Community members Chris Reed (foreground) and Monica Aldridge persuade a fleeing theater-shooting suspect to drop his gun during a virtual training session at the Denver Police Academy.

Law enforcement may well be the only profession where you can be called upon to change a tire, address neighbors’ disputes over barking dogs, intervene on behalf of someone who has been physically battered by a spouse, and talk down a gunman. All in one day. “Regardless of the purpose of the call,” says Capt. Sylvia Sich, the 38-year Denver Police Department veteran now in charge of the Police Academy, “that is the most important thing happening in that person’s life right now…And you respond to it that way.”

Training

Located in the Central Park neighborhood, the Denver Police Academy is an old airplane hangar that was transformed into the education and training facility for police recruits in 1994. The Academy opened its doors so the Front Porch could learn more about its training in the aftermath of a summer that brought renewed attention to law enforcement reform, funding, and training. Though inadequate training has been cited as a problem in some departments around the country, Sgt. Noel Ikeda, who oversees Academy training, says, “We do more hours of training than what’s required.” With 1018.5 training hours, DPD requires almost double the 556 hours standard for Colorado peace officers before recruits graduate and begin four months of field training with careful oversight, part of a nine-month probationary period.

The Police Academy has a 300-degree small arms training simulator that shows scenarios officers often encounter. Trainers can instruct and replay scenarios as they work with recruits on both verbal de-escalation skills and judgment calls on use of their weapons. The distressed-father-on-the-bridge scenario impelled community member Christine Reed (foreground) to put down her weapon in an attempt to gain the father’s trust and bring the baby to safety. While an officer might holster their weapon in this situation, Sich points out that officers would never put their weapon down.

![]()

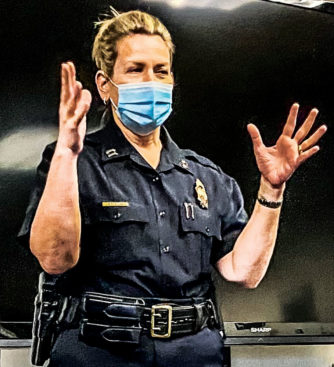

Capt. Sylvia Sich stresses the importance of communication and training for safety in any situation.

All of the officers emphasize the importance of communication and verbal de-escalation in their work. “Our communication skills are paramount,” says Technician Anthony Norman, who is a recruiter for DPD. Recruits learn to engage in “verbal judo” and verbal de-escalation techniques—they are taught to only resort to physical de-escalation when they’ve exhausted their verbal arsenal. “Sometimes de-escalating doesn’t work,” admits Technician Dan Figueroa. “Either the guy isn’t open to that, or maybe I’m just not good enough with my verbal skills.” Figueroa oversees recruits’ training in the VIRTRA, a 300-degree small arms simulator that presents different scenarios law enforcement officers routinely encounter, allowing them to practice their verbal de-escalation skills and a host of other techniques.

Armed with bright blue plastic handguns that fire lasers, Central Park residents Chris Reed and Monica Aldridge try an exercise recruits undertake as part of their training. Standing before the VIRTRA, the two women engage in two immersive scenarios. In one, a father experiencing a mental health crisis holds his infant over the side of a bridge; in another they are called to a theater shooting-in-progress. The VIRTRA allows recruits to partake in what Figueroa refers to as “stress inoculation.” He can run different simulations to challenge recruits’ decision-making skills under pressure and ratchet up the stress as needed to push them to be better officers.

“I was sort of surprised how I reacted,” says Aldridge after the exercise. She felt Figueroa’s guidance really helped her to be calmer and not, for example, shoot at the panicked civilians running from the theater as she entered. Still, when an armed plainclothes police officer suddenly appeared in her peripheral vision, she realized that for a moment she forgot the suspects’ description. She felt the physiological impact of the scenario even after leaving the Academy. “I feel like if there had been a heart rate monitor on me, my heart rate would have been up,” she admits. “Even after I got home I felt like I had some adrenaline from this.”

