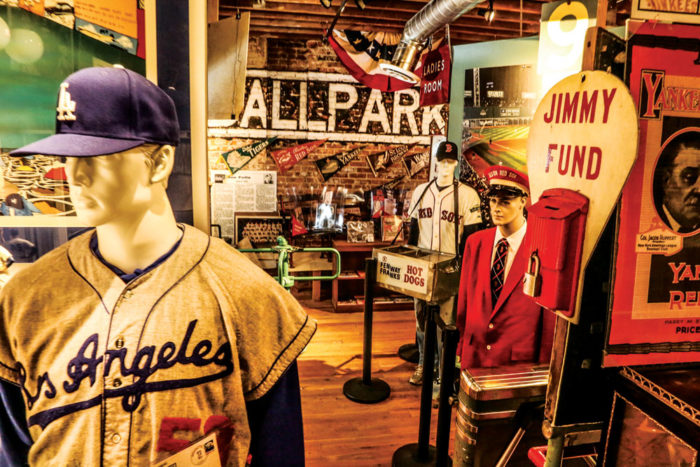

Stadiums, current and former, are the focus of the National Ballpark Museum near Coors Field. Hundreds of photographs, bricks from long-gone parks, turnstiles, signed baseballs, and other memorabilia fill several rooms. Chicago won the National League pennant in 1932, lost to the New York Yankees in the World Series, the one in which Babe Ruth is said to have called his home run in Game 3.Visitors enter Hellerstein’s collection of thousands of bits of baseball history by passing through, not a metal detector, but an actual turnstile used at Shibe Park in Philadelphia in the 1900s. Inside, they’ll find Don Drysdale’s 1961 Los Angeles Dodgers road uniform, an exceedingly rare usher’s cap from Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, dozens of signed balls, and an entire section devoted to the minor-league Denver Bears and Denver Zephyrs, predecessors to the Rockies.

Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, dozens of signed balls, and an entire section devoted to the minor-league Denver Bears and Denver Zephyrs, predecessors to the Rockies.

I was delighted to see an area about Wrigley Field and the Chicago Cubs, where fans can look up at a small reproduction of the ballpark’s famed hand-operated scoreboard, stand on a rubber on-deck circle with the Cubs logo, and sit on a section of actual bleacher seats. There’s even a much-sought-after and

A baseball autographed by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

working Cubs pinball game in one corner.

Ultimately, Hellerstein’s hope is that the museum “conveys my love of baseball and ballparks, the passion, and conveying that this is our national pastime and that it’s the greatest game ever played. They say history repeats itself. It doesn’t. Are we going to have another Mona Lisa? No.”

The National Ballpark Museum, 1940 Blake Street, is open from noon to 4:30pm Tuesdays through Fridays and 11am to 5pm Saturdays. Admission is $10 for adults; children under 12 are free. Call 303.974.5835 for information.

0 Comments