The instruction in the theater scenario where there were active shooters was “keep your head on a swivel, line your sights up.” Trainers can adapt the scenarios in response to recruits’ behaviors and actions to teach and elicit specific skills.

Reed says that as the pair debriefed on the way home, she realized there were things in the theater scenario she hadn’t picked up on or fully grasped in the moment. “Things were happening so fast. I definitely felt like I was calm and cool and could call on my faculties to de-escalate in the first scenario [with the baby]; I felt far more capable with the mental health issue than taking down an active shooter.”

“A simulation like that would be beneficial for civilians who want to open carry and want to be the good guy; you just don’t know how you’re going to feel when you’re in that situation,” Aldridge says. Figueroa explains that it’s not uncommon in a situation like the theater scenario for people to fire their weapons in response to hearing a shot; this “sympathetic fire” is one variable the Academy works to prepare recruits to avoid.

Sgt. Eric Knutson says the Academy teaches recruits to “crawl, walk and run,” with VIRTRA being the walk. “They get to make mistakes there. We get to stop it, pause it, reset it and redo it. And then the live scenarios that are run, that is our RUN.” DPD conducts live scenarios with actors in a mock apartment setup within the old hangar. “We’re seeing their eyes, we’re reading their body language, and we’re actually getting to that level of understanding,” through the live scenarios, says Knutson. Figueroa says even though recruits do learn how to fire weapons and fight, “first we teach them how not to fight. And that’s where we spend more time.”

Post-Floyd Changes

About a year ago, DPD filmed a scenario for the VIRTRA that anticipated some of the challenges the department faced during this tumultuous summer. In this scenario, a hostile crowd surrounds an officer, and the recruit arriving at the scene has to intervene, not to calm the crowd, but to talk the officer down so the public can continue to exercise its free speech rights. “Our duty-to-intervene training began long before there was a House bill,” Knutson says, referring to the Law Enforcement Integrity Act that the General Assembly passed earlier this year.

With this Act, Colorado made national headlines as one of the first states to take pro-active measures for police reform. The legislation—some of which won’t go into effect until 2023—bans some techniques, mandates body-worn cameras, and creates a statewide database for the use of force, departmental violations and other issues. It also requires that officers “intervene when another officer is using unlawful physical force and requires the intervening officer to file a report.” (https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb20-217) Failure to intervene can result in an officer’s decertification. “We will not tolerate bad apples,” Ikeda says.

The Act bans the carotid choke hold or carotid compressor technique, which Knutson explains “cuts off the blood supply to the brain temporarily.” He says “10 to 15 years ago, we [DPD] had decided that the only time an officer can ever use that is in a deadly force encounter, meaning that the officer could have shot that individual….we still trained it, but you can imagine how often it was used.” Knutson adds that the likelihood that an officer would be in a deadly force encounter and choose to holster their weapon and instead use this technique was always extremely low. Though it was kept in the training repertoire, removing it was “not a big deal.” Knutson says de-escalation techniques have always been central to the training.

DPD has also changed the hand position permitted on other techniques, allowing officers to position a hand on a face, avoiding the neck area entirely. Whenever an officer unholsters their weapon, whether mace, a Taser or a handgun, they must now document that action with a “show of force” report, even if they do not employ the weapon.

“We believe in police reform,” says Ikeda. When asked what has changed in DPD’s training since Floyd’s death, he says “Nothing has changed. Our curriculum is exceptional.” He says he hand-picks trainers and staff to ensure that recruits are learning from the best. Knutson concurs: “We’re in a constant state of evolution—and so police reform is welcomed because it’s something that we’re already doing.”

All of the officers wish the public would recognize that not all who dedicate their lives to service and choose law enforcement are somehow the same. Most who wear the badge do not condone the actions of the minority of bad officers. Many of the officers grew up in Denver, and they name their high schools and neighborhoods with pride. Their stories are as varied as those of the community they serve. “We are the public,” says Figueroa. “We are you.”

Front Porch photos by Christie Gosch

0 Comments